How to Fly Like a Bat

Everyone knows that bats aren't birds, but it turns out that they don't even fly the same way.

By Emily Sohn

It takes weeks, treats, and a lot of patience to train a bat to fly inside a wind tunnel. Bats already know how to fly, of course. The problem is to get them to do it inside a small tunnel with the wind rushing at them.

So scientists at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, use rewards to coax the animals. If the bats land on the floor or walls of the wind tunnel and refuse to fly, the scientists move them to an enclosure without food. But “if they fly for a minute without crashing, we feed them,” says Sharon Swartz, a biologist at Brown.

The bats soon learn that to get a treat, they have to fly.

|

|

This bat has learned to fly in a wind tunnel, where scientists filmed its motions. |

| Arnold Song |

After weeks of training, the bats learn to fly in place inside the wind tunnel, like a person who can walk or run without falling off a moving treadmill.

Bats on film

Swartz and her colleagues then use high-speed video cameras to film the animals in motion. The work is revealing surprising details about how bats fly.

When they first looked at the images, scientists were stunned to see the complexity of the bats’ movements, especially when compared with those of birds. The work “has really challenged long-held beliefs about how we think about bat flight,” says Betsy Dumont, a biologist at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst.

|

|

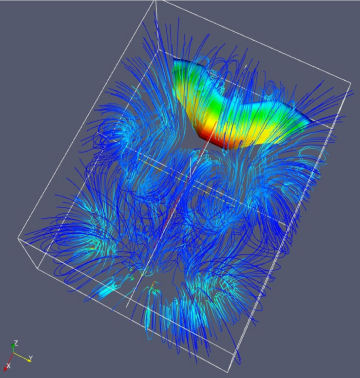

This computer-generated image shows how a bat’s flight alters the flow of the air in the wind tunnel. The blue lines behind the bat (which appears to be multicolored) are streamlines that show how the animal’s motions have disturbed the air. |

| David Willis and Misha Kostonadov |

A better understanding how bats fly, researchers hope, will help them design small flying machines that can move and change direction quickly like bats do. The United States Air Force is so interested in developing batlike aircraft that they’re funding the research.

Fast bat facts

There are about 1,200 species of bats in the world, Swartz says. Some eat fruit. Others eat insects or nectar. And just a few drink blood.

Some bats use their eyes to see where things are. Others collect information about their surroundings by bouncing sound off objects and listening to the echoes.

But what all bats have in common (other than being the only flying mammals in existence) are flexible wings that enable them to change directions quickly. If you’ve ever seen bats darting through the air at dusk, you probably noticed how abruptly they can change directions.

|

|

Bats flit about in the night. Their versatile wings enable them to maneuver. |

| iStockphoto |

Scientists have long assumed that bats fly the same way as birds and insects do—with rigid, airplanelike wings that hinge at the shoulder. The problem with that assumption, however, is that bats aren’t birds or insects. As mammals, they have more in common with people, horses, and dogs than with other flying creatures.

|

|

Ducks and other birds fly using rigid wings that hinge at the shoulder. Bats use a different technique to stay airborne. |

| iStockphoto |

For example, birds have hollow bones, and insects have no bones at all. But most mammals have solid, heavy bones, which would make flying tough.

To solve this problem, bats have evolved strong, heavy bones near their shoulders, where they need more support. They’ve also saved some weight by developing lighter, weaker bones near the tips of their wings. The result is a light, but strong, and very flexible, wing.

Bat wings

Bats flap their wings very quickly, so scientists must use extremely fast cameras to study these animals in flight. This type of technology has only recently become available and affordable.

“In the past, if you wanted to get 1,000 frames a second, you would need so much light you would probably burn the bat,” Swartz says. “Now, we have cameras that are able to take lots of images with relatively little light.”

Swartz studies a bat called the dog-faced fruit bat. An adult weighs about 1 ounce and measures about 11 inches across from wingtip to wingtip.

Before filming, the researchers put 54 white dots all over the bat’s wings. Then, they put the bat into a wind tunnel that is about 50 inches long and about 50 inches wide.

|

|

In a wind tunnel, a powerful fan at one end blows a steady breeze toward the other end. Bats can fly against the wind while staying in front of cameras that record their wing movements. |

| iStockphoto |

As the bat flies, three high-speed cameras capture the animal’s movements from different angles. A computer program then processes the movements of the white dots on the wings to produce a three-dimensional virtual bat. In slow motion, the virtual bat reveals exactly how its wings move every fraction of a second during flight.

The first time that Swartz saw the results, she was amazed.

|

|

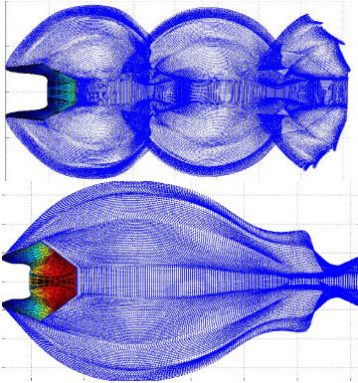

Computer simulations show how air flows around a bat’s wing while the animal is flying slowly (top image; at about 7 miles per hour) and more quickly (bottom; at about 16 miles per hour). |

| David Willis |

“The motion of these bat wings is just gorgeous,” she says. “It’s like a dancer. It’s fabulous.”

Swartz was also surprised to see how complicated the wings’ motions are during flight. The wings curve and change shape constantly as the animal flies, but they never flatten like airplane wings. That shows that even if airplanes flapped their wings, they wouldn’t be flying the same way as bats do.

On the down stroke, one wing sometimes even covers the other for a fraction of a second. “It’s as if the bat were about to fold up and go to sleep,” Swartz says. “You wouldn’t expect that if you believed the flapping-airplane model.”

A real bat mobile?

Before bat ancestors developed wings more than 80 million years ago, the animals had arms and grasping fingers. As bats evolved, their bodies changed to make flight possible. Bats today still have elbow joints and individual finger bones hidden inside their wings, but they only use them to adjust the shape of their wings.

Bats have become excellent flyers, Dumont says. “Just think about these animals flying around at night at a decent speed and maneuvering around objects,” she says. “It’s spectacular.”

Engineers would like to design vehicles that fly the way bats do. The military could use small, unmanned aircraft that maneuver through war zones without attracting attention. Tiny, batlike flying machines that could make tight turns in small spaces would also be helpful during emergencies, such as fires, earthquakes, or volcanic eruptions, to rescue people from tight, collapsed spaces or perform other tasks.

Bats are small and can maneuver well in small spaces. Despite their sometimes mysterious and elusive nature, there is a lot we can learn from them.

Going Deeper: