How schools can reduce excessive discipline of their Black students

Keeping Black children in school requires changes to both systems and mind-sets

U.S. educators punish Black students more frequently and severely than white students. This discipline gap may help to explain why Black students, on average, score lower on standardized tests than white students.

monkeybusinessimages/iStock/Getty Images Plus

By Sujata Gupta

Anne Gregory remembers the boy’s fondness for the Dewey decimal system. He would write down a combination of numbers and letters on a scrap of paper. Then he would hunt down the desired book in the library. Details were his thing. He once wrote a multipage memo outlining the sequence of moves needed to beat a video game, she says.

But at the elementary school where Gregory worked as a counselor, teachers saw a different child. A troublemaker. One of them told Gregory that this boy often wandered about mid-lesson. So the teacher moved his desk to the far corner of the room. Sometimes he was sent to the principal’s office.

Outside the principal’s door, the child joined a line of boys. Almost all were Black, as he was, even though Black and Latino students together made up only slightly more than half the student population. Gregory brought up her concerns with the principal. Why was that little boy always in trouble? Why were most of the supposed troublemakers Black and male?

This was back in the mid-1990s. It was a time when teachers and researchers had started looking into why Black students, on average, scored lower on standardized tests than white students did. They called this the “achievement gap.” And it had become a concern. But how teachers treated Black children rarely was part of the discussions. The principal told Gregory that her concerns were potentially valid. However, they were “too hot” to tackle.

“I could just see how much the school structure itself was squelching this African American boy’s potential and all his strengths,” Gregory says. “That, accompanied with the silence around this at his school, demonstrated to me the absolute urgency — the need — to point this out.”

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

Gregory is now a psychologist at Rutgers University. It’s in Piscataway, N.J. She has devoted her career to pointing out the problem. In the January 2010 Educational Researcher, she used the term “discipline gap” to describe what she’d seen. Black students, particularly boys, were punished more often and severely than their white peers. That was true even when kids committed the same offenses. The punishments ranged from being sent to the principal to expulsion. The higher rate at which Black students were removed from school may well underlie the achievement gap, Gregory now argues.

Over time, changes to laws and to school policies have narrowed that discipline gap. For instance, many school districts no longer allow suspensions for minor offenses. Talking back to a teacher no longer will get a kid kicked out of school. Still, a gap remains. Black students in middle and high school were four times as likely to be suspended as were white students during the 2015–16 school year. That number comes from an October 11, 2020 report. It was prepared by the Civil Rights Project, based in Los Angeles, Calif.

Policy changes alone cannot close the gap, concludes Russell Skiba. He’s a school psychologist at Indiana University Bloomington. Teachers also must transform how they view Black students. Changes that reduce suspensions and expulsions are needed. But so is a “focus on issues of implicit bias [and] structural racism,” Skiba says. Implicit bias is an unrecognized preference for or prejudice against something. “Structural racism” is a term for all of the ingrained policies and practices that can oppress people of color.

Removing Black students from the classroom robs them of a lifetime of opportunities, adds Daniel Losen. He directs the Center for Civil Rights Remedies at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). He also coauthored the October 11 report. Compared with other students, punished students are more likely to fall behind academically, often by years. They may have lower test scores. Some drop out of school. In the end, they may earn less and end up in prison. “This is a massive civil-rights violation,” says Losen.

Punishing practices

Punishment practices in U.S. schools are nothing new. Take the Gun-Free Schools Act of 1994. It requires the expulsion for at least one year of any student who brought a weapon to school. No hearing necessary.

Additional zero-tolerance laws followed. These included mandatory suspension or expulsion for minor or technical offenses. Since then, students have been removed from school for wielding such “weapons” as nail clippers or rubber bands. Some have been kicked out for distributing “contraband” cough drops.

