What the mummy’s curse reveals about your brain

Here’s why it’s easy to confuse random coincidence with meaningful patterns

Would you fear entering a mummy’s tomb? The myth of a mummy’s curse grew in part because of a coincidence. A British lord died soon after opening up a long-lost tomb. Despite the fact that there was never any scientific evidence to link his death to the mummy, the story of that curse lives on.

Fergregory/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Two men peered through a small hole in the wall of a tomb. It was the final resting place of an ancient Egyptian king. “Can you see anything?” asked one. “Yes, wonderful things,” answered the other. Statues and golden treasure glinted in the dim light.

The two men were Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon. For six years, Carter had been searching for a lost tomb. Carnarvon paid for the expeditions. Finally, in November 1922, the men and their workers had found what they sought. The treasure-filled room was one of four associated with the tomb of Tutankhamen. This pharaoh, or king of ancient Egypt, had died in the 1320s BC. He was just 18 or 19 years old.

The discovery captivated the world. But Lord Carnarvon did not get to enjoy it for long. He died unexpectedly the next April at the age of 56. This was six weeks after opening and entering the actual burial chamber of the tomb.

Doctors said an infected mosquito bite killed him. But was it just coincidence that this came so soon after going into an ancient tomb? Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (creator of the famous detective Sherlock Holmes) didn’t think so. He wondered if an evil spirit might have caused the death. Was Tutankhamen so unhappy about the disturbance of his tomb that he somehow took revenge from beyond the grave?

The short answer: No.

Science has never found any evidence of spirits lasting beyond death, nor of any way that a spirit (if it existed) could influence the living world.

Egyptologists working in tombs today don’t fear for their lives — at least not from vengeful spirits. “I look at mummies and study mummies,” says Salima Ikram. And, she points out, “I’m still alive.” Ikram is an Egyptologist at American University in Cairo, Egypt. If she worries about anything during her work, she says, it’s snakes or collapsing debris.

To some people, however, the fact that a person entered a tomb and then died soon after seemed too strange to be a coincidence. So the claim of a curse became legend.

Much more mundane coincidences regularly pop up. Perhaps you’ve picked up your phone to text a friend, only to find that a text just arrived from that same friend. Or maybe you had a dream about getting a pet cat the night before a stray showed up on your doorstep. These types of experiences may seem so meaningful — and unlikely — that they must be connected. Yet events that seem linked often aren’t.

So why do people see connections that aren’t really there? And how can we decide whether a connection truly exists? Scientists who study coincidences are helping to find the answers.

The lion in the grass

Over time, others who entered Tutankhamen’s tomb also died. With each death, the idea of a mummy’s curse became more convincing. Some scientifically minded people questioned whether toxic mold or bacteria in the tomb might have led to the deaths. But all these people missed a very important point. In science, before you look for a cause, you must rule out what’s known as the null hypothesis.

It proposes that nothing special is going on. No connection exists.

To test for the absence of a link, you need to know how likely it is for the events to happen at random. And to do that, you need to look at the big picture.

In 2002, a researcher did just that for Tutankhamen’s curse. Mark Nelson works at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. He identified 44 people from Europe who were in Cairo when the tomb was opened. Twenty-five had entered the tomb or worked with the mummy. The rest had done nothing that might expose them to a curse (if one existed). Both groups had average life expectancies.

Those data made it clear: People who encountered the mummy had no greater chance of meeting an untimely demise. In fact, Howard Carter lived another 16 years, dying of cancer in his mid-60s. If there really was a curse, he should have been one of its first victims.

So why did so many people believe in the curse? “It’s interesting and unusual,” says Ikram. “It’s kind of boring to think of the ancient Egyptians as being just like us,” she adds. “You want them to have special powers.”

A longing for excitement and mystery is one reason people might believe in a curse. But there’s also something deeper going on. “Our brains are wired up to find meaningful patterns,” says Michael Shermer. He’s the author of The Believing Brain. He’s also a famous skeptic, someone who questions or doubts information.

Connecting cause and effect is how all animals — including people — learn about their world. Most of the time, we learn real, meaningful connections. For example, if a mosquito bites you, you get an itchy red welt. If you see lightning, you soon hear thunder.

