Around the world, birds are in crisis

Climate change, habitat loss and other factors are leading to their decline

A western meadowlark sings on the prairie. This is one of many species that has been rapidly disappearing.

Matthew Pendleton/Macaulay Library at Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Scott Edwards paused his cross-country bike trip when he spotted a flash of black, white and red. It was a red-headed woodpecker. “I got my first good look today,” he said. He was phoning from his tent in Illinois later that night. He had seen their distinctive black and white wings while riding. “But I hadn’t seen the red head until today, so I was very excited.”

Edwards is an ornithologist — a bird researcher — at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass. Over this past summer, he rode across the United States. In part, he did it to see the country. But he also used the trip to do some serious bird-watching. That’s something he’s been doing for more than 40 years.

When he was growing up in the Riverdale neighborhood of the Bronx, in New York City, there were lots of trees, he recalls. When he was nine or 10, a neighbor took him bird-watching. Edwards has been doing it ever since. But finding https://www.birdlife.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/SOWB2018_en.pdfthose birds is getting more difficult. “It’s quieter,” he says of their songs and calls. “The numbers [of birds] are way down.”

And Edwards is hardly the only one to notice it. Scientists around the world have been finding the same thing.

A 2018 study by BirdLife International concluded that birds around the world are in trouble. There are about 11,000 species of birds. Four in every 10 species of them are decreasing in number, the study found. That’s true for all kinds of birds living in all types of habitats.

Some birds, such as the red-cockaded woodpecker and California condor, are critically endangered. Only a few members of these species remain in the wild. Others are frequently spotted at backyard feeders: sparrows, finches, warblers and more. But even common birds are less common than they were just 50 years ago. And that’s now true almost everywhere.

Billions of birds gone missing

In 1803, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark led an expedition into the wilds of western North America. When they started their trip up the Missouri River, they encountered millions of birds called passenger pigeons. Huge flocks blocked out the sun for hours on end. The entire passenger pigeon population at the time probably numbered in the billions. But just over 100 years later, the birds were no more. The last passenger pigeon, named Martha, died in the Cincinnati Zoo in Ohio. Her species had been wiped out by hunting and habitat loss.

The passenger pigeon was once the most abundant bird in North America — maybe even on the planet. Then it was extinct. People could now see that it was possible for incredibly common species to disappear forever.

Extinctions are pretty rare. But North America is losing lots of birds, says Kenneth Rosenberg. He is an ornithologist at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. That’s at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. He was just one biologist who noticed changing bird populations in the mid-2000s. “We knew many bird species were declining,” he says. But “some, like ducks, had been increasing.” What the researchers didn’t know was whether the increasing species made up for the losses. Were bird numbers, as a whole, staying steady?

In 2017, Rosenberg teamed up with scientists from across the United States and Canada to find out. The group turned to long-term bird surveys for their study. These surveys go back to 1970. Created by scientists and government agencies, they help researchers understand bird numbers, migration patterns and more. Researchers use them to create bird-identification guides and conservation plans. These surveys estimated population sizes for 529 bird species across North America.

The team found that species living in wetlands are doing well. Ducks and geese have increased in number over the past 50 years. “Waterfowl hunting contributes millions of dollars for wetland protection and management in order to have healthy populations for hunting,” Rosenberg says. Those efforts are helping waterfowl populations overall.

But birds in other habitats are struggling. From coasts and forests to tundra, populations of birds have been declining, the analysis found. The biggest changes are in grassland species, especially sparrows, blackbirds and larks. That’s because 90 percent of their habitat has been converted to agriculture, Rosenberg says. Their populations are less than half what they had been in 1970.

Species that live in other habitats are suffering, too: warblers, finches, flycatchers, swallows, sandpipers and more. Overall, North America has lost three billion birds, Rosenberg’s team estimated in an October 2019 Science study.

Birds can be divided into two groups: those that live in one place all their lives, and others that migrate from one home to another. As part of the same study, Rosenberg’s team found evidence that migrators may face the greatest risk.

