How to fight online hate before it leads to violence

Research aims to thwart nasty online posts that can lead to real-world harm

Members of white-supremacist hate groups have been linked to the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021. FBI investigators found social media posts had helped draw people to coalesce as a mob with a call to “war.”

Samuel Corum/Stringer/Getty Images News

A rioting mob attempted an insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021. Social-media posts helped attract the participants to Washington, D.C., to take part. They included members of white-supremacist hate groups who came to challenge Joe Biden’s election victory.

Votes, recounts and court reviews established Biden’s clear win in the 2020 U.S. presidential election. But many social media falsely claimed that Donald Trump had gotten more votes. Some of those posts also urged people to flock to Washington, D.C. on January 6. They encouraged people to stop Congress from accepting the election results. Some posts discussed how to bring guns into the city and talked about going to “war.”

A rally with fighting words from Trump and others further stirred up the huge crowd. A mob then marched to the U.S. Capitol. After swarming through barricades, rioters forced their way inside. Five people died and more than 100 police officers sustained injuries. Investigations later linked members of white-supremacist hate groups to this insurrection.

Bigotry and hate are hardly new. But online websites and social media seem to have amplified their force. And, as events at the Capitol show, online hate can lead to real-world violence.

Outrage erupted last summer in Kenosha, Wis. Police had shot an unarmed man seven times in front of his children. The African-American man was the latest victim of excessive police force against Black people. Crowds gathered to protest the violence and other impacts of racism.

Unarmed Black people are more likely to be shot by police than unarmed whites. Yet some people pushed back against the protests. They portrayed protesters as criminals and “evil thugs.” Many social-media posts called on “patriots” to take up arms and “defend” Kenosha. These posts drew vigilante anti-protesters to Kenosha on August 25. Among them was a teen from Illinois who had gotten a gun illegally. That night, he and others carried weapons through the city. By midnight, the teen had shot three men. Police charged him for murder and other crimes. Yet some online posts called the killer a hero. And hateful posts against racial-justice protests continued.

These 2020 events are part of a long string of such incidents.

In 2018, for instance, a shooter killed 11 people at a synagogue in Pittsburgh, Penn. He had been active on the website Gab. It fed the man’s “steady, online consumption of racist propaganda,” according to the Southern Poverty Law Center. In 2017, a University of Maryland college student stabbed a visiting Black student at a bus stop. The killer was part of a Facebook group that stoked hate against women, Jewish people and African Americans. And in 2016, a gunman killed nine Black people at a church in Charleston, S.C. Federal authorities said online sources fueled his passion “to fight for white people and achieve white supremacy.”

But online hate doesn’t have to turn physical to hurt people. It can also cause psychological harm. Recently, researchers surveyed 18- to 25-year olds in six countries. Last year, they reported their findings in the journal Deviant Behavior. A majority said they had been exposed to online hate within the last three months. Most said they had come across the posts accidentally. And more than four in every 10 of the people surveyed said the posts had made them sad, hateful, angry or ashamed.

Civil rights groups, educators and others are working to combat the problem. Scientists and engineers are getting into the fight, too. Some are studying how online hate thrives and spreads. Others use artificial intelligence to screen or block hateful posts. And some are exploring counter-speech and other strategies as a way to fight back against hate.

How online hate spreads

Social-media sites can suspend or ban people who go against their rules for acceptable posts. But it’s not just a few individuals who are to blame here. “It’s more the collective behavior we see,” says Neil Johnson. He’s a physicist at George Washington University in Washington, D.C.

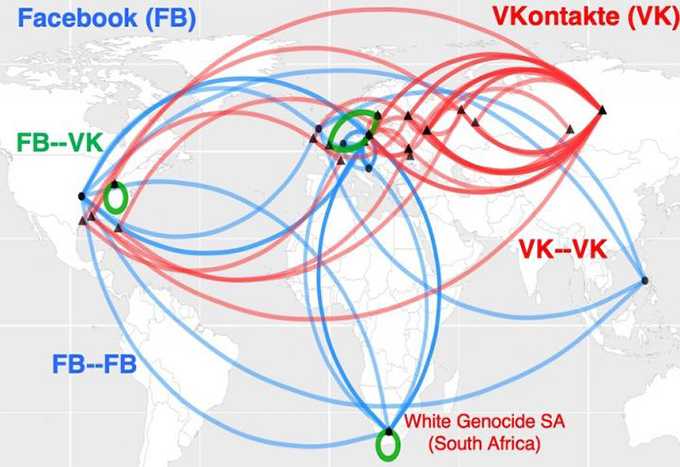

Johnson and others analyzed public data from different social-media platforms. Clusters of online hate seem to organize into groups, they found. Lots of different people post things in these groups. Posts also cross-link to other groups. Links between groups form networks between different social-media platforms.