When we see only an effect, we tend to guess at its cause. A rustling sound in the grass makes most people feel a jolt of fear or surprise. Most likely the sound is just the wind. But it could also mean a lion or other large animal is nearby. The human brain evolved to assume the worst, explains Shermer. And here’s why: If it’s just the wind and you run, no harm done. But if the sound is a lion and you do nothing, he notes, “you’re lunch.” So it’s safest to assume something big and dangerous is hunting you.

This tendency to see connections between unrelated events or to believe in error that something or someone caused another thing to happen has a fancy name: apophenia (Ap-uh-FEE-nee-uh). Here’s another example. You’re a little kid in a dark bedroom and something goes “clunk.” The first thing you might imagine is not a book falling off a shelf but a monster under the bed. This is your brain trying to protect you. (Thanks, brain!)

You’re invited to a coincidence party

Coincidences are a perfect opportunity for imagining unlikely causes. If your favorite soccer team scores a goal while you’re barefoot, you may take off your shoes and socks for future games — just in case. If a song comes on the radio one minute after you start humming it, you may think you somehow made it start playing. If you run into a next-door neighbor in a distant city, you might suspect that fate or luck brought you together.

Most people realize there’s no real connection between these types of events. They’re weird and fun. And they happen to all of us now and then. So how can we tell when a connection is real (like lightning and thunder) or imagined (like your bare feet and a soccer goal)? Use statistics. This is the science of collecting data and using math to understand its meaning. Essentially, statistics help you translate data into information.

Statistics can also determine how likely something is to happen, or whether two events are likely to be linked. Nelson used statistics to debunk Tutankhamen’s curse.

David Spiegelhalter studies statistics at the University of Cambridge in England. He also happens to be a knight. (“It was quite fun. You have to kneel down, and they put a sword on both shoulders.”) For almost a decade, he has been asking people to post their coincidences on a website. He’s even thrown coincidence parties. People who come hang signs around their necks listing their birthday, pet’s name, favorite movie and more. It’s thrilling and delightful when party goers find connections — but not unexpected. If you get a group of 50 people together, he notes, “it’s almost certain [at least] two will have the same birthday.”

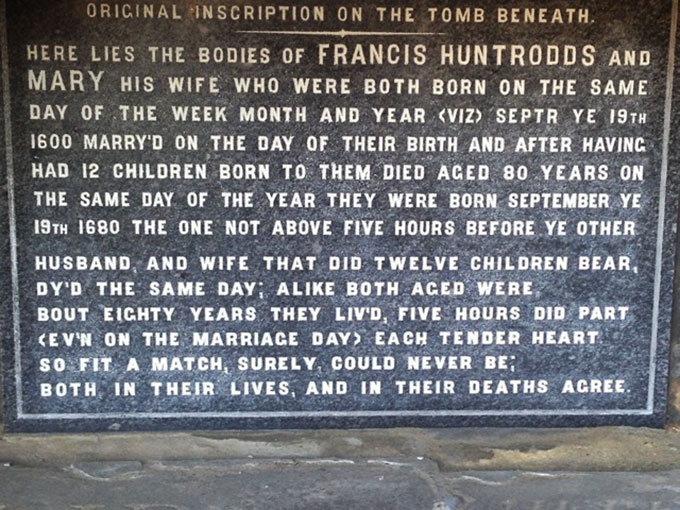

He holds these parties on September 19. Known as Huntrodds Day, the celebration honors Francis and Mary Huntrodds. They were both born on September 19, 1600, married on September 19, 1620, and died within hours of each other on September 19, 1680. Their story is much more unlikely than simply two people sharing the same birthday. But Spiegelhalter doesn’t think you need to turn to fate or luck to explain it. “There are so many opportunities for bizarre things to happen,” he says. If you wait and watch long enough, “really implausibly unlikely things will occur.”

For example, in July 2014, three major plane crashes happened over eight days. This series of tragedies seems very unlikely to happen randomly. But before you go looking for connections among the crashes (perhaps vengeful sky spirits?), remember the null hypothesis.

You need to ask how often similar events happen over a long period of time, explains Spiegelhalter. He looked at data on airplane disasters from 2004 to 2013. During that time, an air disaster happened about once every 40 days. The chance of three disasters in any stretch of eight days was very low. Still, probability showed a nearly six in 10 chance — better than 50:50 — of this happening at some point over a 10-year period. So that weekend in 2014 fit expectations. There was no reason, then, to suspect those crashes were more than a tragic coincidence.

