Stores and malls buy into ponds and rain gardens for flood control

Extra bonus: These rainy-day ponds clean up dirty water

Anne Jefferson stands by a retention pond behind a strip mall. These ponds hold runoff from the stores and parking lots. Some even filter the water, so that it enters streams and lakes clean.

Elisabeth Lynne

Next time you go to a mall or a large chain store, such as Walmart, take a look around. Beside the parking lot you may find a pond. Its purpose is not to make the stores look nicer, although the water may indeed look pretty. These ponds are there to help manage water that flows off parking lots when it rains.

Anne Jefferson works at Kent State University in Ohio. There she studies water as it moves through the environment. Of urban rain gardens, she notes, “Once you start looking for them, you can see them all over.”

Rain is mostly clean, she points out. The ground isn’t. When rain hits the ground, it picks up pollutants. “Every time we brake [a car], we are shedding tiny bits of metal onto the street,” she says. Pollutants left behind by nearby industrial activities, traffic or more also taint the pavement.

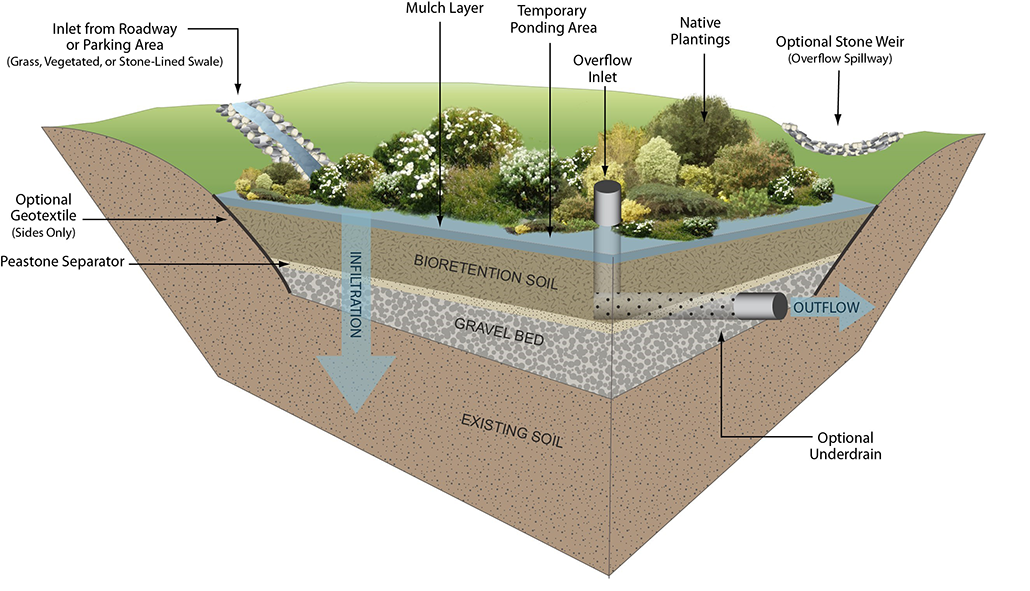

If rainwater goes directly from a street into a storm drain, it can bring those pollutants with it. But if the water passes through something called a bioretention cell, it might come out cleaner, Jefferson says. These holding cells also have a much more charming name: urban rain gardens. Some always hold water. Others look like a big ditch or low-lying field. After major downpours, they start filling with water that runs off of streets, parking lots or industrial sites.

Water helps plants grow. But too much can lead to flooding, which is never good for cities. A rain garden’s low-lying fields can “slow the flow” of rains, Jefferson notes. They temporarily store the water running off parking lots, roofs and streets. Later, she says, these so-called ponds can slowly release that water into a stream. In this way, she explains, they help reduce flooding. In some cases, she notes, cities or industrial plants will try “to soak up the water so that it doesn’t get to the stream at all.”

That’s why many cities and businesses are adopting these rain-collection sites, Jefferson says. Keep your eye peeled, she says. Nearly anytime you visit a Walmart, she says, there’ll be “a pond in the parking lot someplace off to the side.”

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

These ‘gardens’ clean up pollution, too

Jefferson has spent a lot of time sampling spots such as those Walmart rain-retention ponds and the ditches near strip malls. Well-designed ones soak up water so that cities won’t flood. But she’d like this all-natural tech to clean the water, too. That’s why engineers have put a lot of thought into how they build these sites.

Not just holes in the ground or low spots near the side of a road, they are carefully designed to also work as water filters. For that, they need to soak up water and then let it slowly drain through. At many sites, that won’t happen without help.

Enter the urban rain gardeners. They top these sites with many of the same plants you’d see alongside a street or near a store. That’s not what makes them special, though. What’s underground is.

Below the plants is “a specific mixture of sand and organic material and finer particles,” she says. These allow water to soak through, “but not so fast that you can’t grow plants in it.” Beneath the soil is a layer of gravel. Underneath that is more normal soil. There might also be a pipe to drain away the water once it reaches the bottom.

As these rain gardens slow the flow, their gravel and sand help soak up pollutants. And once many pollutants get in, they don’t come out. They get “bound to the soil in such a way that they’re unavailable to water,” Jefferson reports. For instance, she found that there’s “a very low chance that those [traffic-related] metals are going to come out of the soil and pollute the stream later.”

Storm water also is a major source of microplastics, from the tiny bits produced as tires scrape along the road to bits of torn up plastic bags. Rain gardens help keep those plastic bits out of waterways, too. That’s the finding of a team of researchers from Canada and the United States. They described their findings May 5 in ACS ES&T Water.

Jefferson and her colleagues have shown that urban rain gardens built more than seven years ago can soak up pollutants today as well as they did when they were new. Over far longer time periods, however, those gardens will have to be cleaned or rebuilt to remove the buildup. Jefferson and her colleagues published their findings in the April 2020 Science of the Total Environment.