Cloning boosts endangered black-footed ferrets

A species that nearly went extinct gains genetic diversity

Black-footed ferrets were once thought extinct. Captive breeding has brought back their numbers. Now cloning could boost their genetic diversity.

kahj19/iStock/Getty Images Plus

On December 10, 2020, a new baby black-footed ferret came into the world. Her species is one of the most endangered in North America. Named Elizabeth Ann, she quickly grew up into a chattering, tumbling, nipping ball of energy. This little girl doesn’t know it, but she could be key to saving her species.

Kimberly Fraser is an education specialist at the National Black-footed Ferret Conservation Center in Wellington, Colo. And she knows Elizabeth Ann well. “She loves getting in tubes and boxes and paper bags. I would say she’s very happy,” Fraser says.

What makes this little ferret special is that she is a clone. She’s a genetic copy of an animal that died decades ago.

More than five million black-footed ferrets once lived on the great plains of North America. They were cunning hunters that preyed almost entirely on prairie dogs. When European settlers moved to the area and built farms, they destroyed these animals’ habitats. They also poisoned and killed prairie dogs, leaving many black-footed ferrets without food. A plague also spread through the populations of both species. In 1979, experts declared the black-footed ferret extinct.

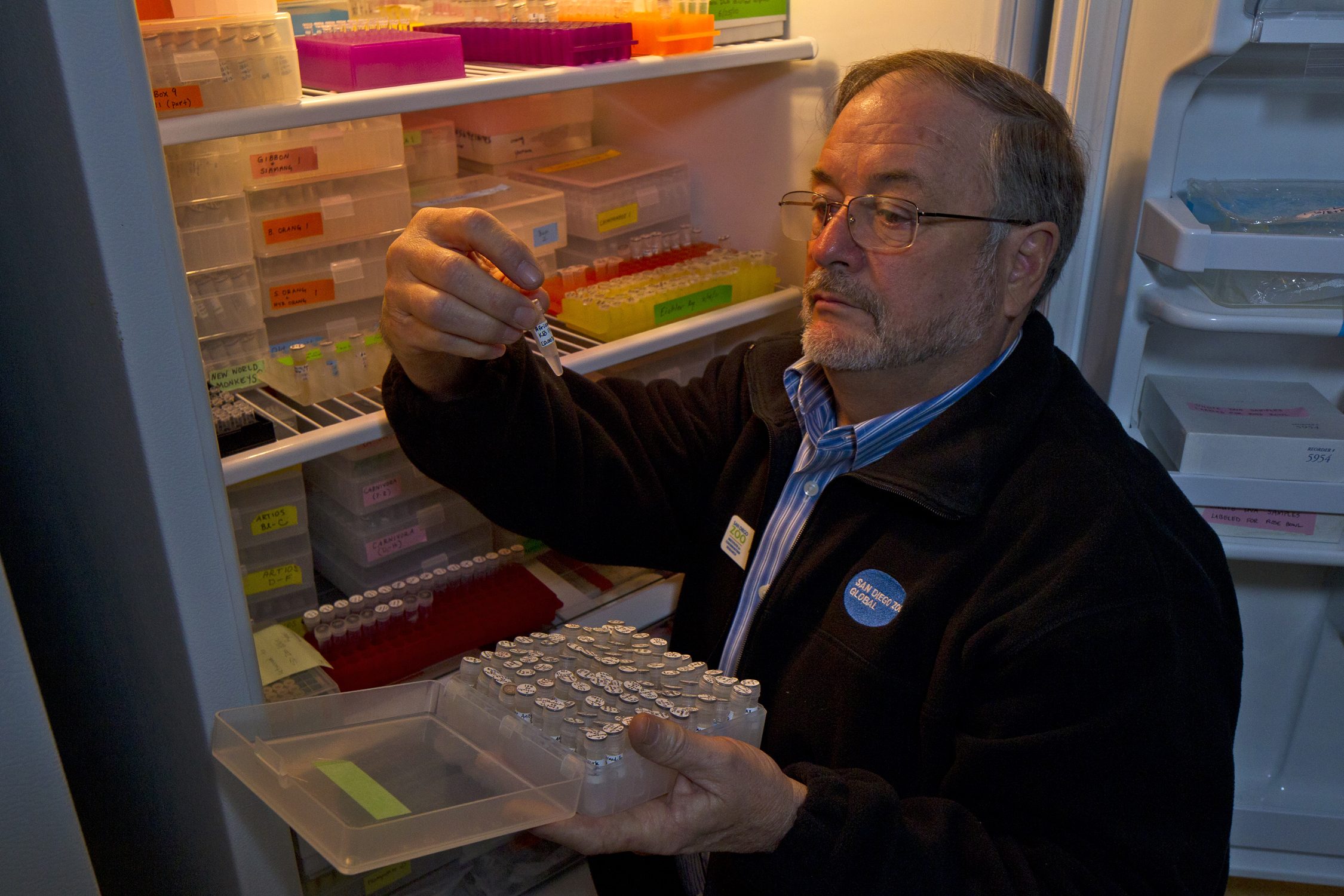

But then, in 1981, there was “an electrifying announcement,” recalls Oliver Ryder. A farmer in Wyoming had discovered a small community of wild black-footed ferrets! Ryder, now a genetics expert at San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance in California, was elated. Conservationists captured the wild ferrets and began a captive-breeding program. They hoped to save the species.

