Gender: When the body and brain disagree

Researchers are trying to unravel the tangled roots of gender identity

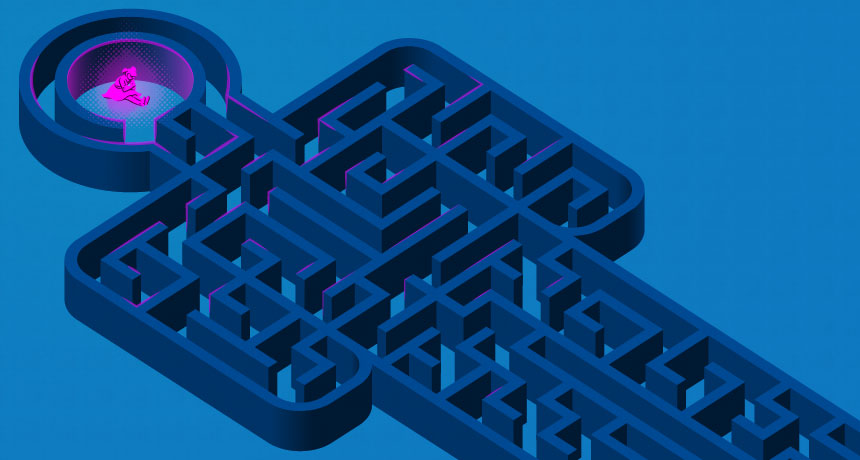

Transgender people often feel they are trapped in a body that does not match the identity that their brain "knows" them to be. For some of these people, getting others to see them as they see themselves can involve navigating a confusing maze that may begin as early as toddlerhood.

Illustration by James Provost

First of two parts

In November 2014, Zoë MacGregor celebrated her 13th birthday. Like any teen might, she invited a friend to her house for a sleepover. They ordered pizza, had brownies and ice cream for dessert, then watched a movie.

The Seattle-native’s journey to becoming a teen had been very different from that of many of her friends, however. Until she was 9, the girl had lived as Ian — a boy.

But by spring 2011, Zoë recalls, “I was starting to feel more and more like I was not quite boy, but sort of both.” Eventually it hit Zoë that she was neither a boy nor a hybrid of two genders. “No,” she realized, “I’m a girl.”

Doctors refer to people who feel that they belong to the opposite sex from the one they were assigned at birth as transgender individuals. (The term comes from the Latin, where trans- means “on the far side.”)

One week before the end of third grade, Zoë announced her social transition at school. In this case, transition described the start of a process to make outward signs of gender match one’s inner identity. For transgender children and youth, this social transition usually involves changing one’s name, hairstyle and choice of clothes.

As a first big step in this process, Zoë reintroduced herself to her classmates. “I didn’t ask them to start calling me Zoë. It was more like I said: ‘Now my name is Zoë.’” Roughly a year later, her parents legally changed her name.

At 13, she now has a hard time recalling what life was like before her transition. But her identification as a girl started much earlier.

Zoë was 4 when she first asked for a dress. Her mom, Carolyn MacGregor, remembers agreeing — hesitantly — but didn’t promise to buy one right away. “It was the third time she asked when I thought, ‘I really need to not put this off.’”

The next day, the two went to a store and picked out a few dresses. Zoë put one on as soon as she got home. Within a few minutes, a sitter arrived to watch Zoë and her younger sister. Before Carolyn knew it, her two kids and the sitter headed out the door to a park. Zoë was still wearing the dress.

“At that moment, I realized it wasn’t just for dress-up. She wanted a dress as part of her clothing,” Carolyn says of Zoë. Looking back, she adds, “It was something [Zoë] quickly integrated into her everyday life. It wasn’t, ‘I’m going to go play dress-up.’ I never felt like it was something that was just a role.”

Today, Zoë is an otherwise typical eighth-grader. The teen loves to read and she plays percussion. At school, her favorite subject is art. She enjoys an after-school club where she plays the popular video game Minecraft.