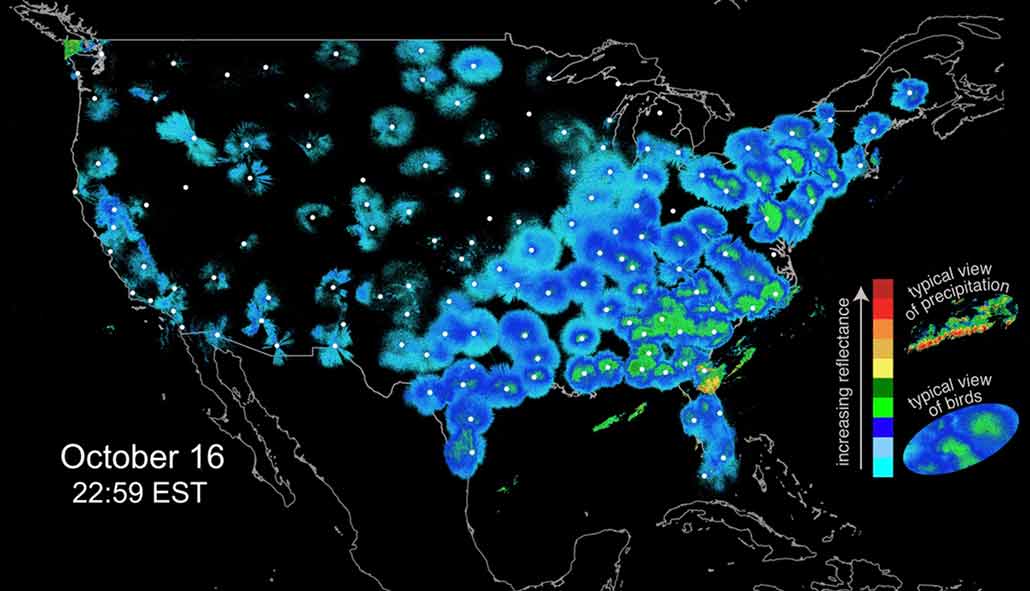

NEXRAD weather-radar systems are designed to track storms. But they also track large masses of any type of moving object. That includes flocks of birds. Many migrating birds travel at night. It’s cooler and less windy, and smaller birds will be safer from predators. Although it’s possible to hear them go by, it’s a challenge to know how many individuals are flying overhead. “NEXRAD makes it possible to see the migrating birds,” Rosenberg explains.

His team analyzed weather radar data recorded during spring migrations from 2007 to 2017. This showed where birds traveled. The researchers estimated population size based on how large the mass was on the radar. Numbers of migrating birds dropped over the 10 years his team tracked them with radar. This finding matched what long-term surveys showed. Migratory species have dropped by about 2.5 billion individuals since 1970, those surveys had shown. But numbers of bird from species that stayed in the same area all year remained fairly stable, Rosenberg says. That includes birds like the American robin, blue jay and chickadee.

The trouble with migration

Such trends aren’t limited to North America. Birds are declining in Europe, too, notes Franz Bairlein. He is an ornithologist at the Institute of Avian Research in Welhelmshaven, Germany. Migratory birds are in the most trouble there, also. Long-distance migrants travel from their breeding grounds in Europe. They end up in Africa, where they overwinter. Bairlein’s research has found three main reasons for the decline in these birds.

Tens of millions of birds are killed illegally when they stop to refuel at spots along their journey. This hunting of the birds could be for food, trade, tradition or just for sport, Bairlein says. It doesn’t take long for those losses to affect a population. But illegal killing isn’t the major problem facing these species, he says.

A much more widespread concern is the severe destruction and loss of their habitat, he says. That’s true, he adds, “almost everywhere: at breeding grounds, stopover locations and winter locations.” All along the migration routes, people are changing the landscape in ways that imperil birds. In some areas, natural landscapes have become farm fields that no longer provide the food or shelter that birds need. In other areas, buildings and roads have been replacing these landscapes.

Lastly, there’s climate change. The spring thaw now arrives earlier and earlier. When temperatures get warm enough, caterpillars and other insects emerge from their winter hideaways. Many birds, such as the pied flycatcher, rely on fat insect larvae to feed their young. But in many years now, the migrating birds arrive too late to catch the caterpillars. When this happens, the birds’ young go hungry and may die. This, too, can affect a population’s size, Bairlein says.

Climate change also will lead to longer migrations. That’s the finding of a 2018 study in Proceedings of the Royal Society B. Its authors, Christine Howard and Stephen Willis, are conservation ecologists at Durham University in England. The pair looked at 77 bird species that breed in Europe. They estimated the distances each species currently migrates. Then they used a computer model to see how changes in climate might alter these distances over the next 50 years.

Climate isn’t changing at the same pace and in the same way everywhere. Some regions are getting hotter faster than others. Some are becoming drier. Or wetter.

The researchers found that summer breeding grounds will shift by about 415 kilometers (258 miles) by 2070. Many of those shifts will be to the north. “We expect that as temperatures increase, many species will have to travel towards the poles to find areas of suitable climate,” Howard says. The birds’ migrations will take several days longer than they do now. And that means birds will need extra stopovers to refuel along the way.

“Migration is a period of high mortality,” Howard says. Birds use lots of energy on the long flights. So starvation is a risk, she says. Stopovers are critical if birds are to safely reach their destination. They let birds refresh and refuel along the way. But these rest stops require suitable habitat — areas that provide good shelter and the right types of food.

“Any increase in reliance on stopovers might render birds more vulnerable to habitat changes in these locations,” Howard says. In some cases, there may “not be suitable habitats” when the migrants need them.

Bird populations aren’t as well studied in China and Russia. But even the limited data from those countries reveal a similarly dire situation. One study of yellow-breasted buntings in China found that this once-abundant species is rapidly disappearing. These birds are a traditional food in China. As the bunting populations began to drop, the government outlawed hunting them. But the new law didn’t stop people from continuing to capture and eat the birds. In just 33 years, the numbers of yellow-breasted buntings dropped by 84 percent. Another study by Chinese researchers found almost all songbirds that fly through eastern China to breed in Russia are declining in number.