In many scientific studies, researchers say their results have statistical significance. This means they have used math to show that the result they found was unlikely to have happened randomly. It suggests that they may have found a true causal connection, not some coincidence or random correlation.

That’s so random!

Randomness isn’t easy to recognize. Here’s a quick quiz: If you throw a die five times, which sequence is more likely, 3-1-5-3-2 or 1-1-1-1-1?

It was a trick question. Both are equally likely. But you’d find the second sequence much more surprising. Most people expect alternating, evenly spaced random numbers. They don’t expect repetitions and patterns, like three plane crashes in eight days or five 1s in succession.

But “random events don’t necessarily look random,” says Paul Rogers. He’s an independent researcher in Portsmouth, England, who studies psychology. People who don’t know this fact about randomness might assume that a sequence (like 5-4-3-2-1) or pattern (3-3-3-3-3) can’t be random. If there’s a pattern, some event or conditions must have created it. So they’ll look for a cause. And they may end up believing in an association that isn’t true. Such as a mummy’s curse.

Curses, vengeful spirits, an ability to predict the future and other such phenomena are called paranormal. The prefix means these things are “beyond” normal. Many people believe in the paranormal even though there is no scientific evidence supporting such beliefs.

Why do they believe? Trouble understanding randomness and probability may play a role. Psychologists have found that people who believe in the paranormal are more likely to see meaningful patterns in randomness.

Rogers has found that they’re also more likely to make another kind of mistake, called a conjunction error. It comes from thinking two events or conditions are more likely to occur together than happen alone.

Here’s one example. Imagine a young girl who just learned to ride a bike and is about to head down a steep hill. Which of these statements is most likely to be true? 1) She is worried about the ride. 2) She falls on the way downhill. 3) She’s worried about the ride AND falls on the way downhill. Picking choice 3 would be a conjunction error. Why? It’s always more likely for a single event to occur than for two events to happen at once.

Rogers gave volunteers 16 scenarios similar to this one. He also gave them a questionnaire about their belief in different types of paranormal events. People with more paranormal beliefs were more likely than non-believers to make conjunction errors. What mixes people up is that the third scenario above includes a cause and effect that seem connected. Worrying could lead to a mistake that makes the girl fall. But in fact, that connection doesn’t make the third scenario any likelier.

Someone who misunderstands randomness or probability may feel events must be connected. And they may be more likely to accept paranormal explanations. And vice versa: If someone believes in the paranormal, then they may see more connections among random events.

Random chance explains many coincidences. In other cases, a person simply may not accurately recall what happened. Remember the example of someone who dreamed of a pet cat and then found a stray the next day? This seems remarkable. But can this person trust her memory of the dream?

“We’ve all got imperfect memories,” says Rogers. Often, when a person remembers something, new details get mixed into the original memory. The person may have actually dreamed about a dog or a tiger. Or the dream may have contained a cat, but it occurred months before the real cat came — or even a day later. In real life, people often misremember which event came first.

Christian Rominger is a neuroscientist at the University of Graz in Austria. He wondered whether memory errors might help explain some experiences that seem more than mere coincidences.

In 2011, and again in 2019, he did experiments looking at whether people who experience meaningful coincidences also make more memory mistakes. Rominger gave participants a survey. It asked about their experiences of coincidences and their belief about what those coincidences mean. He also tested their memories while measuring their brain activity.

People who experience more meaningful coincidences made more memory mistakes, Rominger found. They also “had to make more effort to hold information in mind,” he says. They were working harder to remember things. This difficulty with memory might help explain why they find more meaning in what others see as coincidence. They may have been remembering events as more coincidental than they truly were.

The importance of imagination

Good scientists are skeptics. When faced with events that seem connected, they first assume that the null hypothesis — no connection — is true. Then they perform experiments and use statistics to test for any evidence of causality.

While it’s wrong to assume that a mysterious force caused some particular event, it’s also wrong to immediately dismiss all coincidences and patterns as being due to random chance. Good scientists are always thinking about possible connections and possible causes. “If you aren’t noticing patterns, you don’t make a new scientific discovery,” says Magda Osman. She’s a psychologist at the University of London’s Queen Mary College, in England. If a pattern of events seems too strange to be a coincidence, then challenge yourself: Ask questions and investigate to find some normal explanation — not a paranormal one. The best scientists combine active imaginations with a relentless search for truth and understanding.