Sudden shark die-off 19 million years ago eliminated most species

New fossil evidence shows 90 percent of sharks died in the mysterious event

Shark species found in today’s oceans, such as this scalloped hammerhead, are far fewer than existed before a mysterious extinction event some 19 million years ago.

Gerard Soury/The Image Bank/Getty Images

Massive numbers of sharks died abruptly 19 million years ago, new data show. Fossils from sediments in the Pacific Ocean reveal that 90 percent of them vanished. And so far, scientists don’t know why.

“It’s a great mystery,” says Elizabeth Sibert. She led the new study. A paleobiologist and oceanographer, she works at Yale University. That’s in New Haven, Conn. “Sharks have been around for 400 million years. And yet this event wiped out [up to] 90 percent of them.”

Sharks have suffered losses in the past. It started 250 million years ago during the Great Dying. This event marked the end of most large ocean species. Much later, about 66 million years ago, a huge asteroid fell to Earth. It killed off most dinosaurs — and 30 to 40 percent of shark species. After that, sharks enjoyed about 45 million years as the ocean’s top predator. They even survived large climate disruptions, such as an episode about 56 million years ago when global levels of carbon dioxide spiked and temperatures soared.

The newly discovered fossils are a surprising twist in the shark’s story.

Sifting sediment

Sibert sifted through fish teeth and shark scales in the sediment. She worked with Leah Rubin, a student at the College of the Atlantic in Bar Harbor, Maine. Scientists had collected that sediment during various expeditions to the North and South Pacific oceans. “The project came out of a desire to better understand the natural background variability of these fossils,” Sibert explains.

Sharks’ bodies are mostly cartilage. Unlike bone, cartilage is difficult to preserve as fossils. But sharks’ skin is covered in tiny scales. Each scale is about the width of a human hair follicle. These scales make for an excellent record of past shark abundance. They contain the same hard mineral as sharks’ teeth. Both can turn to fossils in sediments. “And we will find several hundred more [scales] compared to a tooth,” Sibert explains.

What her team discovered was a surprise. From 66 million to about 19 million years ago, the ratio of fish teeth to shark scales held steady at about 5 to 1. Then the ratio took a dramatic turn: 100 fish teeth appeared for each shark scale. The team estimates this change was abrupt — within 100,000 years or so.

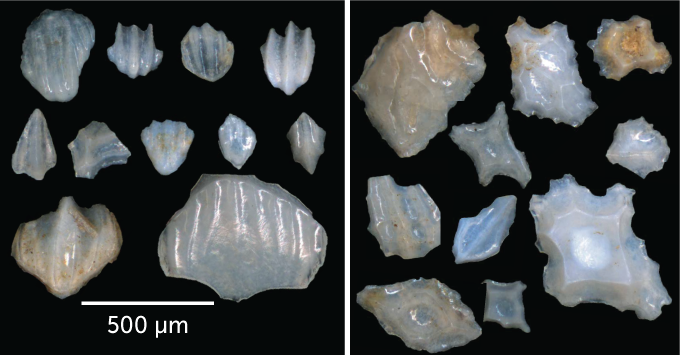

That sudden disappearance of shark scales came at the same time as a change in the scales’ shapes. This provides clues about shark diversity.

Most modern sharks have lined grooves on their scales, ones that may help them swim faster. Other sharks’ scales have geometric shapes. The researchers looked at the change in the abundance of various scale shapes before 19 million years ago and then again afterward. This revealed a huge loss in shark diversity. It appears some seven in every 10 shark species went extinct.

And this extinction event was quite “selective,” notes Rubin. After the event, the geometric scales “were almost gone.” And that previous diversity in sharks, she adds, was never seen again. She and Sibert describe their findings June 4 in Science.

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

A cautionary tale

An explanation for the massive shark die-off isn’t obvious, Sibert says. “Nineteen million years ago is not known as a formative time in Earth’s history.” Solving the mystery is one question she hopes to answer. She wants to understand how the varied scale shapes might relate to shark lineages. She’d also like to learn what impact the sudden loss of so many big predators might have had on other ocean dwellers.

Answers to those questions could be helpful today. Overfishing and ocean warming in the last 50 years have decreased shark populations by more than 70 percent. This loss of sharks no doubt impacts the ocean’s ecology.

Catherine Macdonald is a marine conservation biologist at the University of Miami in Florida. She sees the study as a cautionary tale. “Our power to act to protect what remains does not include an ability to fully reverse or undo the effects of the massive environmental changes we have already made,” she notes.

What happens to communities of the ocean’s top predators can be critical signs of those changes. Unraveling how the ocean ecosystem responded to shark losses in the past could help researchers predict what may await us now, Sibert says. “The sharks are trying to tell us something,” she explains, “and I can’t wait to find out what it is.”