Dust can infect animals with flu, raising coronavirus concerns

Three of 12 guinea pigs that were immune to flu spread the virus through contaminated dust

Viruses like influenza — and potentially the new coronavirus — may spread via dust from virus-contaminated objects (like blankets or tissue paper), a new guinea-pig study finds.

DevMarya/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Spewing virus-laden droplets may not be the only way people and other animals send viruses into the air. Germs like the flu virus can also hitch a ride on dust and other airborne particles that we shed. That’s the finding of a new study in guinea pigs.

People can transmit respiratory viruses, such as those that cause influenza and COVID-19, just by talking, singing, coughing and sneezing. Virus-tainted surfaces are known as fomites. These, too, can also cause infections. People need only touch the surface and then bring their contaminated hands to their nose or mouth.

Now research suggests that dust particles can become fomites, too. And such aerosols (airborne particles) may spread infectious germs.

“Our work suggests that there is a mode of [virus] transmission that is underappreciated,” at least for flu, says William Ristenpart. He’s a chemical engineer at the University of California, Davis. These formite aerosols, he notes, definitely are “not on [scientists’] radar.”

His team’s study, published August 18 in Nature Communications, did not include the new coronavirus, known as SARS-CoV-2. Ristenpart notes, however, that his groups new finding could have implications for that virus too.

Studying viral dust-ups

For their new study, Ristenpart and his colleagues infected guinea pigs with a flu virus. Two days later, they found infectious virus in the cages as well as on the animals’ fur, ears and paws. Infected guinea pigs don’t cough or sneeze as people do. So the virus may have spread when the rodents groomed, rubbed their noses or moved around.

The researchers then used a brush and “painted” virus onto animals that had been infected and were now immune. Each virus-covered rodent was put in its own cage. They remained near to a cage with an uninfected companion. This ensured that the only way to spread the virus from one animal to another was through the air.

The flu-covered immune rodents were not exhaling virus into the air. Still, three of the 12 susceptible (not immune) guinea pigs got infected. These animals may have gotten the virus from the dust kicked up by the virus-painted animals.

“It’s not that all dust is infectious,” Ristenpart says. However, he suspects this could be true of “dust liberated from a virus-laden surface.”

In human settings, that dust might come from used tissues, sheets or blankets. Or perhaps from a doctor’s personal protective equipment or a cloth mask. In a preliminary study that has not yet been reviewed by other researchers, Ristenpart and his team found that homemade cotton masks can shed minuscule particles as people breathe. This might make them a potential source of fomites in air.

Airborne dust

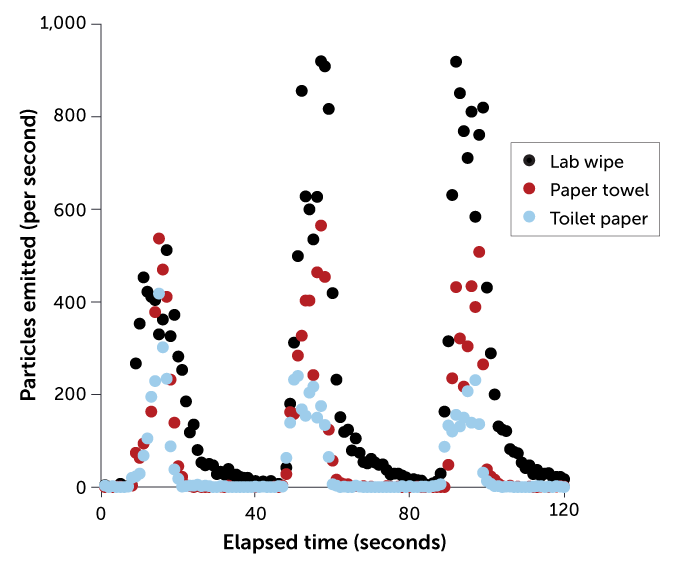

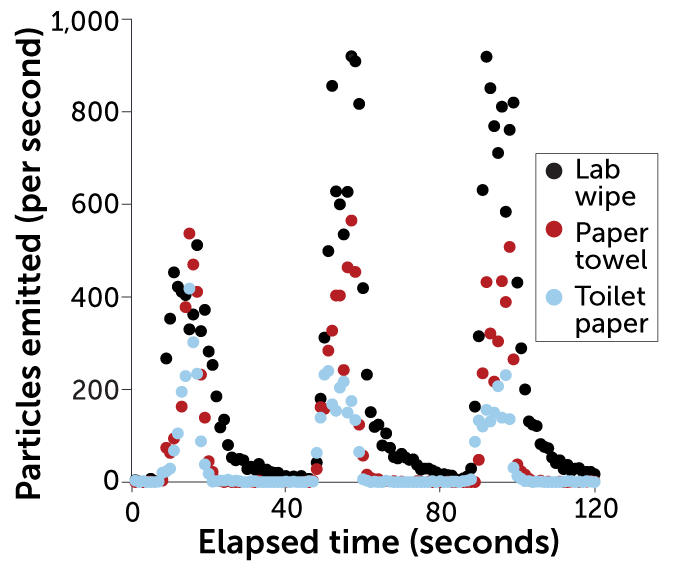

Some common items people use could be potential sources of virus spread via aerosolized fomites or dust kicked up from surfaces. The graph shows the number of particles emitted per second over time when rubbing together pieces of toilet paper (blue), paper towel (red) and lab wipes (black) to produce dust.

Dust particles emitted from household items over time

This is not the last word

It’s unclear what the results might mean for the spread of viruses between people. The data suggest flu fomites in the air might be capable of causing infections. First, people would have to breathe in the fomite aerosols, notes Julian Tang. He was not involved in the new study. But he understands the concept. He is virologist at the University of Leicester in England. Part of his work involves studying the motions of fluids (such as air).

Dust from guinea pig bedding may become airborne much more easily than from a mask, doctor’s protective gown or bed sheets. So, compared with exhaled flu virus — or SARS-CoV-2, Tang says, “I’m really not convinced that in humans, this aerosolized fomite route will play any [major] role.”

Researchers are still figuring out all the ways the new coronavirus spreads. The World Health Organization, part of the United Nations, is based in Geneva, Switzerland. For months, the WHO had downplayed how long tiny aerosols might remain in the air and infectious. Then, on July 6, more than 200 experts signed an open letter to the WHO. In it, they said it’s time the health community accepts that infectious coronavirus can remain airborne. Their letter appeared on July 6 in Clinical Infectious Diseases. It asked the WHO to point this out.

Fomite in air can transmit other viruses, too. Hantavirus causes another deadly respiratory disease. It can be transmitted through kicked-up dust that has been in contact with dried rodent droppings. Unlike flu and COVID-19, however, that infection does not spread between people.