Outspoken and confident, she says it’s important that people understand that being transgender isn’t really a “choice.” Instead, she explains, “It’s more like a realization that you are that different gender.”

Sex. Gender. What’s the difference?

Although many people use the terms sex and gender interchangeably, they mean quite different things. Indeed, sex and gender don’t necessarily agree. That’s how it is in Zoë’s case.

Gender is based on culturally accepted norms — attitudes or behaviors that are typical for males or females. Gender identity has to do instead with our inner sense of who we are. People often express their gender identity by how they dress or behave.

Meanwhile, sex is determined at conception by the genes each of us inherits from mom and dad. It may become visible by ultrasound several months into pregnancy.

Chromosomes hold genes. They’re the tiny pieces of DNA that tell our cells what to do. Humans have 23 pairs of chromosomes. One pair consists of sex chromosomes. They come in two forms: X’s and Y’s. Women have two X’s. So when they share half of each pair of chromosomes with their offspring, the sex chromosome they offer will always be an X. Men have an X and a Y. So if dad shares an X chromosome with his child, it will make a girl (XX). If he shares a Y chromosome, the child will be male (XY). Or at least, that’s usually the case.

When it comes to sex, researchers have learned that biology can be more complicated than just ‘boy’ or ‘girl.’ For instance, some people carry two X chromosomes mixed with a fragment of a Y chromosome. These people develop into what look to be males. That happens even though the presence of two X chromosomes means that they are female, at least biologically.

It gets even more complicated when gender identity enters the picture. For more than 99 percent of the world’s population, gender identity and biological sex will agree. Such a person is called cisgender. (The Latin prefix cis- means “on the same side.”) But a small share of people experiences a mismatch between sex and gender.

Some of these people grow up feeling like they aren’t the gender the rest of the world — including their parents and doctors — sees them as. This experience is called transgender. The term transgender is distinct from one’s sexual orientation, meaning whether a person is attracted to males or females.

Transgender individuals may outwardly appear male or female. But for reasons that are still unclear, they feel like — and, eventually report knowing themselves to be — the opposite gender. Some may even identify a little bit with both genders.

Untangling sex and gender

During pregnancy, genetic factors influence the development of the embryo as it grows into a fetus. An XX person (girl) usually develops ovaries. An XY person (boy) will usually develop testes. In individuals with XY chromosomes, there is a gene on the arm of the Y chromosome, called SRY. This gene signals the development of testes. When an SRY is not present, an ovary will develop. That will then lead to development of the female anatomy. If testes develop, they will go on to produce the male hormone called testosterone (tess-TOSS-ter-own). This hormone instructs the body to make male genitals. It also leads to the development of bigger bones, a brain structure unique to males and other male physical characteristics.

The basic biology behind how chromosomes and genes signal the body to take on a female or male anatomy has been known for a long time. Still, researchers are learning a great deal about how much more complex this sex determination is than they had originally thought. And researchers know far less about what drives gender.

“To my knowledge, no studies have conclusively demonstrated where our sense of gender identity comes from,” says Kristina Olson. She works at the University of Washington in Seattle.

As a developmental psychologist, Olson studies how people develop and change as they grow from infancy into adulthood. Some people have speculated that genes, the environment or hormone levels might play a role in influencing gender, Olson says. In fact, she says, “I know of no study showing one, the other or which combination makes gender.”

For thousands of years, careful observers — namely, parents — have noticed that children at an early stage begin to strongly express a preference for certain toys, colors and clothing. Around this same early age, children also begin to express their gender identity.

“What we know from typical gender development is that kids generally know and can say whether they’re a boy or a girl around age 2 or 3,” says Olson.

By that same age, many transgender children also will express their gender identity. But in their case, it will differ from the expected, Olson says. “Most people find it shocking that a transgender kid could ‘know’ that they are or are not a particular gender so early,” she says. However, Olson’s research tells her that it makes complete sense that gender identity can show up at the same age in transgender and cisgender children.