Unequal burden

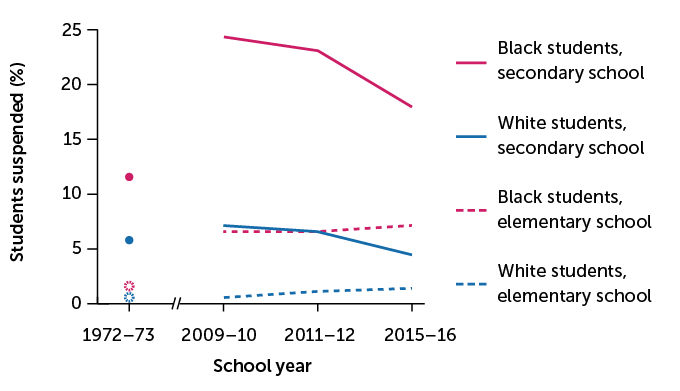

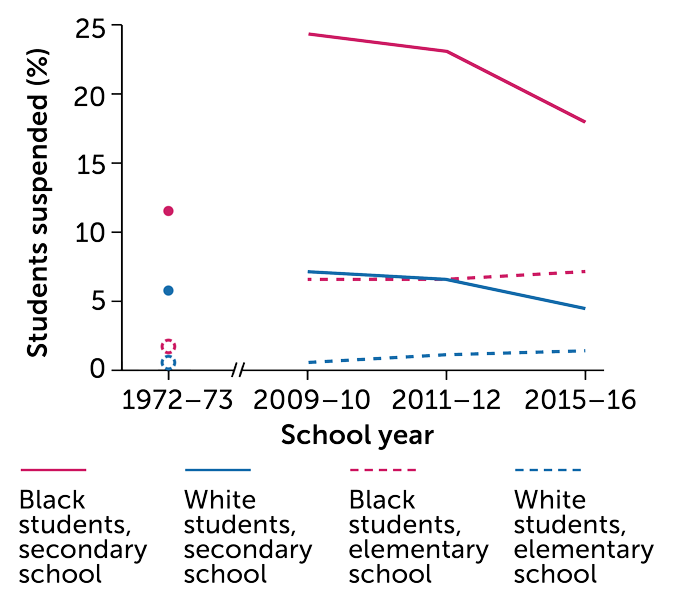

Although suspension rates of U.S. middle and high school students have been dropping, the gap between Black and white students has changed little, federal data show. Elementary school rates are lower, but rising for Black children.

U.S. school suspension rates by race, 1972-2016

Zero-tolerance policies account for about one tenth of the racial-discipline gap. That’s according to Chris Curran. He reported it a little over four years ago in Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. Curran is an educational-policy expert of the University of Florida in Gainesville.

The explicit or implicit biases of teachers against Black children also keep the gap wide. Those biases show up as early as preschool. In one study, researchers fit 135 early-education teachers with eye trackers. These teachers then watched video clips of four kids seated around a table — a Black girl, a Black boy, a white girl and a white boy. The researchers told the teachers to look for misbehaviors.

In truth, none of the children misbehaved. The eye trackers, though, revealed that the teachers’ focused on the Black boy. When later asked which child required the most attention, 42 percent chose the Black boy. Another 34 percent chose the white boy, 13 percent chose the white girl and 10 percent chose the Black girl. Yale University researchers reported this to federal and state officials in September 2016.

Another study shows how such bias contributes to harsher discipline for Black students. Researchers asked 191 teachers of classes from kindergarten through high school to imagine teaching at a middle school depicted in a photo. The teachers then read a series of stories about a student who got into trouble twice. In one story, the student got in trouble for not following rules or for disrespecting authority figures at school. In another, the student disrupted class. Researchers told half the teachers that the student’s name was Darnell or Deshawn. These are stereotypically Black male names. The other half of the teachers were told that the boy was named Greg or Jake. These are stereotypically white male names.

After each incident, the teachers answered questions on a five-point scale. For instance, “How severe was the student’s misbehavior?” And “How severely should the student be disciplined?”

After the first bad behavior, the teachers were equally lenient toward the Black and white boys. But after the second bad behavior, the teachers rated Black boys as 25 percent more troublesome than white boys. They also recommended 30 percent harsher discipline. The researchers reported this in 2015 and called their finding the “two strikes” paradigm (PAIR-uh-dyme).

That study shows how bias can show up in institutions, says Sean Darling-Hammond. He’s a graduate student in education policy at the University of California, Berkeley. After repeated misbehaviors, teachers still forgave white kids but not the Black ones.

