Analyze This: Some dogs quickly learn new words

Two dogs learned new words after hearing them a few times

Vicky Nina, one of two dogs shown to quickly learn new words, sits with a pile of her toys. Since many other dogs don’t seem to learn words easily, Vicky Nina may have a knack for new vocab. Researchers are investigating where that skill may come from.

Marco Ojeda

Sit. Stay. Roll over!

Our puppy pals can typically learn such commands with ease. Grasping the names of objects may present a tougher task for our canine companions. But there are exceptions. Some dogs learn toys’ names after hearing them only a few times, a new study finds.

As with young kids, “this learning doesn’t happen in the context of formal training. But it happens just during play,” says Claudia Fugazza. An ethologist, Fugazza studies animal behavior at Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest, Hungary.

Fugazza and her team found two dogs that already knew many words. Four-year-old border collie Whisky and nine-year-old Yorkshire terrier Vicky Nina each knew the names of around 50 objects, mostly toys. The scientists wondered how quickly the pooches could pick up new lingo.

The researchers tried two different ways to teach the dogs new words. In one (called the exclusion condition), the dogs had to pick out the new toy, such as a bulldog, from a group of known toys. After requesting a few known toys, the dog’s owner asked the pet to bring the bulldog. If the dog returned the right toy, it received praise and a treat. The owner repeated this with the second toy. In a second approach (called the social condition), owners would introduce the two new toys’ names while playing with their dog. They might toss one and say, “get the ladybug.”

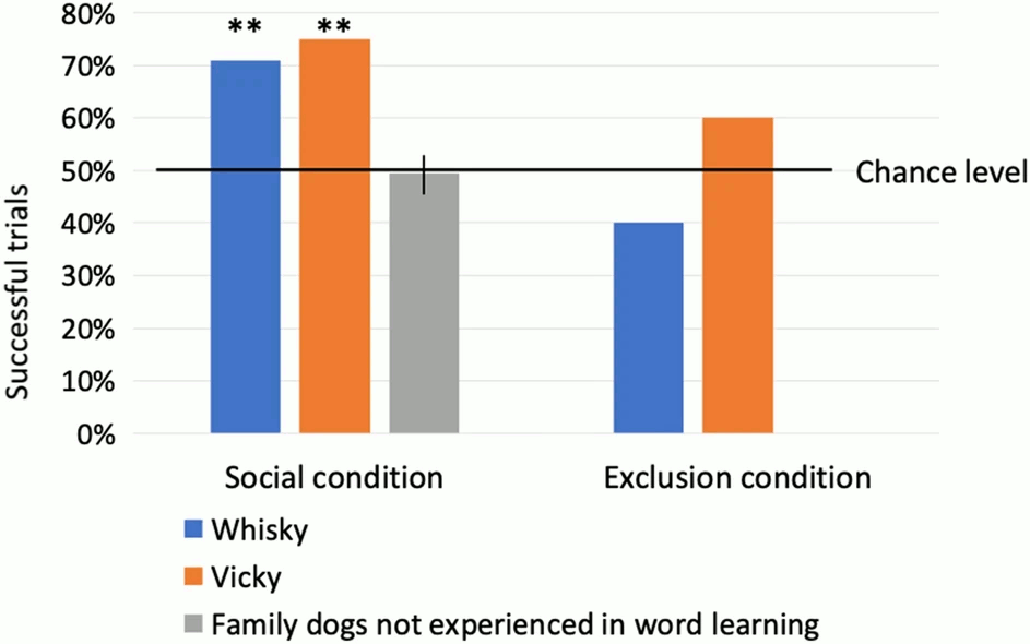

The team then tested each dog by placing the two new objects side by side in another room. The owner asked the dog to fetch one by its name to see if the animal brought the correct one. The dogs weren’t very successful when they had been taught the names through the exclusion condition. But after playing with the new toys, the dogs were much more successful. They had only four chances to hear the words, so the dogs’ quick learning was “impressive,” Fugazza says.

The knowledge didn’t stick for long, however. Vicky Nina and Whisky tended to forget the new word 10 minutes after passing the toy name test. Dogs may have to hear a word many more times to make a lasting memory. And even then not all dogs may be able to do this. Using the play approach, the team tried teaching another 20 pets who didn’t have experience learning words. These dogs faired more poorly when tested on their new words. The scientists shared their results January 26 in Scientific Reports.

It’s not clear why Whisky and Vicky Nina were good at picking up new vocab when other pets weren’t. This might be a talent that only some dogs have, Fugazza says. She and her team are investigating where word-learning skills may come from. The ability may also relate to hearing words early in a pup’s life, she says.

Data Dive:

- Look at the “exclusion condition” results on the right. What percentage of trials did each dog get right?

- If a dog is given two objects and asked to choose one, it should make the correct choice about 50 percent of the time based on chance alone. On the chart, 50 percent is marked as the “chance level.” How do the success rates of Whisky and Vicky Nina compare with this chance level in the exclusion condition? What does that mean for how well they learned new words?

- Now look at the “social condition” results on the left. What percentage did Whisky and Vicky Nina get right? How do these values compare with the chance level? And what does that mean for how well the dogs learned new words with this method?

- Why did the researchers not test family dogs in the exclusion condition?

- How do you think the results might change in each condition if the dogs heard the words more than four times during learning?