In a way, he says, online hate is like a multiverse. That concept holds that other universes exist with different realities. Johnson likens each social media or gaming platform to a separate universe. The platforms have their own rules. And they operate independently. But just as some science-fiction characters might jump to another universe, online users can move to other platforms. If any one site clamps down on hateful or violent posts, the bad actors can go somewhere else.

Simply banning some bad actors, he concludes, won’t stop the problem. Johnson and his team shared their findings in the August 21, 2019 Nature.

Social-media platforms allow people to amplify the impact of hate. If celebrities share something hateful, for instance, they can expect many others will repeat it. Those others can create their own echo chambers with bots. Those bots are computer programs whose actions are meant to seem human. People often use bots to repeat hateful or false information over and over. That may make hateful ideas seem more widespread than they are. And that, in turn, can wrongly suggest that such views are acceptable.

Brandie Nonnecke heads the CITRIS Policy Lab at the University of California, Berkeley. Recently, she and others looked at the use of bots in posts about women’s reproductive rights. The team scraped, or gathered, a sample of more than 1.7 million tweets from a 12-day period. (She also wrote a plain-language guide for others who want to scrape data from Twitter for research.)

Both “pro-life” and “pro-choice” sides used abusive bots, as defined by Twitter policies. However, pro-life bots were more likely to make and echo harassing posts. Their words were nasty, vulgar, aggressive or insulting. Pro-choice bots were more likely to stoke divisiveness. They might take an us-versus-them stance, for example. The Institute for the Future published these findings in a 2019 report.

Screening out hate

Classifying hundreds of thousands of posts takes time, Nonnecke found. Lots of time. To speed up the work, some scientists are turning to artificial intelligence.

Artificial intelligence, or AI, relies on sets of computer instructions called algorithms. These can learn to spot patterns or connections between things. Generally, an AI algorithm reviews data to learn how different things should be grouped, or classified. Then the algorithm can review other data and classify them or take some type of action. Major social-media platforms already have AI tools to flag hate speech or false information. But classifying online hate isn’t simple.

Sometimes AI tools block posts that are not abusive. In March 2020, for example, Facebook blocked many posts that had been sharing news articles. The articles were not hate, lies or spam (unwanted advertising). Company leader Mark Zuckerberg later said the cause was a “technical error.”

Some AI errors can even backfire. “Algorithms do not understand language as we do,” notes Brendan Kennedy. He’s a graduate student in computer science at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. Often, an algorithm might “see the term ‘Black’ or ‘Muslim’ or ‘Jewish’ and assume this is hate speech,” he says. That could lead a program to block posts that actually speak out against bigotry.

“To develop algorithms that actually learn what hate speech is, we needed to force them to consider the contexts in which these social-group terms appear,” Kennedy explains. His group developed such an AI approach with rules. It makes its assessments of speech based on the way a term is used. He presented the method in July 2020 at a meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics.

Algorithms that just look for specific key words also can miss abusive posts. Facebook’s built-in tools didn’t block hateful memes about protesters and posts telling people to take up arms in Kenosha, for example. And after the killings, the platform didn’t automatically block some posts that praised the teen shooter.

When it comes to context, though, there still can be “a lot of uncertainty” about what category a post might fit into, says Thomas Mandl. He’s an information scientist. He works at the University of Hildesheim in Germany. Together with researchers in India, Mandl created “cyber watchdog” tools. They’re designed for people to use on Facebook and Twitter.

To label and screen hate speech, an AI algorithm needs training with a huge set of data, Mandl notes. Some human first needs to classify items in those training data. Often, however, posts use language meant to appeal to hate-group members. People outside the group may not pick up on those terms. Many posts also assume readers already know certain things. Those posts won’t necessarily include the terms for which the algorithms are searching.

“These posts are so short, and they require so much previous knowledge,” Mandl says. Without that background, he says, “you don’t understand them.”

In the United States, for example, Trump made a 2016 promise to “build the wall” along the U.S.-Mexico border. That phrase later became shorthand for nasty statements about refugees and other migrants. In India, likewise, online hate against Muslims often assumes readers know about the anti-Muslim positions supported by Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Mandl’s team made browser plug-ins that can scan posts in English, German and Hindi. It highlights passages in red, yellow or green. These colors warn if a post is openly aggressive (red), more subtly aggressive (yellow) or not aggressive. A user also could set the tools to block aggressive posts. The tools’ accuracy is about 80 percent. That’s not bad, Mandl says, given that only about 80 percent of people usually agreed on their ratings of the posts. The team described its work December 15, 2020 in Expert Systems with Applications.