To better understand transgender kids

In 2013, Olson and her colleagues launched the TransYouth Project. This long-term national program is studying the development of up to 200 transgender children between the ages of 3 and 12. The goal is to learn how their gender identity develops.

For every transgender child, Olson’s team is including a cisgender child. That second child is called a control. Each pair of participants will be as alike as possible. For instance, if the transgender participant identifies as a boy, the control will be a boy. Both will be the same age. And both will come from families with similar incomes.

When possible, the study also enrolls brothers and sisters. This will allow the researchers to compare how a family’s support and belief systems might affect the siblings.

In an earlier study, Olson and her colleagues found that transgender children as young as 5 identified just as strongly with their expressed gender as cisgender kids did. That study also asked the participants, all aged 5 to 12, to link concepts related to their gender. For example, when given a list of words on a computer screen, someone might pair “me” and “female.” Findings from that study appeared April 5 in Psychological Science.

Some research has suggested that transgender children may simply be confused about their gender identity, or wrong. New data imply this is not the case, Olson and her colleagues say. Nor are transgender children just engaging in imaginative play, her team adds. Boys, for instance, are not simply pretending to be girls, as other children might pretend to be a dinosaur or superhero.

Olson plans to track kids taking part in the TransYouth Project through at least puberty — and, if funding continues, into adulthood. Along the way, her team’s data should uncover much about how transgender youth find their way through important stages in their development, from puberty to parenthood.

Few good long-term data exist on transgender children, Olson says. That’s especially true for those who are fully supported by their family and community in expressing their identity. To fill in those missing data, Olson explains, “is a huge part of why I’m doing this study.”

A complicated soup

Researchers know little about how transgender people differ in their biological development, if at all, from cisgender individuals. Nor, as mentioned earlier, do scientists know where our sense of gender comes from. Studies of children who have been allowed to transition to the opposite gender are providing clues.

As it turns out, the brain appears to play a bigger role in our identity than does anything else, says William Reiner. He is a child and adolescent psychiatrist. He works at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center in Oklahoma City. Reiner studies young children and teens who transition to the opposite gender of what doctors had assigned them at birth (based on their apparent biological sex). Some of these children are transgender. Others may have experienced conditions in the womb that led their genitals to develop abnormally (see explainer below).

This second situation can lead doctors to incorrectly interpret an individual’s biological sex. (This condition should not, however, be confused with transgender identity). If a boy is born with the genitals of a girl, for instance, a doctor may by accident assign the child to the wrong sex. As this boy grows up, his parents and doctor may realize the mistake. But just telling this child that he’s a girl won’t convince him that this is who he is. That’s because identity is determined internally, within the complex interactions among the 100 billion cells in his brain.

The brain is a complicated soup of chemicals, Reiner points out. Somehow, he says, these chemicals add up to something whose “total is much larger than the sum of its parts.” Part of that sum is who we see ourselves as. Our identity. “And part of that,” he adds, “is whether we’re male and female.” The gender assigned to a newborn is based on what that baby’s body looks like. Yet that outward identity, while important, “is not the only part,” he says.

By looking at someone’s body, or even mapping that person’s genes, “We can’t really answer the question of what identity is.” That, he says, remains hidden within the inner workings of our brain.

A wide spectrum in animals

Transgenderism is unique to humans. Yet research has turned up lots of variety within the sexual development and behavior of animals. Like people, animals exhibit behaviors typical of males and females. Still, many social and other behaviors in animals do not fit neatly into those categories, notes Paul Vasey. He works at the University of Lethbridge in Alberta, Canada. As a comparative psychologist, he studies how behaviors in humans and animals differ or appear the same.

With such a wide range of differences in sexual development and behaviors in the animal kingdom (see Explainer: Male-female plasticity in animals), Vasey says that it’s not surprising to see similar variation among people too. “There’s a continuum,” he concludes “— in both the animal kingdom and in humans.”

