COVID-19: When will it be safe to go out again?

People want to know when the pandemic — and social distancing — will end

With a pandemic raging, people across the globe have been asked to work or study from home. But many are getting stir-crazy and asking when they can socialize in person.

VioletaStoimenova/iStock/Getty Images Plus

As COVID-19 sweeps across the globe, everyone seems to be asking: When will the coronavirus pandemic — and social distancing — end?

The disappointing answer: No one knows for sure. Here’s what we do know about when it may be safe to come out of our homes and resume normal life.

It will almost certainly take herd immunity to end the pandemic.

Most experts say it’s now too late to contain the virus. That’s what nations were able to manage with two earlier, related diseases — SARS and MERS. That means that like the flu, COVID-19 is likely here to stay, returning in some form year after year. And the current pandemic? That will end only with “herd immunity.”

Herd immunity describes what happens when a large share of the population has become immune to a disease. Because so few people at that point can get infected, the germ finds a hard time finding a new host. How many people must get sick and recover for this to happen depends on how infectious a disease is. This is defined by the particular germ’s basic reproduction number. It’s known as R0 (pronounced R naught).

When a brand new virus emerges, no one is immune. A virus that can be spread easily — such as by a cough, handshake or touching a door handle — can spread like wildfire. And the coronavirus behind the current pandemic is just such a virus.

But once enough people are immune, the virus will hit COVID-19 survivors. They will serve as walls of immunity. As they can’t become re-infected (at least not quickly), the pandemic will start to burn out instead of raging ahead. Scientists call that share of people needed to form such a wall the herd-immunity threshold.

For COVID-19, that threshold may be two out of every three people.

Current estimates put the R0 for the new coronavirus at between two and three. That means anyone with COVID-19 tends, on average, to infect two or three more people. In fact, this number can change based on our behavior. Do most people quarantine themselves before the virus arrives? Or do people continue congregating at concerts, parties, sporting events and religious centers? Do sick people wear masks? Do healthy people protect themselves from contaminated surfaces by washing their hands a lot? Do they wear gloves when they go out of the house?

How — and how much — people interact can make a big difference in that R0.

For the new pandemic, researchers now estimate that the herd-immunity threshold will be between one-third and two-thirds of any given population. Worldwide, that could come to between 2.5 billion and 5 billion people!

Scientists aren’t yet sure how long people infected with COVID-19 remain immune. For now, their best guess comes from one small study. Researchers infected rhesus macaques with the virus. Once the monkeys got well, they could not be reinfected, at least for the next month. A research team in Beijing, China described its findings on that March 14 at bioRxiv.org.

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

Letting the virus burn through the population would be the fastest approach.

People acquire immunity against a virus in two ways: recovering from an infection or getting a vaccine.

Our bodies make antibodies while fighting off a virus. Depending on the virus, those antibodies can linger in the blood for weeks, months — even decades. The next time the body sees the same virus, those antibodies can kill it off. The bad news: You have to suffer through an infection for this to happen.

A vaccination also causes the body to make those protective antibodies. The vaccine fools the body into thinking it had been invaded by the virus. The bad news here: A vaccine against COVID-19 appears to be at least 12 to 18 months away.

That means that the fastest way to herd immunity would be the old-fashioned way: Let the virus burn through a population without fighting it. A March 16 report by researchers in England at Imperial College London used a computer to model that scenario. And without attempts to stop the virus in the United States, the model calculated, the pandemic could peak in about three months.

The costs of such quick herd immunity, however, would be horrific. Roughly four in every five people throughout the United States might get infected, the model estimated. And more than 2 million of the sickened Americans, it said, could die from the virus alone.

The role of models

Before you panic at those huge numbers, keep in mind that a computer model offers only an educated guess about what might happen. It is based on the data fed into it. Such models often are revised again and again, as new numbers come in or as new insights emerge.

Over time, those predictions will be challenged and tested.

Some people are already doing that, notes Deborah Birx. She is a doctor who works for the U.S. State Department. She specializes in infectious diseases. She also works on a new White House Coronavirus Task Force.

When the London model’s numbers first came out, Birx noted they were worrisome. She said they helped justify a recommendation that Americans undertake widespread social distancing. And people keeping their distance is still wise, she said at a March 26 White House briefing for reporters.

But the model’s estimates were meant to be a worst-case scenario. That means they modeled what the researchers thought could happen if society took no action to stop the spread of the disease. In fact, countries around the world are taking action. Chief among those actions: social distancing.

Imagining worst-case scenarios are useful. They help governments plan for what might happen. Models tend to be revised again and again as new numbers come in or as we learn more about a virus and how it spreads.

And Birx noted that experts are collecting more data. Those data would be used to test how behaviors used by the model match up with how people are behaving (such as staying home while the virus is spreading most actively).

Quicker herd immunity would make conditions harder for doctors.

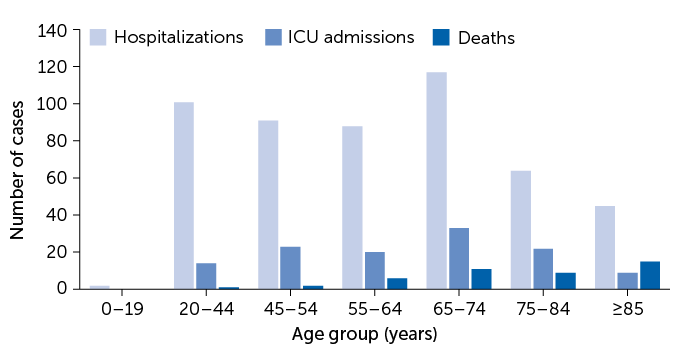

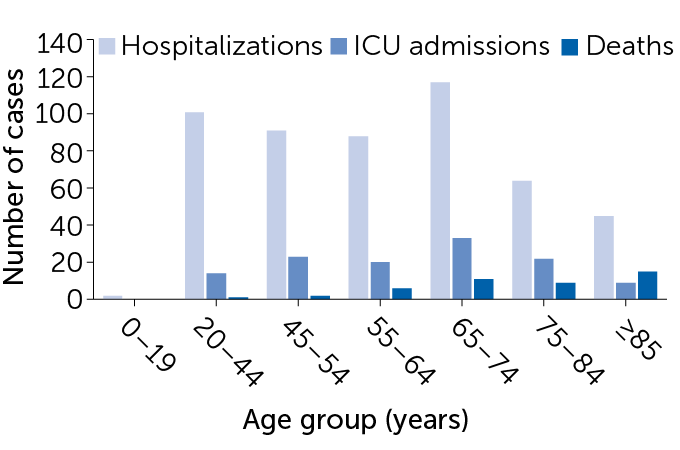

The new virus has been hitting the elderly and those with underlying disease hardest. But younger people, too, can experience severe illness. That’s a point made in a new report by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (see table below).

It looked at the severity of illness in 2,449 Americans from mid-February to mid-March 2020. The share of those who were hospitalized went up with age, it found. Almost one-third of hospitalized patients were at least 85 years old.

But even 2 to 3 percent of infected children and teens were hospitalized. Kids with asthma and other underlying health conditions could face a higher risk of severe disease than others their age. Clearly, all age groups can be harmed by the new scourge.

A Pediatrics paper by a team in China brought that home. Published online March 16, it followed the health of 2,143 children — babies to teens — who fell ill with the virus. Overall, 5 percent developed severe disease, it reported. Among them, 33 “had critical disease.” Many children had extreme trouble breathing. A few needed oxygen or ventilators to help as their bodies fought the virus. One 14-year-old boy even died.

Almost anyone can fall ill

More than half of admissions to intensive care units (ICUs) and deaths reported among U.S. COVID-19 cases between February 12 to March 16 occurred in people 65 or older. But some younger adults also experienced severe disease, a new analysis by the U.S. CDC found. Among hospitalized adults, 1 in 5 were 20 to 44 years old. So were 12 percent of those admitted to an ICU.

