Study appears to rule out volcanic burps as causing dino die-offs

When toxic gases would have been spewed does not match when extinctions occurred

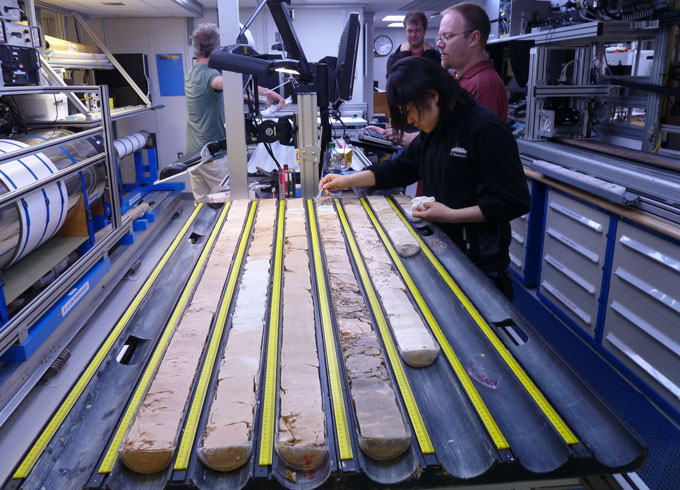

About 66 million years ago, volcanic eruptions blanketed in lava much of India’s Western Ghats mountains (some of which appear here). The toxic gases spewed by the eruptions probably were not what killed the dinosaurs.

ePhotocorp/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Volcano burps do not appear to have killed off the dinosaurs. That’s the finding of a new study.

Pincelli Hull led the new work. She studies the history of the oceans at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

Most scientists now concede that an asteroid collided with Earth 66 million years ago, wreaking global havoc to the climate. It slammed into the Gulf of Mexico near what’s now the Mexican town of Chicxulub (CHEEK-shuh-loob). That event marked the end of the Age of Dinosaurs. And dinosaurs weren’t the only casualties. Earth experienced a massive extinction event. In all, about three in every four living plant and animal species disappeared forever.

Some scientists thought another geologic event helped seal the fate of these species. It was a massive, long-term eruption of volcanoes at a site in what is now western India. That site is known as the Deccan Traps.

Hull and her team wanted to see if they could tease out what role, if any, those Deccan eruptions played in the dino die-off.

To do that, she and her team looked at data on temperatures near the time that the dinosaurs vanished. The team also used computers to model how carbon moves through the ocean. The results revealed that volcanic gases could not have brought down the dinosaurs.

Soil deposits suggest the asteroid strike at Chicxulub happened around the same time as the extinction event. Hull’s group now concludes that the giant asteroid impact was the dino killer.

She and her team described the data to support that January 17 in Science.

A truly massive period of eruptions

There were volcanic eruptions within a million years of the extinction event. But around the same time, volcanoes at the Deccan Traps had been quite active. They spewed as much as 500,000 cubic kilometers (120 cubic miles) of lava across the land!

Exactly when this lava spewed out and about, however, had been uncertain. That’s why it has been hard to tell whether the asteroid or volcanoes were most responsible for the die-offs.

Core clues

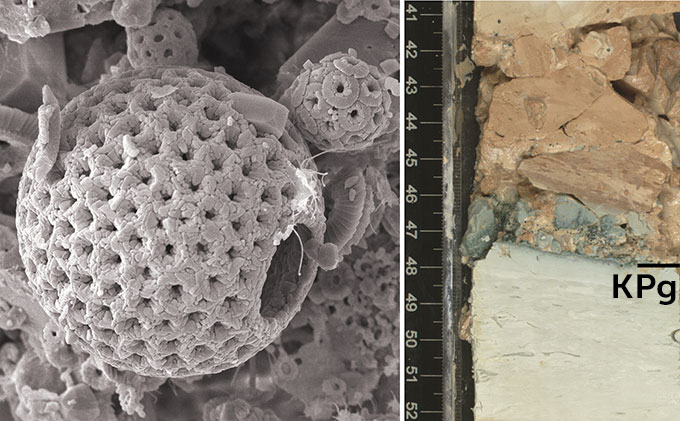

Researchers collected soil from the ocean floor. The soil had material that dates to the mass extinction event 66 million years ago. The team used the soil to pin down when the volcanoes released their potentially deadly gases.

In the past, scientists had used a technique to identify the age of the rocks in the Deccan Traps. They’ve looked at zircon crystals embedded within ash layers that separated flows of lava. They also looked at outcrops of rocks that the lava left behind. Using these data, scientists came up with different dates for the eruptions. Some dates were before the extinction. Others were after.

