Scientists discover likely source of the moon’s faint yellow tail

Debris gets kicked up from the lunar surface, mostly by micrometeorite impacts

Most material in the moon’s comet-like tail of sodium atoms, not seen here, were boosted off the moon by micrometeorite impacts, new studies suggest.

Joel Kowsky/NASA

By Sid Perkins

A comet-like tail of sodium atoms streams away from the moon. Over the years, scientists have proposed various ideas for how that sodium got there. Two new studies now pin down a likely source for most of it: swarms of small meteorites that constantly bombard the moon.

First discovered almost 23 years ago, the tail was eventually shown to be a flood of atoms coming off the moon. But what was releasing them remained a mystery.

Some scientists had suggested sunlight striking lunar rocks could give sodium atoms enough energy to escape. Others proposed that the solar wind — charged particles streaming from the sun — might be knocking sodium atoms from the rocks. Even charged particles emitted by the sun during intense solar flares might do this. And then there were those micrometeorites. They might liberate sodium as they crashed into moon rocks. That sodium might even come from the meteorites themselves.

Jeffrey Baumgardner is a space scientist in Massachusetts. He was part of a Boston University team that decided to try to resolve the mystery.

The team looked at images of a brighter-than-normal part of the tail taken from an observatory in Argentina between 2006 and 2019. That period is longer than a complete 11-year cycle of sunspot activity. So the images should have been able to detect any link between the tail’s brightness and changes in the solar wind or solar flares. In fact, no such links emerged.

What did show up was a tie between the brightness of the sodium tail and meteor activity. The Earth and its natural satellite should experience the same meteor activity, Baumgardner points out. But while Earth is largely shielded by a thick atmosphere, the moon’s atmosphere is too thin to keep most micrometeorites from reaching the surface.

The Boston group described their findings in the March Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.

Accidental discovery

Scientists first stumbled onto the tail while “looking for something else,” Baumgardner recalls.

It happened right after the Leonid meteor shower in 1998. This shower recurs every mid-November. Researchers were watching on November 17 to see if tiny meteorites burning up in the atmosphere were seeding the thin upper air with sodium atoms. In fact, they weren’t. But on the next three nights, the team’s instruments did spy a faint patch of light in the sky. That blobby patch glowed with the yellow hue of sodium atoms. It covered an area about six times wider than the moon appears. By the fourth night, this glow had disappeared.

But the yellow spot returned regularly in the following months. Each time it showed up within a day or so of a new moon. That’s when the moon is almost directly in between the Earth and sun. Plus, the glowing spot always showed up almost directly on the opposite side of Earth to where the sun and moon were. And its brightness varied some. These were big clues to its origin, Baumgardner says.

Eventually, researchers figured out that the spot was made of atoms of sodium that had been blasted into space from the moon. The sun’s light and solar wind then pushed the sodium tail away from the sun, just as they push away a comet’s tail. Periodically, Earth sweeps through this tail. As this happens, Earth’s gravity focuses this tail behind our planet. That’s when the tail is close enough and bright enough for telescopes to detect. Astronomers have dubbed this concentrated part of the tail the “sodium moon spot.”

Explanation finds support

The new findings “are really neat,” says Jamey Szalay. He’s a space scientist at Princeton University in New Jersey. “[Baumgardner’s group] looked at a ton of data collected over a very long time,” he notes.

Baumgardner suspects the large data set that his team analyzed may have made a big difference. Previous studies had used data collected over shorter periods. And they turned up no link between spot brightness and random meteorite activity over the years.

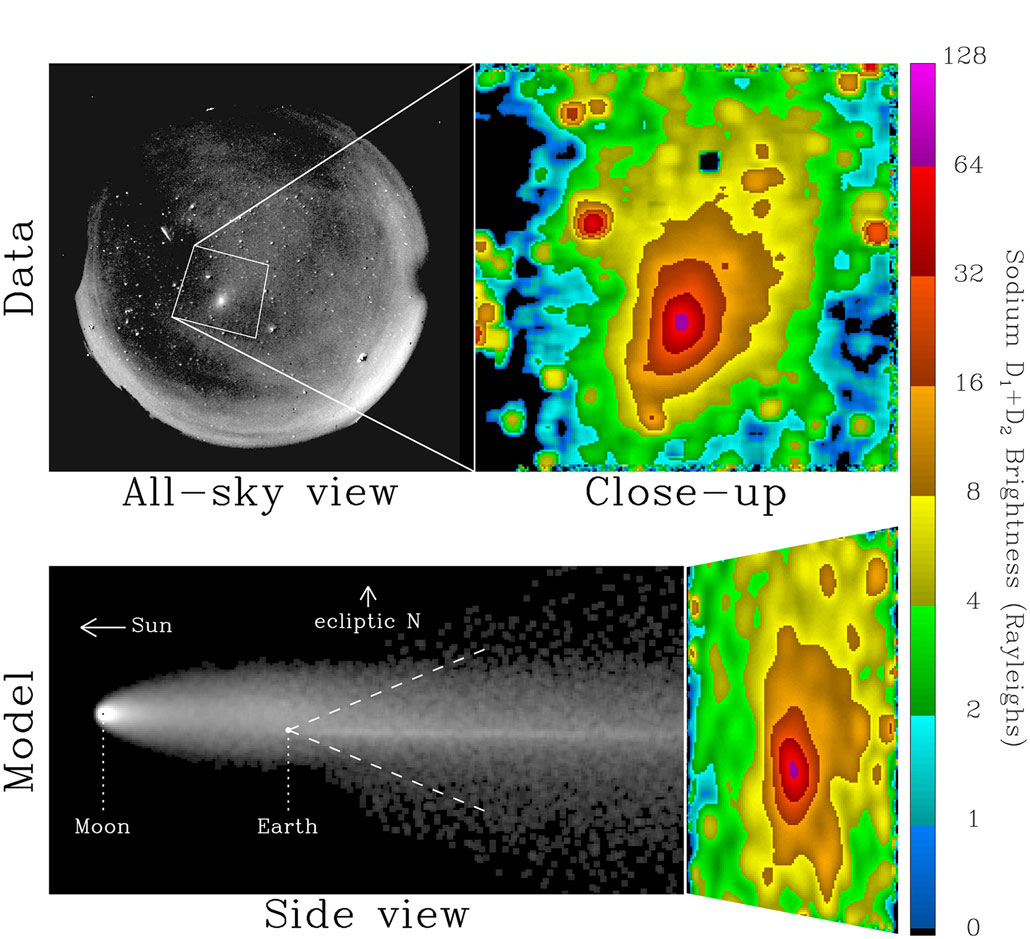

Results of the new analysis are backed by a second new study. This one looked at the sodium moon spot in a different way. As atoms in the tail move through the sodium spot that’s visible from Earth, they travel at about 12.4 kilometers per second (nearly 28,000 miles per hour). Researchers at Kyung-Hee University in Yongin, South Korea wanted to see what mix of sodium sources could produce atoms travelling that fast.

For answers, they turned to a computer model. It simulated the speeds of sodium atoms that sunlight would free from lunar rocks. It also modeled what the speeds would be of sodium atoms bumped off the moon by the solar wind and or by solar flares. Finally, the model simulated the speeds of atoms spewed when micrometeorites crashed onto the moon.

The model predicted atoms from all three sources would be in the lunar tail. But the largest number would come from micrometeorite impacts. The researchers described their analysis March 5 in Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics.