Europe’s ancient humans often hooked up with Neandertals

By about 45,000 years ago, the two species had interbred fairly often

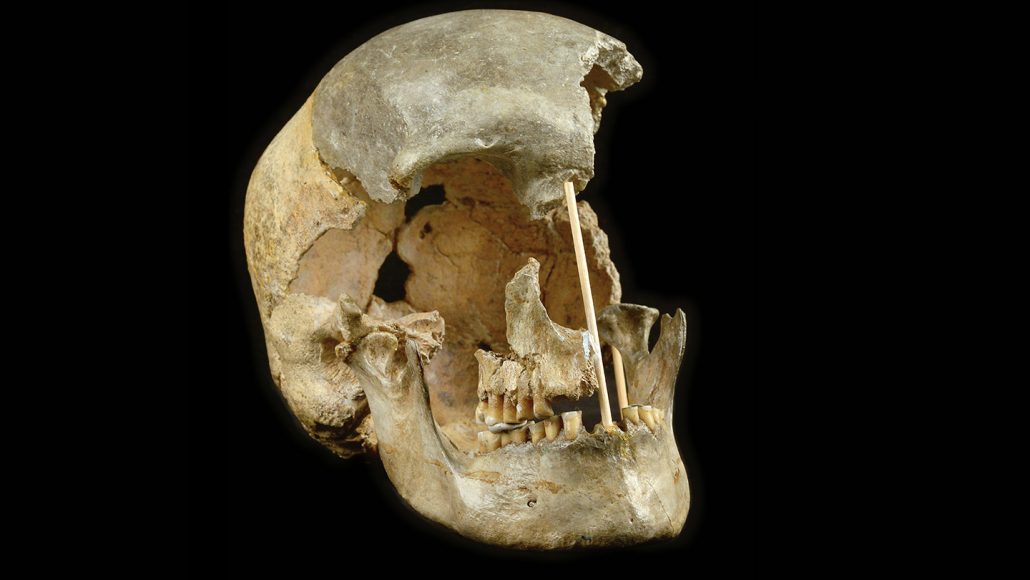

This is the skull of a woman who lived more than 45,000 years ago in what is now the Czech Republic. Her DNA shows that the population she lived in bred frequently with Neandertals.

Marek Jantač

By Bruce Bower

When early humans arrived in Europe around 45,000 years ago, they found Neandertals already there. So they hooked up with them. Those hookups between Homo sapiens and Neandertals happened more often than scientists had been assumed. That’s the conclusion of two new studies.

Scientists analyzed ancient DNA from a tooth and two bone fragments. They were the remains of three people unearthed in the Bacho Kiro Cave in Bulgaria. The bone bits had been radiocarbon dated. This process can determine the age of once-living tissue.

The bones’ owners lived 43,000 and 46,000 years ago. That makes them the oldest known human remains in Europe. Stone tools typical of late Stone Age humans were found in the same soil as the fossils. With the DNA still inside the bone remains, scientists showed that Neandertals contributed about 3 to 4 percent of the humans’ DNA.

“All of the Bacho Kiro individuals had recent Neandertal ancestors, as few as five to seven generations back in their family trees,” says Mateja Hajdinjak. She is an evolutionary geneticist. That’s someone who studies DNA to learn about human evolution. She works at the Francis Crick Institute in London, England.

A second study shows further evidence of ancient interbreeding. Scientists turned it up a nearly complete human skull in 1950. They found it in a cave in what’s now the Czech Republic. A new analysis of its DNA shows it came from a female. Her DNA suggests she also lived around 45,000 years ago. And about 2 percent of her genes come from Neandertals, say Kay Prüfer and his colleagues. Prüfer is an evolutionary geneticist. He works at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany.

These human fossils aren’t the first ones found with bits of Neandertal DNA. But they appear to be the oldest. These data show for the first time that distinct human populations reached Europe fewer than 50,000 years ago. Neandertals interbred with all the groups detected so far. Some of their genes live on today in our DNA. Hajdinjak’s findings were published April 7 in Nature. Prüfer’s findings appeared April 7 in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

Neandertals went extinct around 40,000 years ago. But some of their genes live on in humans. Nearly 2 percent of the DNA, on average, in non-African people comes from Neandertal ancestors. Present-day Africans have about 0.5 percent Neandertal DNA.

The new studies also suggest that some early human entrants to Europe had a long-lasting impact on our DNA. Others hit genetic dead-ends. The Bacho Kiro people represent a newly identified group of ancient Europeans. They have genetic ties to present-day East Asians and Native Americans. But they aren’t linked to western Eurasians, Hajdinjak’s group says. The Czech Republic woman’s line, on the other hand, ended about 40,000 years ago. People today have inherited no genes from her descendants.

“It is remarkable that the Bacho Kiro finds could represent a population that was spreading 45,000 years ago, at least, from Bulgaria to China,” says Carles Lalueza-Fox. He’s an evolutionary geneticist who works at the Institute of Evolutionary Biology. It’s in Barcelona, Spain.

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

Other people who reached Europe thousands of years later were the ancestors of today’s Europeans, Hajdinjak suggests. At Bacho Kiro Cave, for instance, there is DNA from another newly recovered human-bone fragment. It only dates to around 35,000 years ago — the Stone Age. This newer bone displays different DNA than that of the cave’s earlier residents. This Stone Age person contributed genes mainly to Europeans and western Asians, Hajdinjak says.

By nearly 40,000 years ago, Neandertals were headed for extinction. This means that a fairly large number of incoming humans were breeding with a small number of Neandertals, Lalueza-Fox suspects.

More recently than 40,000 years ago, new human migrants into Europe would mate with the people already there. But those new people would have little or no Neandertal ancestry. Over time, they would have diluted Neandertal DNA from the human gene pool down to the small amounts that remain today, he says.