Severe outcomes of U.S. COVID-19 cases by age

The pandemic could also limit the effectiveness of U.S. hospitals. Overwhelmed doctors and hospitals might not get to non-COVID-19 cases that also need prompt care. These could include victims of auto accidents, appendicitis patients, cancer cases needing surgery or pregnant women with difficult deliveries.

The ability of some U.S. hospitals to provide critical care to all of the very sick might be lost as early as the second week of April, the Imperial College London report predicted. Hospitals in some big U.S. cities now report infection rates that support this. While there is much still unknown about the virus, most experts agree with this overall picture.

That’s why countries around the world have focused on social distancing. They are trying to slow the surge in new cases and lessen the strain on hospitals.

Social distancing delays herd immunity.

The flipside of successful social distancing is that it slows the pace at which herd immunity develops, notes Michael Mina. He’s an epidemiologist at the T.H. Chan School of Public Health. It’s part of Harvard University in Boston, Mass. Even if extreme social distancing prevents a surge in the coming weeks, he says, the virus could reemerge as soon restrictions are lifted.

“In the absence of robust herd immunity at the population level,” he says, “we have some risk of a second wave of the epidemic.”

Social distancing will need to last up to 3 months, maybe longer.

Society could keep a lid on such a re-emergence by keeping up their social distancing. The Trump administration on March 16 called for significant social distancing to last 15 days. But most experts expect that’s not nearly long enough. Experts have begun arguing that this distancing will need to last one to three months, at least, in the United States to keep hospitals from being overwhelmed.

Hospitals could get a big break if spread of the new virus slows with warmer weather. But for now, there are no sure signs that will happen.

A summer break in cases “would be a great stroke of luck,” says Maciej Boni. He’s an epidemiologist at Penn State University in University Park. If that happened, it might allow more people to return to work or school once the number of new cases begins to fall.

Keeping schools closed and encouraging people to generally stay home could suppress the pandemic after five months, according to early numbers from the Imperial College London model. But once such restrictions are lifted the virus would likely come roaring back, it added.

Until a vaccine becomes available, potentially in 12 to 18 months, a report on the model argues that major social distancing measures will be needed.

Such drastic changes to daily life may be difficult to sustain, Boni admits. “It’s like you’re holding back a wave of infections with Saran Wrap.” However, experts note, boredom and feeling cooped up is far better than taking a risk of getting sick.

Wider diagnostic testing could ease the need for extensive social distancing.

Whether strict isolation could be maintained for months on end is unknown. “We’ve never faced anything like this before,” points out Caitlin Rivers. She’s an epidemiologist at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore, Md.

“I’m not ready to give up on the lessons from places like South Korea and Taiwan,” Rivers says. “They’ve shown the virus can be [locally] contained.” She notes that those places did extensive social distancing. And they coupled that with extensive virus testing. They also isolated infected people and tracked down everyone they had been in contact with.

South Korea, for instance, reported its highest number of new cases, 909, on February 29. Since then, the number has steadily dropped. On March 24, only 76 new cases were reported.

While the United States is ramping up its testing, the virus has spread undetected across the country. Until testing increases by a lot, the only tool the United States has to slow spreading of the virus is wide social distancing.

The reason: Data indicate the pandemic is being driven largely by people who don’t know they’re sick. Some of those data come from a March 16 study in Science. Its international team of authors concluded that 80 percent of new cases in China seemed to have come from people who did not know they were ill.

A big unknown: Are all these efforts something we can keep up?

Right now, there are still too many unknowns to know how — and when — any particular population will attain protective herd immunity. In the coming weeks, disease-trackers will be closely watching the number of new U.S. cases as well as the total number of tests. This may give a good sense of whether social distancing is working in a particular place.

“It’s been amazing to see the swing in society over the past week,” Mina said on March 17. “Nearly everyone has gotten on board.” But he worries about how well people can keep up such strict measures as the weeks wear on. “Societal forces may end up overwhelming the science.”