New COVID-19 vaccines show promise in people

Treated volunteers made antibodies and immune cells against the new coronavirus

A volunteer gets vaccinated in the United Kingdom. She doesn’t know if what she received is directed against the new coronavirus or a meningitis-causing bacterium. Oxford researchers conducted this trial as a test of the safety of their new COVID-19 vaccine.

University of Oxford

As the coronavirus began to spread in China late last year, science teams around the world lined up along a starting line. They were waiting for a signal to start the race to make a COVID-19 vaccine. That signal came on January 10. That’s when scientists in China shared the complete genetic makeup of the new coronavirus.

With that information in hand, many researchers began sprinting toward a new vaccine. The race remains neck-and-neck even as it gets much closer to the finish line. In May, data from one trial in people showed promise. This week, scientists shared initial details from tests of several more candidates.

The immune responses they produced in the treated volunteers suggest a vaccine to protect people against the killer virus might be close.

Of nearly 200 vaccines now underway, more than 20 already are being tested in people. Some experts predict a vaccine could be ready for emergency use by the end of December.

So far, a number of these candidates can successfully train people’s immune systems to recognize the new virus. Not the whole virus. Just a part of it known as the “spike protein.” Like the name suggests, this protein looks like a spike on the outer shell of the new coronavirus.

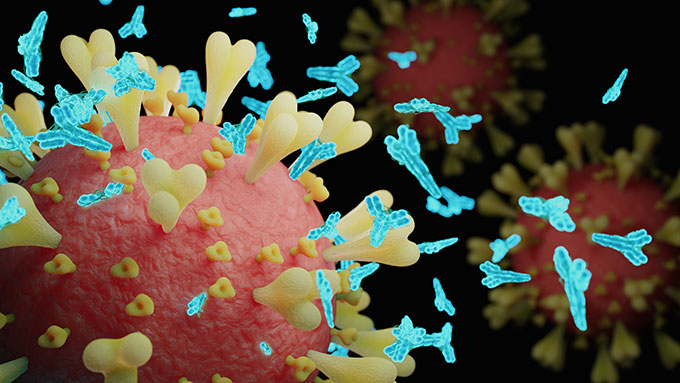

The immune system recognizes this is not a human protein. That quickly kicks the immune system into action. It starts making antibodies that attack the spike protein. It also trains a type of white blood cells — called T cells — to hunt down anything with that protein. That will include the coronavirus, if it shows up.

Training to fight the ‘spike’

The first coronavirus vaccine to be tested in people was developed by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, in Bethesda, Md., and a biotechnology company. That company, Moderna, is based in Cambridge, Mass.

People in this study were given different doses of the vaccine to see if it was safe. On May 18, Moderna issued a press release. Those who got the vaccine produced antibodies, the release said. Lots of them. They made as many or more antibodies against the coronavirus as do people who had recently gotten over COVID-19. Moderna and NIAID published more detailed results of this study July 14 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The new vaccine uses what’s known as messenger RNA (mRNA). This RNA carries genetic instructions for building a cell’s proteins. In this case, it delivered ones telling human cells how to make the spike protein. When the cells did, the immune system attacked that protein.

Another new vaccine just passed its first safety test, too. It was developed in England at the University of Oxford. This vaccine also prompts human cells to make the spike protein. It uses a different delivery van to drop off instructions for making the spike protein. The virus this vaccine uses is one that normally infects chimpanzees. Human cells read the instructions this virus brings to make the coronavirus protein. Then the immune system does its work.

More than 1,000 healthy adults between the ages of 18 to 55 volunteered to take part in the Oxford trial. Each got either the new coronavirus vaccine or a vaccine against bacteria that can cause meningitis. That second vaccine was used as a comparison group. The volunteers who got it developed sore arms and other side effects that wouldn’t give away that they had not received the coronavirus vaccine.

All who got the coronavirus vaccine made antibodies against the spike protein. They also made those T cells that are so important for long-lived immunity. The Oxford group is working with the big drug company AstraZeneca. Their team shared its new findings July 20 in a British medical journal, The Lancet.

Antibodies can block the ability of a virus to enter cells. Levels of them in people who got the Oxford vaccine were as high as what’s seen in people who have recovered from COVID-19. There were some side effects, such as fever and arm pain. Acetaminophen (Ah-SEE-tuh-MIN-oh-fen), better known as Tylenol, helped people deal with these.

Work on other viruses suggest that antibodies and T cells should guard against infection or serious illness, notes Mark Poznansky. He was not involved in the study. But he knows plenty about such treatments. He directs the Vaccine & Immunotherapy Center. It’s at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. (His group is devising its own COVID-19 vaccine.) For the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine, he says, “The results so far are encouraging.”

After one dose, 32 of 35 participants for whom data are available had neutralizing antibodies against the spike protein. After two doses, all 35 had the antibodies.

The researchers plan to give two, high-dose injections in further trials, they said at a July 20 news conference.

However, one basic question remains: How big an immune response will be needed to guard against COVID-19? It also is too early to know how long antibody levels remain high. Indeed, Poznansky says, it won’t be clear whether this vaccine truly is safe and effective until many more people get it.

If the vaccine does prove successful, AstraZeneca and Oxford have committed to providing 2 billion doses of it. More advanced clinical trials to test the vaccine’s efficacy are now underway. In the United Kingdom, almost 10,000 volunteers have gotten the vaccine. A trial in Brazil will give it to 5,000 more. And in a week or so, a U.S. trial of the vaccine will begin treating another 30,000 people.

More human trials also show similar promise

CanSino Biologics is a company based in China. This week, the company reported data from a safety trial that included more than 500 volunteers. Some got a high dose. Others got a low one. Both doses produced antibodies and T cells against the virus, according to a July 20 report in The Lancet. (The Chinese government has already approved temporary use of this vaccine by its military.)

This vaccine was made by altering a common cold virus. It’s called adenovirus 5. The researchers tweaked it to make the coronavirus spike protein. Many people in the study already had antibodies against adenovirus 5. That makes some experts worry that this vaccine might not be very effective.

Pfizer is a big, global drug company. It has been working with the German biotech company BioNTech on yet another COVID-19 vaccine. Like the Moderna candidate, it too uses mRNA. Early tests of it in 60 volunteers were published July 20 at medRxiv.org. They show that two doses appear safe and stimulate the body to make antibodies. Their latest data show that the vaccine also produces T cells against the coronavirus spike protein.

How long before we know which really works?

Antibodies can sometimes help viruses get into cells instead of stopping them. So scientists will be looking for signs that any of the new vaccines make COVID-19 worse. More importantly, they’ll need to test whether the vaccines actually prevent disease. To test that, treated people must later become exposed to the novel coronavirus.

Observes Poznansky, “It’s the irony of ironies that where the virus spread is out of control may be the optimal place to test the vaccine.” That might well describe the United States today. Researchers need a high rate of community spread. If not, they won’t be sure that differences between treated and untreated groups are due to protection from the vaccine (and not just that vaccinated volunteers never came into contact with someone who was infected).

President Donald Trump mentioned the new vaccines on July 21. It was his first coronavirus press conference in months. “Ultimately, our goal is not merely to manage the pandemic but to end it,” he said. “That is why getting a vaccine remains a top priority.” Trump added that “we’re mass producing all of the top candidates so that the first approved [COVID-19] vaccine will be available [as soon as its ready].” Indeed, news reports this week noted the United States has already spent $1.95 billion to buy 100 million doses of the Pfizer/ BioNTech vaccine.