Color-blind corrections

The Civil Rights Project’s October 11 report provides the most up-to-date snapshot of the discipline gap. Its data come from the Civil Rights Data Collection of the U.S. Department of Education. These data describe student enrollment, demographics and discipline in every major U.S. school district.

Overall suspension rates fell between the 2009-10 and 2015-16 school years. Suspension rates for kindergarteners through 12th graders fell from 4 percent to 3 percent for white students. They dropped from 16 percent to 13 percent for Black students. Throughout, Black students still were suspended at four times the rate of white students.

Kenneth Shores studies educational policy at the University of Delaware in Newark. No school policy can deal with all the differential treatment of kids at school, he says. That includes common situations. One example is when teachers praise white students while criticizing Black students. Or when they primarily call on white students in class.

But many current actions taken to improve the school climate sidestep issues of race. For instance, several programs rely on “restorative justice.” That brings victims and offenders together to discuss an incident. It gives all parties a voice. This approach is often used in criminal-justice settings.

Restorative justice can help teachers change how they cope with classroom issues. In schools, it also can build trust and open communications. It often is used instead of discipline.

For instance, many schools use a multi-tier system of support for students and staff. Tier one is prevention. Students come together in so-called community-building circles. They discuss a prompt or a question. Then they listen to each other’s perspectives. At tier two, students involved in a minor dispute work together in “responsive circles.” Those circles work to solve the problem. At tier 3, everyone involved in a serious dispute takes part in a “restorative conference.” Here, a trained guide moderates the discussions. If a student is still suspended, educators later welcome the student back to school. They then gauge if that student needs more support to get caught up on classes.

This has been tried in Denver, Colo. As of 2017, more than 2,500 teachers had been trained to lead these types of circles. In 2006, Denver’s suspension gap between Black and white students had been 12 percentage points. About 6 percent of white students had been suspended compared with 18 percent of Black students. By 2013, the gap had narrowed to 8 percentage points. Researchers described the improvement in Closing the School Discipline Gap, a book Losen coedited.

But schools were still suspending more Black students than white students. In effect, the color-blind approach worsened the racial-suspension gap. It went from a three-fold difference between Black and white students to an almost five-fold one now.

Addressing race

Decades have passed since Gregory observed that young boy waiting outside the principal’s office. And she is still working to help children like him.

Two years ago, for instance, Gregory and her colleagues piloted a program to confront racism in schools. They tested it at one elementary, one middle and one high school in New York City. The program combines a race-conscious version of restorative justice. It also helps kids learn ways to control their emotions. It teaches self and social awareness. It also works on responsible decision-making.

During 25 hours of training, teachers come together in circles similar to those used in Denver. The prompt, however, asks teachers to consider how structural racism hurts children. After that initial training, teachers also get one-on-one coaching.

These moderated discussions around race have helped teachers speak freely about their worries, Gregory has noted. For instance, during the training circles, teachers often express concern that approaches without punishment are too soft or lack structure. When that happens, Gregory and her colleagues walk teachers through ways to respond differently when kids misbehave.

Data collection, too, is key to making such a new program work, Gregory says. Those data can help point out any disparities. For example, the pilot middle school in Gregory’s study had mostly Black students. So racial gaps in discipline had been less of a problem there to start with. School officials knew, however, that girls misbehaved more than boys. Yet, when school officials looked at the data, they found teachers had been punishing boys more and more severely than girls.

The COVID-19 pandemic interrupted this two-year pilot project, Gregory says. But its early results appear promising. And her team has begun scaling up the program at 18 more New York City schools. The researchers also are monitoring how school leaders provide support. This might be creating space for restorative circles. Or they might free up time so students can practice controlling their emotions.

