Viral scents? Dogs sniff out coronavirus in human sweat

Some trained trackers are super-sniffers, accurately identifying infected people in dozens of tests

Phoenix is a search and rescue dog with a fire department in France. Here she is being tested to see if she can correctly identify the smell of someone infected with the virus that causes COVID-19. Each box contains sweat samples from either an infected or uninfected person.

Nosaïs

Sweat from people infected with the virus that causes COVID-19 has a distinct smell. We can’t detect it. Dogs, it now turns out, can.

Over the past few months, research teams around the world have been training dogs to sniff out this coronavirus. Some dogs are so good they can find it 100 percent of the time over the course of dozens of tests.

“Just like humans, some dogs are more clever than others,” observes Dominique Grandjean. He’s a researcher at France’s National Veterinary School in Maisons-Alfort. He also oversees the training of French search and rescue dogs that work with Paris firefighters and emergency responders.

Grandjean’s team was among the first to show that dogs could be trained to detect the coronavirus in infected people. Starting in March, these researchers collected sweat samples from the armpits of volunteers. Some were infected, others weren’t.

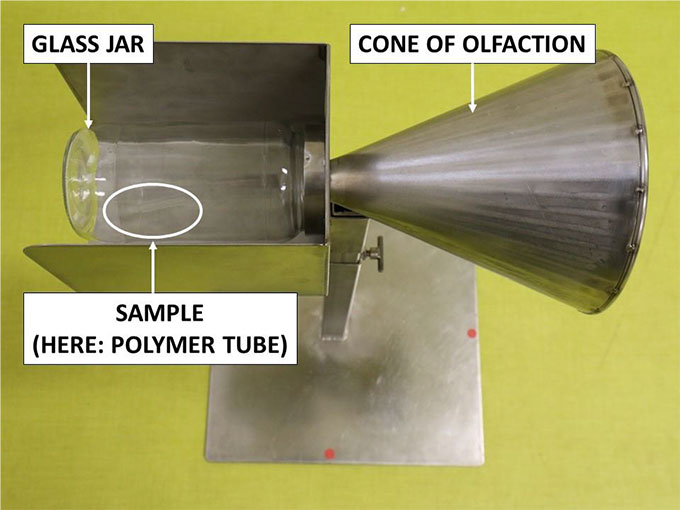

The team swabbed a roll of clean cotton under each volunteer’s arm for one minute. Then the researchers dropped the cotton into glass jars. Each jar was topped with a steel cone into which dogs could put their muzzles. This allowed the canines to sniff a sample without touching it.

The researchers did this to keep the dogs safe. No studies have yet turned up the virus in human sweat. But the researchers were being careful. A few dogs around the world have become infected with the virus. None, however, is yet known to have been sickened by it.

The new study used samples from people who tested positive for the virus and had symptoms. This is important. Some people can be infected but show no symptoms. This allows them to unknowingly spread it to others.

Grandjean’s group has now begun testing dogs with the sweat of infected people who do not show symptoms. Early results suggest the dogs can identify these people, too.

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

How the dogs were tested

Eight Belgian Malinois (BEL-juhn MAL-uhn-wah) shepherds were used in the first tests, those on samples from people with symptoms. The dogs had been specially trained. Most of the dogs had been working with firefighters and emergency responders. Some had been trained to sniff out people buried under rubble after an explosion. A few others had been trained to help doctors diagnose disease. They did this by identifying a telltale gas emitted out the rectums of people with colon cancer.

All of these dogs then learned to identify COVID-19. They trained by sniffing inside the steel cones attached to five lined-up sample jars. When a dog sat down in front of a cone containing a virus-positive sample, its trainer rewarded it with a favorite toy. Every dog has one — a tennis ball or a braided rope, for example. “My dog likes a small pink plastic hippo,” says Grandjean.

Once the dogs understood what their trainers wanted them to look for, the researchers started making the tests harder. They moved the position of the virus-positive sample in the line. They added more positive samples. Then they replaced them with samples from healthy people.

Over dozens of such trials, four of the eight dogs had perfect scores. The worst-performing animal still judged at least eight in every 10 samples correctly.

The results were uploaded in early June to bioRxiv, a science website. They have not yet been peer reviewed. That means other scientists in this field have not reviewed the test methods and outcomes. (Those steps are usually essential before a study gets accepted for publication in a research journal.)

Still, the findings already have gotten notice. And other researchers — including ones in Australia, Lebanon, Argentina and Brazil — have begun reporting similar results.

Meanwhile, researchers in Germany are taking a slightly different path to canine detection of COVID-19. Their dogs are sniffing saliva samples. Just as in the study by Grandjean’s team, the dogs don’t touch the samples. They again sniff samples through a steel cone.

To sniff or not to sniff

Exposing dogs to saliva samples worries Colin Furness. He’s an epidemiologist, or disease detective, in Canada at the University of Toronto. The virus that causes COVID-19 can be transmitted in droplets from infected people’s mouths when they speak, cough or sneeze, he notes. “Using sweat sounds a lot safer to me,” says Furness, who did not take part in either study.

Furness was not surprised to learn dogs can sniff out COVID-infected people. After all, they have a much better sense of smell than do people. They’ve already been used to detect diseases such as cancer and Alzheimer’s disease, he notes.

“I think COVID-sniffing dogs could be really useful in schools,” says Furness. “Let the dogs give the kids a sniff.”

Grandjean says that certainly should be possible. But some people fear dogs. That’s why getting them to sniff sweat from cotton swabs is probably better, he says. In fact, sniffer dogs are already working to identify infected passengers at an airport in the United Arab Emirates by smelling swabs rubbed on the travelers’ armpits.

Grandjean would like to see more airports and border crossings use dogs to find infected people. Conventional laboratory tests for the virus take at least 24 hours to deliver results. “The dogs can give you a positive result immediately,” he says.