Next week: Identifying as a different gender

Power Words

(for more about Power Words, click here)

adrenal gland Hormone-producing glands that sit at the top of the kidneys.

androgen A family of powerful male sex hormones.

chromosome A single threadlike piece of coiled DNA found in a cell’s nucleus. A chromosome is generally X-shaped in animals and plants. Some segments of DNA in a chromosome are genes. Other segments of DNA in a chromosome are landing pads for proteins. The function of other segments of DNA in chromosomes is still not fully understood by scientists.

conception The moment when an egg and sperm cell fuse, triggering the development of a new individual.

congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) A genetic disorder of the adrenal glands.

control A part of an experiment where there is no change from normal conditions. The control is essential to scientific experiments. It shows that any new effect is likely due only to the part of the test that a researcher has altered. For example, if scientists were testing different types of fertilizer in a garden, they would want one section of it to remain unfertilized, as the control. Its area would show how plants in this garden grow under normal conditions. And that give scientists something against which they can compare their experimental data.

dihydrotestosterone (DHT) A male sex hormone, or androgen, that plays an important role in the development of male physical characteristics and reproductive anatomy.

enzymes Molecules made by living things to speed up chemical reactions.

feminize (in biology) For a male person or animal to take on physical, behavioral or physiological traits considered typical of females.

fetus (adj. fetal) The term for a mammal during its later-stages of development in the womb. For humans, this term is usually applied after the eighth week of development.

gender The attitudes, feelings, and behaviors that a given culture associates with a person’s biological sex. Behavior that is compatible with cultural expectations is referred to as being the norm. Behaviors that are incompatible with these expectations are described as non-conforming.

gender identity A person’s innate sense of being male or female. While it is most common for a person’s gender identity to align with their biological sex, this is not always the case. A person’s gender identity can be different from their biological sex.

gender-nonconforming Behaviors and interests that fall outside of what is considered typical for a child or adult’s assigned biological sex.

genitals/genitalia The visible sex organs.

hormone (in zoology and medicine) A chemical produced in a gland and then carried in the bloodstream to another part of the body. Hormones control many important body activities, such as growth. Hormones act by triggering or regulating chemical reactions in the body.

intersex Animals or humans that display characteristics of both male and female reproductive anatomy.

masculinize (in biology) For a female person or animal to take on physical, behavioral or physiological traits considered typical of males.

neuron Any of the impulse-conducting cells that make up the brain, spinal column and nervous system. These specialized cells transmit information to other neurons in the form of electrical signals.

norms The attitudes, behaviors or achievements that are considered normal or conventional within a society (or segment of society — such as teens) at the present time.

ovary (plural: ovaries) The organ in the females of many species that produce eggs.

psychology The study of the human mind, especially in relation to actions and behavior. Scientists and mental-health professionals who work in this field are known as psychologists.

sex A person’s biological status, typically categorized as male, female, or intersex (i.e., atypical combinations of features that usually distinguish male from female). There are a number of indicators of biological sex, including sex chromosomes, gonads, internal reproductive organs, and external genitalia.

sex chromosomes These are the chromosomes that contain genes to establish an individual’s sex: male or female. In humans, sex chromosomes can be either X or Y. People get one chromosome from each parent. Two X chromosomes will make the offspring female (like her mom). An X and Y will make the child male, like his dad.

sibling A brother or sister.

testis (plural: testes) The organ in the males of many species that makes sperm, the reproductive cells that fertilize eggs. This organ also is the primary site that makes testosterone, the primary male sex hormone.

testosterone Although known as male sex hormone, females make this reproductive hormone as well (generally in smaller quantities). It gets its name from a combination of testis (the primary organ that makes it in males) and sterol, a term for some hormones. High concentrations of this hormone contribute to the greater size, musculature and aggressiveness typical of the males in many species (including humans).

transgender Someone who has a gender identity that does not match the sex they were assigned at birth.

womb Another name for the uterus, the organ in which a fetus grows and matures in preparation for birth.

Word Find (click here to enlarge for printing)