Counter-speech

Counter-speech goes beyond screening or blocking posts. Instead, it actively seeks to undermine online hate. A response to a nasty post might make fun of it or flip it on its head. For example, a post might contrast #BuildTheWall with #TearDownThisWall. U.S. President Ronald Reagan used that second phrase in a 1987 speech at the former Berlin Wall in Germany.

Counter-speech probably won’t change the minds of online haters. But it points a finger at which online speech crosses the line into unacceptable language. And a new study suggests that organized counter-speech efforts might even reduce the amount of online hate.

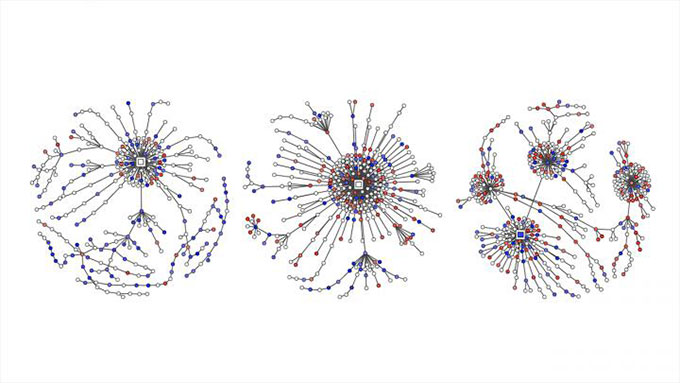

Mirta Galesic is a psychologist at the Santa Fe Institute in New Mexico. She and others examined online hate and counter-speech in Germany. They created an AI tool to detect both online hate and counter-speech. Then they trained their AI with millions of tweets from people linked to two groups.

The first group had 2,120 members of a hate-based organization known as Reconquista Germanica, or RG. The counter-speech group started with 103 core members of a movement called Reconquista Internet, or RI. For more data, the team added in people who actively followed at least five RI members. (The Twitter bios for those people also used language typical of RI members.) This brought the number of counter-speech accounts to 1,472.

“The beauty of these two groups is they were self-labeling,” Galesic says. In other words, people had made clear which group their own posts fell into. AI used what it learned in training with these tweets to classify other posts as hate, counter-speech or neutral. A group of people also reviewed a sample of the same posts. The AI classifications lined up well with those performed by people.

Galesic’s team then used the AI tool to classify tweets about political issues. That work involved more than 100,000 conversations between 2013 and 2018. The report was part of a Workshop on Online Abuse and Harms in November.

Galesic and her colleagues also compared amounts of hate and counter-speech on Twitter. Data came from more than 180,000 German tweets on politics from 2015 through 2018. Online hate posts outnumbered counter-speech in all four years. Over that time, the share of counter-speech did not increase much. Then RI became active in May 2018. Now the share of counter-speech and neutral posts increased. Afterward, both the proportion and extreme nature of hate tweets fell.

This one case study doesn’t prove that RI’s efforts caused the drop in hateful tweets. But it does suggest that an organized effort to counter hate speech can help.

Galesic compares the possible impact of the counter-speech posts to the way “a group of kids countering a bully in a real-life setting can be more successful than if it was just one kid standing up to a bully.” Here, people were standing up for the victims of online hate. Also, she says, you strengthen the case “that hate speech is not okay.” And by pushing out a lot of counter-hate tweets, she adds, readers will get the impression that crowds of people feel this way.

Galesic’s group is now investigating what type of individual counter-speech tactics might help best. She warns teens against jumping into the fray without giving it much thought. “There is a lot of abusive language involved,” she notes. “And sometimes there can also be real life threats.” With some preparation, however, teens can take positive steps.

How teens can help

Sociologist Kara Brisson-Boivin heads up research at MediaSmarts. It’s in Ottawa, Canada. In 2019, she reported on a survey of more than 1,000 young Canadians. All were 12- to 16-years old. “Eighty percent said they do believe it is important to do something and to say something when they see hate online,” Brisson-Boivin notes. “But the number one reason they did not do anything was they felt they didn’t know what to do.”

“You can always do something,” she stresses. “And you have a right to always do something.” Her group wrote a tip sheet to help. For example, she notes, you might take a screenshot of a hateful post and report it.

Suppose a friend posted something hurtful but you’re reluctant to speak out publicly. The MediaSmarts tip sheet says you can privately tell the friend that you feel hurt. If you think others might feel hurt by a post, you can tell them privately that you care and support them. And tell a parent or teacher if an adult you know posts something hateful. The tip sheet also suggests how to safely speak out publicly.

“Speaking out and saying something and pushing back encourages other people to do the same,” Brisson-Boivin says. For example, you can correct misinformation in a post. You can say why something is hurtful. You can change the subject. And you can always depart from a hurtful online conversation.

Sadly, online hate is not likely to soon disappear. But better computer tools and science-based guidance can help us all take a stand against online hate.