The HIV cure — that wasn’t

A toddler that appeared to have shed the disease continues to host it after all, doctors announce

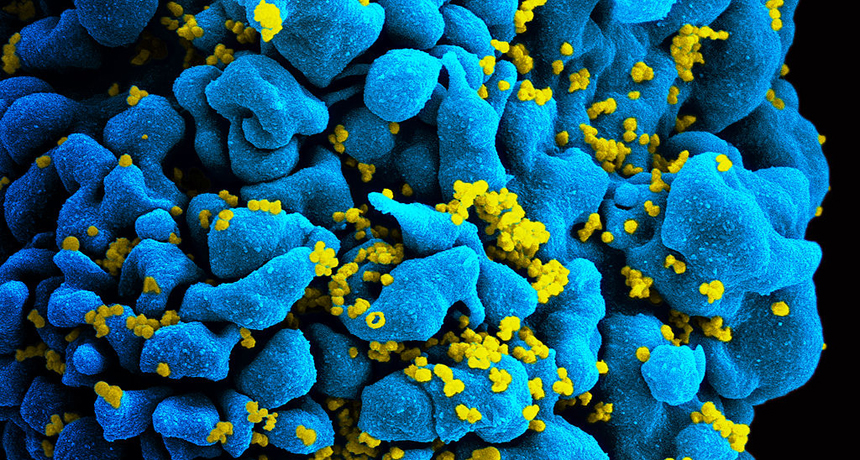

HIV shown here, in yellow, clinging to a T-cell, in blue. New tests of a baby that appeared cured of HIV, last year, show she is still infected.

NIH

By Janet Raloff

Last year, doctors in Mississippi reported that their treatment of a local baby had apparently cured the girl of HIV. She had been born with this virus, which causes AIDS. That initial report had sounded almost too good to be true. In fact, it was too good to be true. On July 11, doctors announced the girl remains infected with the virus.

“Certainly, this is a disappointing turn of events for this young child, the medical staff involved in the child’s care, and the HIV/AIDS research community,” said Anthony S. Fauci. A physician, he runs the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, in Bethesda, Md. The news “reminds us that we still have much more to learn,” he says. For now, he assured the public that the National Institutes of Health “remains committed to moving forward with research on a cure for HIV infection.”

HIV stands for human immunodeficiency virus. It kills cells in the body’s immune system. Those cells ordinarily defend us against infection. Once HIV cripples the immune system, the body cannot fight off germs — even those that don’t usually make people sick. When this situation develops, doctors say a patient has AIDS, meaning acquired Immune deficiency syndrome.

Since AIDS was first diagnosed in 1981, HIV has killed more than 35 million people. Each year, doctors diagnose another 2 million people with AIDS.

But HIV isn’t always a death sentence. New treatments are allowing many infected people to live a normal lifespan. Still, the goal remains a cure. And that’s what made last year’s announcement so exciting. Doctors had given the baby a trio of anti-virus drugs for 18 months. They started when she was just 30 hours old. That’s far earlier than had ever been tried before.

The virus showed up in her blood for a month. But after that, the infectious virus disappeared. And the girl’s blood remained clear of infectious virus until her family moved away. At that point, the baby’s treatment stopped. Recently, doctors were able to test the girl again. She is now almost four years old. During one test, her blood had 16,750 copies of HIV per milliliter (or 553 copies of the virus per ounce). Three days later, doctors tested her again. This time she had 10,564 copies of HIV per milliliter of blood. So the new finding of substantial HIV had not been a mistake.

T-cells are a type of white blood cell. They act like security patrols for the human immune system. As soon as they detect “intruders” — such as bacteria or viruses — they dispatch warning signals. Those signals are a call to act, and normally the body responds by sending out special cells. These will attack the invaders. When those invaders are HIV particles, the T-cells that go on alert are known as CD4 cells.

In people with HIV, the armies of helpful CD4 cells will eventually start to fall. When they get too low, doctors usually begin prescribing anti-HIV drugs.

CD4 levels in the Mississippi preschooler are low, Fauci reported last week. That signals that HIV is actively reproducing in her body. So doctors have started giving the girl anti-virus medicines again.

The good news: The very early drug therapy seems to have given this girl a helpful edge in fighting the virus. Indeed, the fact that virus levels remain fairly low despite the girl receiving no drug therapy for two years “is unprecedented,” says Deborah Persaud. She’s a physician and infectious disease specialist at the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center in Baltimore, Md. She also was one of the children’s HIV experts who had followed the Mississippi baby’s treatment. “Typically,” Persaud says, “when treatment is stopped, HIV levels rebound within weeks, not years.”

The prompt and aggressive HIV treatment given to the baby limited how fast her disease developed, Fauci now suspects. It also reduced her need for medicine. “Now we must direct our attention to understanding why that is,” he says. His team also wants to find out, he says, if holding virus levels low “in the absence of therapy can be prolonged even further.”

Power words

AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) A disease that weakens a body’s immune system, greatly lowering resistance to infections and some cancers.

CD4 cells A type of white blood cell — called T cells — that scout for viral invaders such as HIV.

HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) A potentially deadly virus that attacks cells in the body’s immune system and causes acquired immune deficiency syndrome, or AIDS.

immunity The ability of an organism to resist a particular infection or poison by producing and releasing special protective cells.

infection The successful invasion of a disease-causing microorganism into the body, where it multiples, possibly causing serious injury to tissues (such as the skin, lungs, gut or brain).

T cells A family of white blood cells, also known as lymphocytes, that are primary actors in the immune system. They fight disease and can help the body deal with harmful substances.

virus A tiny molecule made of a protein shell that encloses genetic information. A virus can live and multiply only in the living cells of a host organism, such as people.