There’s a hitch with using the rocks, though. Lava would not have been what killed the dinos and other species. It would have been gases spewed by the volcanoes. The carbon dioxide they released would have heated the planet. That could have imperiled life. The volcanoes’ sulfur dioxide emissions also could have acidified the oceans, killing life there. “It’s the outgassing that’s important,” Hull says. But when that occurred, she notes, has been really hard to pin down.

What’s more, huge bursts of carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide could have come either from the asteroid impact or from the eruptions.

Pinning down when the Deccan Traps burped out their toxic gases would help solve the extinction debate. To find that date, Hull and her colleagues looked to the ocean floor.

Deep sea reveals Earth’s dino-era temps

Seafloor sediment holds hints of past temperatures. Using these data, the team created a history of global temperatures over time. That timeline spanned several hundred thousand years. Hull’s group determined the temperatures before, during and after the extinction event. They also considered five different scenarios for when the Deccan Traps might have erupted. Then the scientists compared the scenarios with their new temperature timeline.

Only two of those scenarios matched the temperatures on their timeline.

In one, most of the eruptions occurred several hundred thousand years before what scientists call the Cretaceous (K)-Paleogene (Pg) boundary. This K-Pg boundary is a layer in sediment found the world over. Material below it comes from the Cretaceous Period — the time of dinosaurs. The material above it, laid down later, comes from the Paleogene. It’s the era that marked the rise of mammals. If the Deccan Traps eruptions happened several hundred thousand years before the K-Pg, the planet would have experienced a blip of intense warming. But that blip also would have been over long before the actual die-offs took place.

In the second scenario, half of the eruptions occurred before the K-Pg. The other half happened afterward. Those that happened after the K-Pg could not have caused the extinctions. And the temperature data suggested that any climate-altering impact immediately after the K-Pg would have been limited.

Limited by what? That would be shifts in the ocean carbon cycle, Hull’s team says.

Carbon cycle changes

Some ocean-dwelling plankton (left) build their shells out of a compound called calcium carbonate. There were a lot of these so-called calcareous plankton between 150 million and 66 million years ago. A mass extinction event nearly wiped out these shell-builders. Relics of those creatures (right) were trapped in the ocean sediment. They turned up in samples researchers removed from the ocean floor. The plankton are white and chalky in the older soil (bottom). They are brown in the sediment after the extinction event. The KPg marks the boundary between when the mass die-off happened and after it happened. The researchers think the plankton died off before some of the volcanic eruptions. If so, there would have been lots of calcium carbonate in the ocean water. As a result, the ocean could have absorbed lots of carbon dioxide emitted by the volcanic eruptions. That absorption might have limited temperature impacts of the volcanic emissions and also reduced their acidification of seawater.

Certain tiny, floating ocean creatures build protective shells out of a compound called calcium carbonate. Called calcareous (Kal-KAIR-ee-us) plankton, these creatures became especially abundant about 145 million years ago. And they were everywhere throughout the seas. These plankton using calcium carbonate dissolved in seawater to make their shells. When they die, the plankton and their shells sink to the seafloor. The sinking shells moved half of the ocean’s carbon from its surface to seafloor. That kept the carbon cycle, well, cycling. And that’s what would have happened during the time of the dinosaurs.

Ruling out volcanic eruptions

The temperature data that Hull’s group assembled show that there wasn’t a big increase in temperatures right after the extinction event. But in the second scenario, a lot of large eruptions after the K-Pg would have emitted a lot of carbon dioxide (CO2). And that should have warmed the planet because of acidifying effects of that CO2 in the ocean.

Ocean acidification happens when the ocean absorbs excess CO2 from the air. Calcium carbonate is a powerful buffer against ocean acidification. It neutralizes some of the acid. But when it does that, there is less calcium carbonate available for the plankton to use in building their shells. One result: More carbon stays near the ocean surface instead of becoming shells that will eventually fall to the sediment (and over time get buried).

So even if the volcanoes emitted a lot of CO2 after the extinction, the oceans probably neutralized a lot of it. And that would have limited the ability of volcanic gases to warm global temperatures.

In the end, Hull’s group found, neither eruption scenario matches the temperature data. So neither could have actually caused the mass extinction right at the K-Pg, Hull says. The timing is just wrong.

The new study “used really unique methods” to determine what caused the mass-extinction event, says Courtney Sprain. She is a geoscientist at the University of Florida in Gainesville. What’s more, she says, conclusions in the new study about the timing of the outgassing “make sense.”

That doesn’t necessarily mean the other methods to date the lava were wrong. In fact, the dates of the Deccan Traps lava flows may be correct, Sprain says. There have been a lot of technological advances. Some of those made high-precision dating of the Deccan Traps possible. They also were the ones responsible for revealing something critical about the volcanoes — a potential delay between lava flows and outgassing, she says.

Understanding why there might be a timing difference between lava and gas bursts is an active area of study in volcano research, she says. “There are still quite a few questions about how any volcanic system erupts.”