Ancient recipes helped scientists resurrect a long-lost blue hue

Unmasking this color’s identity took a mix of medieval knowledge and modern science

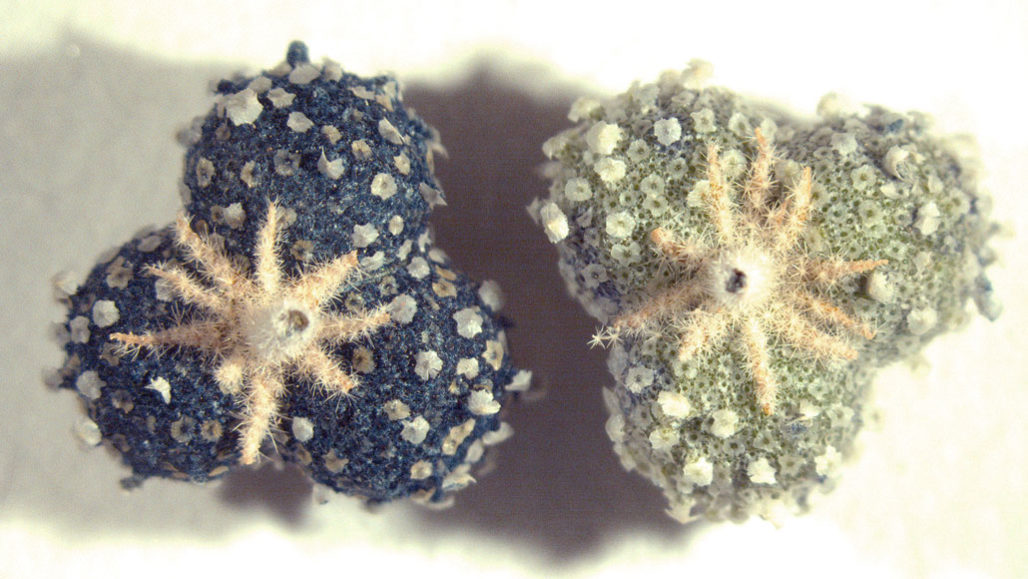

Medieval recipes instructed scientists to prepare the blue watercolor from this fruit of the plant Chrozophora tinctoria. It yielded enough dye to reveal its chemical structure using a suite of lab techniques.

Paula Nabais/NOVA Univ.

Scientists have resurrected a purple-blue hue that had been lost to time.

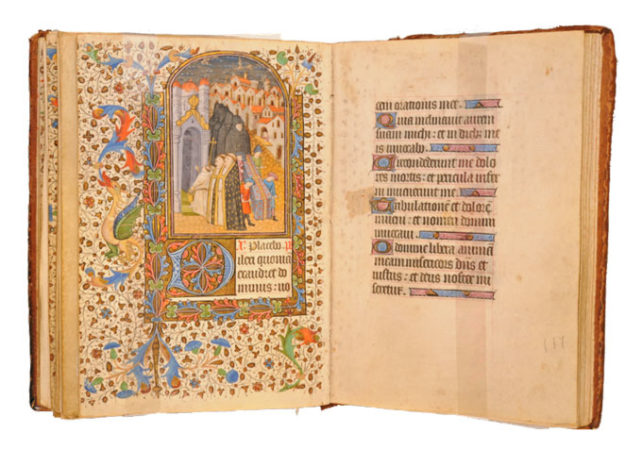

Called folium, this watercolor had been used to paint images on the pages of medieval manuscripts. But long ago, it fell out of use. Now scientists have tracked down folium’s source to a plant. They’ve also mapped out the molecule that produces its blue hue.

Such chemical information can be key to conserving art. “We want to mimic these ancient colors to know how to … preserve them,” explains Maria Melo. She works at Universidade Nova de Lisboa in Caparica, Portugal. There she studies ancient art and how to preserve or restore it. To unmask folium’s identity, her team had to first find out where it came from.

The pigment hadn’t been used for centuries. Everyone who knew how to prepare it had died long ago. So the researchers turned to books from the 1400’s and found one that described the plant that was its source. That led them on a scavenger hunt to find living specimens of this plant.

They enlisted the help of a botanist, a scientist who studies plants. The team landed on Chrozophora tinctoria (Croh-ZOFF-or-uh Tink-TOR-ee-uh). They found this tiny herb with silvery-green leaves in a village in south Portugal. It was growing along roadsides and in fields after harvest. The team gathered its pebble-sized fruit with care.

Back in the lab, the scientists extracted the pigment with the help of a medieval text on colors. “It’s very specific,” notes Paula Nabais. She’s a conservation scientist who was part of the research team. “So we were able to use that recipe [and] reproduce it.” Nabais also works at Universidade Nova de Lisboa.

“That’s pretty cool to have done that work of looking in the historical recipes and traveling back in time,” says Francesca Casadio. She’s a chemist and museum scientist at the Art Institute of Chicago in Illinois. Casadio, who was not part of this study, says the new work is a good example of what’s called experimental archaeology. It recreates an ancient process. By making the dye, the scientists could study its chemistry without experimenting on priceless works of art, she points out.

‘New science from old books’

The researchers used many techniques to analyze the dye and identify its chemical structure. They reported how they did it April 17 in Science Advances. They also simulated how light interacts with the candidate molecule. That helped the scientists check whether the structure would give them the blue they desired.

Knowing a paint’s chemistry helps conservation scientists know how to preserve art that used it. For instance, these data might be used to slow a paint’s degradation. Or if the piece needs to be restored, museum scientists can find compatible pigments. “This is absolutely vital to conservation,” says Mark Clarke. He’s a conservation scientist at Universidade Nova de Lisboa. He was not part of this team but has studied folium before.

Folium had presented scientists with a difficult chemistry puzzle. “People have been tinkering with [this dye] since the ‘30s and they’ve finally cracked it,” he says.

This team succeeded because it brought together experts from fields as diverse as chemistry, botany and medieval literature. In the end, Clarke says, you’ve got “new science from old books.” And, he adds, these very modern things are being used to answer “very old problems.”