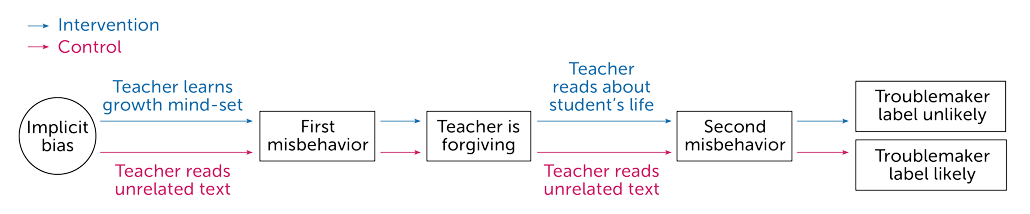

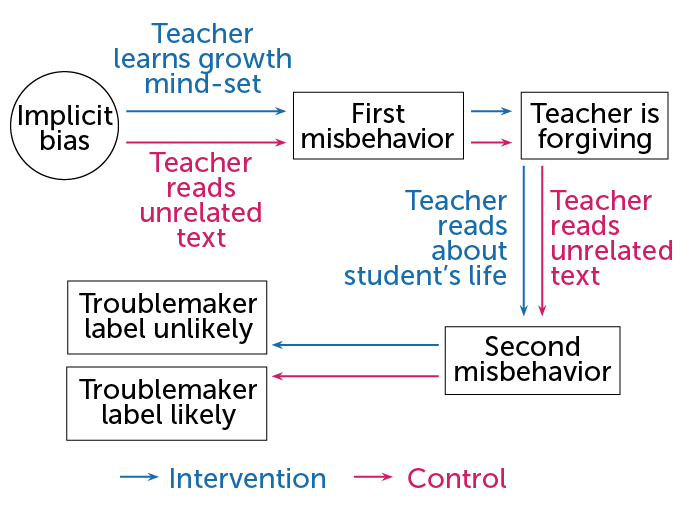

Unfortunately, efforts to eliminate people’s biases rarely stick, research shows. So rather than targeting the bias itself, Darling-Hammond at Berkeley and his colleagues recently tried addressing its downstream impacts. That is, if harsh discipline begins with bias and ends with, say, expulsion, then what between those two points might be easier to change? The team identified two things: how teachers view a child’s ability to change and getting to know those students better.

The two-strikes work from 2015 showed that educators were quick to label Black students as troublemakers. So Darling-Hammond’s team wondered if it could convince teachers to adopt a “growth mind-set.” This is the belief that their students can change. The team also theorized that once teachers came to believe “bad” students could become “good,” teachers would need more time and space to get to know those kids.

Following up on the 2015 study, these researchers asked a different group of U.S. teachers to read accounts about a hypothetical student. He was named either Deshawn or Jake. But this time teachers got extra descriptions about these “students.” First, about half of 243 teachers read a passage on the growth mind-set. It described how teachers can change a student’s life. Then they read about Deshawn’s or Jake’s first misbehavior. That was followed by a third account. This one described the student’s love of music and struggles outside of school. Last, the researchers read about the student’s second misbehavior. Then the teachers answered questions on a five-point scale.

Yet another group of teachers, part of a “control” group, read only the misbehavior accounts. That was interspersed with readings about how technology enhances student engagement or journaling.

Teachers who read the additional accounts rated Deshawn and Greg the same on all measures. This included whether the student was a troublemaker and the severity of discipline required. It also included how likely it was that this student would get suspended in the future. Put simply: The racial differences the researchers observed in 2015 disappeared.

The team reported its findings October 16 in Science Advances. The next step, says Darling-Hammond, is to see if the same approach works in situations with real kids, not hypothetical ones.

Course correct

Research suggests teachers are more lenient with white students than Black students — a sign of implicit bias. One new study taught teachers how students and relationships can improve. The teachers also learned more about the students. Afterward, these teachers labeled Black students as troublemakers less often than did teachers who read unrelated text.

Testing the growth mind-set

The virtual classroom

Losen and others worry that the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic could make shrinking the discipline gap harder. Data collected during the pandemic are not yet available. But anecdotes of teachers punishing Black students for misbehaving during online classes have recently turned up.

Police arrived at the home of one 12-year-old in Colorado after his art teacher saw him playing with a neon green toy gun. Emblazoned across it was the term “zombie hunter.” The school later suspended the boy for five days.

Police also visited a boy in New Jersey after a teacher saw him playing with a Nerf gun. School officials in Louisiana suspended a 9-year-old boy for having an unloaded BB gun visible in his bedroom.

During this pandemic, teachers have even less time and opportunity to get to know what’s going on in their students’ lives. And everyone’s stress level is at an all-time high, Losen says. “Unless we do something very different and really address needs in a way that we never have, we’re going to see a train wreck.”