COVID-19 can infect kids — and risks sickening some severely

Concerns intensify as the super-contagious delta variant sweeps across the globe

As kids return to classrooms, concerns grow about how to keep them safe from the coronavirus, especially its new, super-infectious delta variant.

izusek/E+/Getty Images Plus

This fall, millions of U.S. children are heading back to school in person, many for the first time in more than a year. At the same time, the new delta variant has sent cases of the coronavirus surging. The collision of these two events worry many people, including health officials.

Most kids still have not been vaccinated against COVID-19. That makes them one of the groups most vulnerable to the virus. Now crowd these kids together and mix in a super-infectious variant. Suddenly, you’ve got the perfect recipe for spreading COVID-19 — at least if extra precautions aren’t taken (such as wearing masks).

Vaccines offer the best protection. Yet many children don’t yet qualify to get COVID-19 shots. While vaccines for children younger than 12 are in testing, it could still be months before they’re offered to most children through middle school. And their younger siblings will likely have to wait even longer.

Even once vaccines are in hand for the youngest, it’s not clear how many will get the shots. Right now, 12-year-olds and teens can get a COVID-19 vaccine. Still, most haven’t gotten the shot. Some people have even questioned whether kids need a vaccine. After all, their risk of becoming deathly ill from COVID-19 is far less than in adults.

All that is true. Most kids who get COVID-19 recover with no long-lasting effects. But a year and a half into the pandemic, there’s still much that researchers and doctors don’t know about what the disease can do to kids. For instance: How often do kids develop lingering symptoms, also known as “long COVID”? Why do some healthy children develop serious, run-amok inflammation weeks after recovering from COVID-19? In some kids, this complication appears in kids who didn’t even know they had been infected.

Now the delta variant is adding new questions. Studies largely in adults show that this variant makes people sicker — and more quickly — than earlier versions of the coronavirus. Will it hit kids harder too?

Right now, there are few data on the delta variant’s risk to kids. But the emerging picture suggests that while the virus poses little risk to many children, it can be quite serious for some.

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

The threat to kids

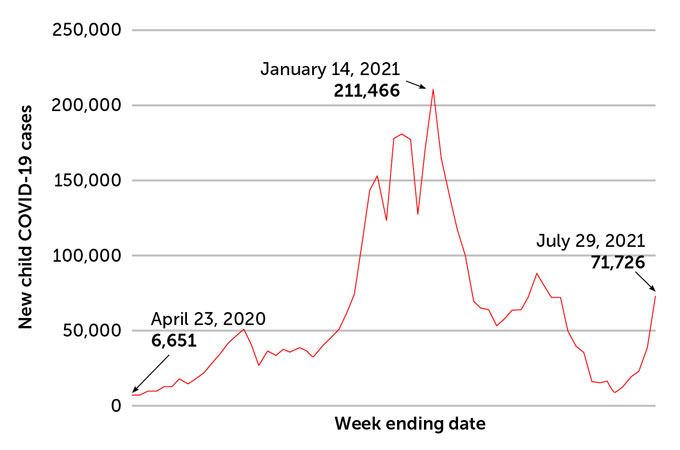

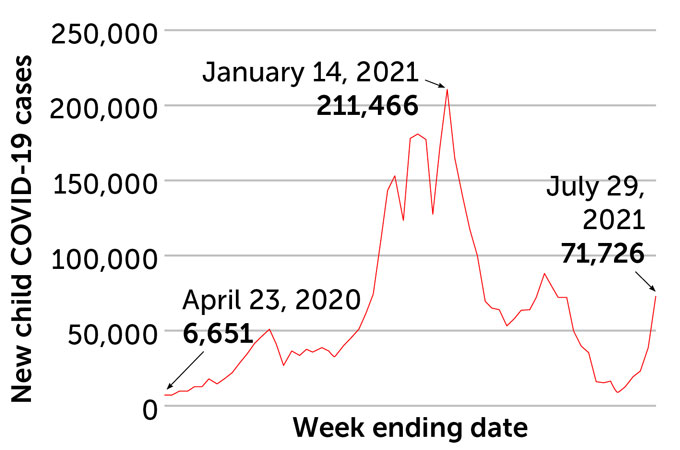

COVID-19 infections in kids have been growing. From August 6 to 12, there were 121,000 new COVID-19 cases in children. That number was reported by the American Academy of Pediatrics. It was a big jump from the 93,824, a week earlier — and 71,726 new cases in the last week of July. That was already nearly twice as many as a week before that (38,654 cases).

As infections rise, so will the number of hospitalizations and deaths. With millions of children infected, says Debbie-Ann Shirley, even a small share “adds up to tens of thousands of children being hospitalized for COVID-19.” Shirley works at University of Virginia Health. That’s in Charlottesville. There, she studies infectious diseases in kids.

Many infected kids get away with no symptoms, or with only a few sniffles. For others, the coronavirus infection can be life-changing, notes Andrew Pavia. He’s an infectious diseases doctor. He treats children at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. If you’re the child that ends up in a hospital’s intensive care unit, or ICU, for a week, “there’s nothing mild about that,” he says. Or what if some child “develops long COVID and flunks out of a semester of school, and doesn’t get to college? Or loses their athletic scholarship?” Those certainly are big deals.

“It drives me crazy to hear over and over again that the virus [that causes COVID-10] is not serious for children,” Pavia said. “By every measure,” he explains, COVID-19’s “impact is greater than the impact of influenza.” He shared that observation July 13. He was speaking at a news conference. It was sponsored by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC, began tracking flu deaths in 2004. Since then, U.S. childhood deaths from flu have ranged from a low of 37 in the 2011–2012 flu season to a high of 199 in the 2019–2020 season. Flu nearly disappeared in the 2020–2021 season. Precautions against the coronavirus helped limit the flu’s spread. It did the same for some other respiratory illnesses (except some colds, for reasons that are still a mystery).

