Piranhas and plant-eating kin replace half their teeth at once

This tooth-swapping strategy probably helps keep the fishes’ chompers sharp

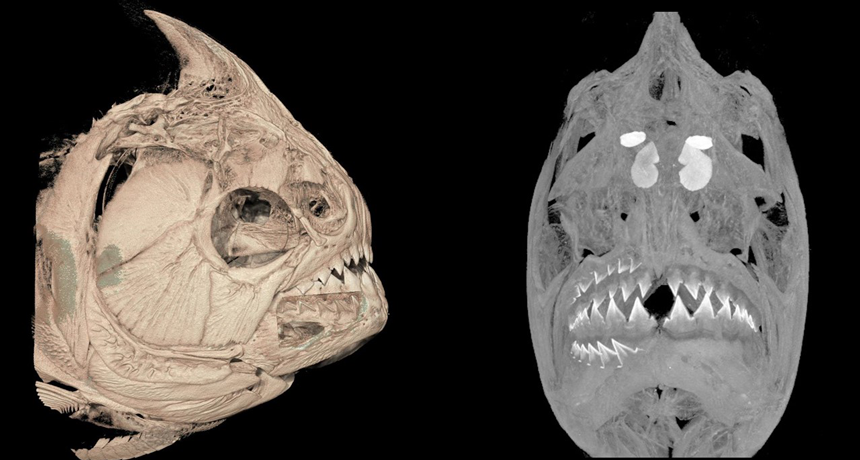

Piranhas (one shown in this CT image) and their close relatives, pacus, store rows of extra teeth in their jaws. A new study shows how the fish lose and regrow all the teeth on one side of the mouth at a time.

M. KOLMANN/GWU

If the tooth fairy collected piranha teeth, she’d have to part with a lot of money on every visit. That’s because these fish lose half of their teeth at once. Each side of the mouth takes turns shedding and growing new teeth. Scientists had thought that this tooth swapping was linked to the piranhas’ meaty diet. Now, research shows that their plant-eating relatives do it too.

Piranhas and their cousins, the pacus, live in the rivers of South America’s Amazon rainforest. Some piranha species gobble up other fish whole. Others eat just fish scales or fins. Some piranhas may even feast on both plants and meat. In contrast, their cousins the pacus are vegetarians. They feed on flowers, fruit, seeds, leaves and nuts.

While their dining preferences differ, both types of fish share weird, mammal-like teeth, reports Matthew Kolmann. An ichthyologist (Ik-THEE-ah-luh-jizt), or fish biologist, he looks at how fish bodies differ across species. He works at George Washington University in Washington, D.C. His team now sheds light on how these Amazonian fish swap out their teeth.

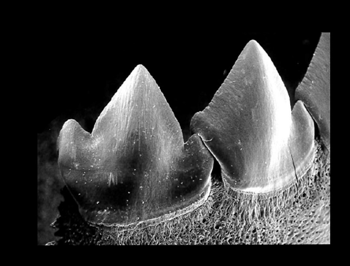

Eating such different things suggests that dietary choices are not why piranhas and pacus shed so many teeth at once. Instead, this tactic may help the fish keep their teeth sharp. Those teeth “do a lot of work,” says Karly Cohen. A member of Kolmann’s team, she works at the University of Washington in Friday Harbor. There, she studies how the shape of body parts relates to their function. Whether snatching chunks of flesh or cracking nuts, she says, it’s important that the teeth be “as sharp as possible.”

The trait likely first popped up in a plant-eating ancestor that piranhas and pacus share, the team suggests. The scientists described their findings in the September issue of Evolution & Development.

A team of teeth

Piranhas and pacus keep a second set of teeth in their jaws like human kids do, Cohen says. But “unlike humans that replace their teeth only once throughout their life, [these fish] do this continuously,” she notes.

To look closely at the fishes’ jaws, the researchers performed CT scans. These use X-rays to make a 3-D image of a specimen’s insides. In all, the team scanned 40 species of preserved piranhas and pacus from museum collections. Both types of fish had extra teeth in the upper and lower jaws on one side of their mouths, these scans showed.

The team also cut thin slices from the jaws of a few wild-caught pacus and piranhas. Staining the bones with chemicals uncovered that both sides of the fishes’ mouths held teeth in the making. What’s more, teeth on one side were always less developed than the other, they found.

The jaw slices also showed how piranha teeth link together to make a saw blade. Each tooth has a peg-like structure that hooks into a groove on the next tooth. Almost all the pacu species had teeth that locked together. When these linked teeth were ready to drop, they fell out together.

It’s risky to shed a group of teeth, says Gareth Fraser at the University of Florida in Gainesville. He’s an evolutionary developmental biologist who was not part of the study. To explore how different organisms evolved, he studies how they grow. “If you replace all your teeth at once, then you’re basically gummy,” he observes. These fish get away with that, he thinks, because there’s a new set ready to go.

Each tooth has an important task and is like “a worker on an assembly line,” Kolmann says. The teeth may latch together so they work as a team, he says. It also prevents fish from losing just one tooth, which could make the whole set less effective.

Though pacus’ and piranhas’ teeth develop in a similar way, what those teeth look like can vary a lot across these species. The scientists are now looking at how the shape of the fishes’ teeth and skull may relate to how their diets have evolved over time.