Getting to the root of the problem

Knowing why birds are declining is necessary if scientists are to help bird numbers rebound. As studies have shown, climate change and habitat loss are two major problems. They’re also connected. Changes in climate can lead to dying vegetation, erosion of important habitats or changes in food supplies. These issues span countries and continents, making them tough to tackle.

Around the world, scientists are working to protect important habitats. But “we still don’t understand fully the stopover locations that individual species are using,” Howard says. And that makes it tricky to know which areas are essential for migration. A changing climate makes identifying those areas even harder.

Which areas should you protect? Howard asks. “Areas that are important now [or] areas that are important in the future?” Or perhaps, she says, some mix of both.

“Extreme climate will have a major impact on birds,” says David Lindenmayer. He is a landscape ecologist at Australian National University in Canberra. “It’s already changing bird body size,” he notes. Birds are getting smaller as temperatures climb. That can make it harder for them to store enough energy for long migrations.

Extreme weather events such as drought and flooding also destroy important habitat. Fires that ravaged Australia in late 2019 and early 2020 were so intense that they ravaged habitats that don’t typically burn. “Birds will be heavily impacted by [the] fires,” Lindenmayer says. “Many species were declining well before the fires, so this adds an extra challenge for them to deal with,” he notes. “It will be a long time before many species are able to return to pre-fire levels.” Some species may go extinct, he says. But others will persist or colonize burned areas.

Climate, weather and habitat loss aren’t the only problems that birds face. Scott Loss has examined more direct causes of bird deaths in North America. Loss is a conservation biologist at Oklahoma State University in Stillwater. He teamed up with ornithologists Tom Will and Peter Marra. Will works for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Bloomington, Minn. Marra is at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. The trio examined bird deaths in North America to figure out the major causes. And they turned up a wide range of problems.

By far the biggest: free-ranging cats. This includes feral, or wild-living, cats. It also includes pets that are allowed to roam free. Skilled hunters, cats kill an estimated 2.4 billion birds in the United States and Canada each year.

Collisions also kill millions of birds each year. Birds fly into windows, communication towers, wind turbines, cars, trucks and power lines. Tall structures pose a particularly big problem for migrating birds. Many-story buildings, towers and wind-turbine blades can reach well into the path of some migrating birds. Towers that require guy wires to hold them up are more dangerous still. Their support cables are invisible to night-flying species.

Lights can also pose problems. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) requires tall structures to have lights at night. These show pilots where the structures are located, so they won’t fly into them. But night-flying birds are attracted to steady-burning lights. Unlike the pilots, these birds don’t realize something is blocking their path. Many will fly right into it — or circle around it, burning up essential fuel in the process.

Long-distance migrants “use cues like stars and magnetic fields to orient,” Loss explains. Bright light disrupts those cues, causing birds to become confused, he says. The good news: Flashing lights don’t have this harmful effect. In fact, the FAA now recommends that towers use non-white, flashing lights to protect migrating birds.

And then there are pesticides, which are widely used both on crops and in urban areas. Birds can die from consuming pesticide if it’s on seeds or insects, Loss says. In fact, pesticides are one of the main reasons why grassland birds are declining so fast. Birds also can die by eating prey that have been poisoned, Loss notes. Raptors, such as eagles, hawks or owls, are at risk of eating contaminated prey if people put out poison for rats or other pests.

All is not lost

“Birds are telling us what’s going on in the larger environment,” Rosenberg says. “And that story is not good.” But we can make changes to help birds. Some are easy. Turning off lights in buildings at night, for instance, will keep those lights from attracting birds. Putting surfaces that reflect ultraviolet light on glass can help daytime fliers spot windows before they fly into them. So can objects or patterns placed on or in front of windows.

Changes are already coming to communication towers. Their steady-burning lights are being replaced with flashing ones. And keeping cats and dogs indoors helps birds, small mammals, reptiles and more. It protects the pets, too — from other dogs or cats, predators, and cars that could injure or even kill them.

Closer to home, teens can help birds, as well. “Make your parents sensitive to the causes of bird declines,” Bairlein says. Talk to them about making your backyard bird-friendly by planting shrubs that provide both food and shelter. Ask local decision-makers “to make public parks bird-friendly.” Even reach out to farmers and foresters, he suggests. Ask them “to protect habitats and increase habitat structures.” This might include planting hedgerows or bushes to create more varied landscapes. Need more ideas? Check out Rosenberg’s 3billionbirds.org for more ways you can help.

Lastly, do your part to fight climate change. Think about how you can personally reduce your impact. And “write your concerns to politicians,” says Lindenmayer. Tell them you want them to take steps to slow climate change.

“Bird populations can be very resilient, once we remove the threats,” Rosenberg says. So get involved. Become a citizen scientist and collect data on birds. Be a voice for change. After all, a healthy planet isn’t just for the birds.

Correction: Kenneth Rosenberg at Cornell teamed up with scientists from across the United States and Canada in 2017, not 2007 as previously stated.