Last year’s flu season set a new low. Just one childhood death was reported. But just since January 2020, COVID-19 has killed 423 of the nearly 4.3 million U.S. kids who became infected. In the week between August 4 and 11, seven kids died of COVID-19.

“Anything that kills more than 350 children a year is going to automatically rank in the top 10 causes” of childhood death, says Shirley. And COVID-19 has killed nearly that many.

Kids remain a small share of the 625,000 people who have died from COVID-19 in the United States. Still, their numbers have raised alarm bells for some health experts.

Imagine “if 300 children had died over the past year from lightning strikes or from shark attacks,” says Taison Bell. “We would be doing things a lot differently when it came to going to the beach or being outside when it was raining,” says this doctor. He focuses on critical care and infectious-disease medicine. He also directs UVA Health’s ICU.

What’s more, not all U.S. kids suffer equally from COVID-19. For instance, 18.5 percent of the U.S. population is Hispanic or Latino. Yet Hispanic and Latino kids account for 36 percent of child coronavirus deaths. Black children also are overrepresented among child deaths from COVID-19. While 13.4 percent of the U.S. population is Black, about 22 percent of COVID-19’s childhood deaths were Black children.

Serious consequences

Roberta DeBiasi has seen her share of children who are really sick with COVID-19. At Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C., she’s chief of infectious diseases. Nearly 2,900 children have been treated there for the coronavirus. Of those, more than 550 were hospitalized. Some 175 ended up in intensive care.

Nationwide, kids account for between 1.3 percent and 3.5 percent of people hospitalized for COVID-19. Like adults with serious cases of the new coronavirus, children who end up in the hospital tend to have underlying medical conditions. These range from obesity and lung diseases to illnesses affecting their nerves and muscles.

Another 165 kids have been treated at Children’s National Hospital for MIS-C. That’s short for multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. The immune system in its victims kicks up inflammation to such a degree that it can lead to organ failure. It appears about four to six weeks after an infection with the coronavirus. It can affect even kids who initially had mild cases or no symptoms at all.

There’s no good way to know who will develop MIS-C, DeBiasi says. It can happen even to formerly healthy children. “That’s what makes it a little bit scary,” she says.

Children of color tend to suffer more severe consequences of MIS-C. Black and Latino children were overrepresented among kids treated at Children’s National for the illness. DeBiasi and colleagues shared that finding June 25 in the Journal of Pediatrics. Nationally, 63 percent of the 4,404 children with confirmed cases of the rare syndrome have been Black or Latino.

Some medications that calm the immune system help. And many children seem to recover fully. But as of this past July 30, MIS-C has claimed the lives of 37 U.S. children. Doctors have known about the rare inflammatory condition for only a little more than a year. And the long-term impacts of MIS-C on a child’s health are yet one more mystery. DeBiasi and her colleagues have launched a study of its long-term effects.

Some kids suffer ‘long COVID’

They also are looking at long COVID in kids. It can encompass a mix of symptoms. They can range from exhaustion, shortness of breath after activity and loss of taste and smell to problems with thinking and memory. And the effects can last weeks or months. “If you’re in school and trying to learn,” DeBiasi notes, “it’s not good to have memory disturbances.” Even seemingly mild cases “do have an impact on your quality of life.”

No one is quite sure how common long COVID is in kids. DeBiasi’s new three-year study will track more than 1,000 children and young adults who have had COVID-19. Their impacts will be compared to other kids in the participants’ households who never got COVID-19.

In one study of children in the United Kingdom, COVID-19 usually ran its course in about five to seven days. Younger kids tended to get better faster. But about 4 percent of the children still had symptoms a month after falling ill. That’s according to an August 3 report in Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. And these long-term effects showed up more often in 12- to 17-years-old than in younger kids. Almost 2 in every 100 children still had symptoms two months into the illness, the researchers found.

In a Swiss study of 109 school children, about 4 in every 100 had at least one symptom three months after getting COVID-19. Researchers shared those findings July 15 in JAMA.

In both studies, kids who had colds or other respiratory illnesses sometimes had symptoms also lasting a month or more. This suggests the virus causing COVID-19 isn’t the only one that can cause lingering impacts.

Kid cases

Overall, children have accounted for about 14 in every 100 COVID-19 cases since the start of the pandemic. With the delta variant making inroads among unvaccinated people, cases in children again are on the rise. These data are from 49 states (Nebraska stopped reporting cases at the end of June), New York City, Washington, D.C., Puerto Rico and Guam.

COVID-19 cases reported in children in the United States, April 2020–August 2021

Has the delta variant changed things in kids?

Over the entire course of the pandemic, children have accounted for 14.3 percent of all infections. That’s a finding of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Since the delta variant’s emergence, kids now make up a slightly larger share of cases. They were 19 percent of all U.S. cases in the last week of July. That was up from just under 17 percent the week before. By mid-August, they were 15 percent.

But that higher share of kids than early in the pandemic may be because children under 12 can’t yet get the vaccine. Only about 30 percent of 12- to 17-year-olds are fully vaccinated. It may not mean kids are more susceptible to the virus. They may just make up a larger share of the group that remains vulnerable.

And although delta is more infectious, it is not clear whether it causes more severe illness in kids the way it appears to in adults. Some doctors are reporting that kids infected with the delta variant are getting sicker. But at Children’s National hospital, “We’re not seeing any difference in how sick the kids get,” DeBiasi says. There’s also no sign that they are more likely to end up in the hospital if they are infected with the delta variant, she says.

But there’s still basic math to consider: The more kids who get sick from this super-contagious variant, the more who could face severe or long-term illness.