Ryder had the foresight to ask for cell samples from several of the animals that were captured. “It will be useful for reasons we don’t know,” he recalls saying. For each animal, he received a little glass vial containing a tiny piece of skin. The cells from this skin were preserved in a way that makes it possible to revive and grow them.

Back then, he couldn’t have imagined how very useful these preserved cells would turn out to be.

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

Rebuilding a population

The captive-breeding program was challenging. The plague still threatened prairie dogs and ferrets. Over time, though, scientists have been able to reintroduce wild ferrets to parts of Wyoming, Montana, South Dakota, Arizona, Mexico and elsewhere. Scientists also developed a vaccine for the plague. The wild population now numbers around 350, with around 300 more still living in captivity.

However, only seven of that original captured ferret population had pups that survived to have babies of their own. That meant every black-footed ferret in the world was closely related. They all had very similar genes. With each generation, offspring were more likely to have genetic problems. They needed genetic diversity to survive, says Samantha Wisely. She is a genetics expert who studies conservation at the University of Florida in Gainesville.

Enter Elizabeth Ann. She is a clone of Willa, one of the ferrets whose cells Ryder preserved back in 1986. Until 2020, Willa had no living descendants. So her genes were quite different from the rest of the species. Elizabeth Ann’s birth was “a leap of hope” for the species, says Fraser. Wisely was also excited. “I was over the moon,” she says.

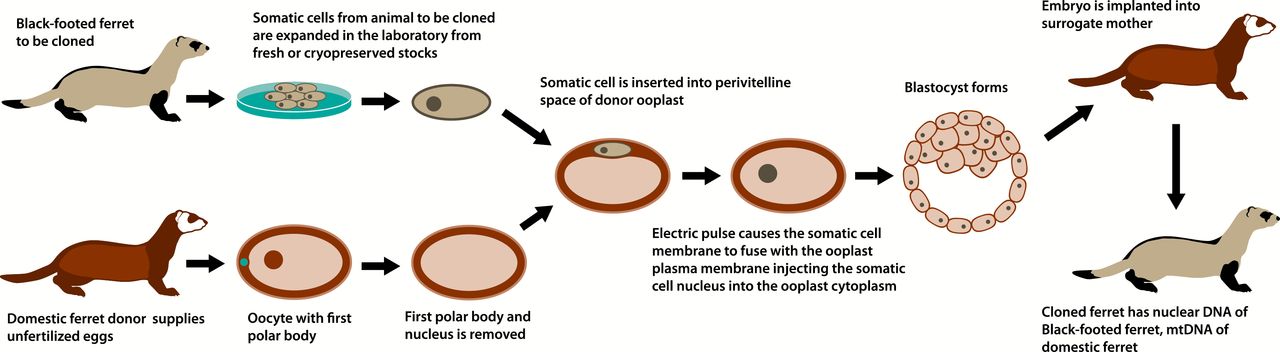

In the cloning process, scientists removed the entire nucleus, or middle, from Willa’s cells. This nucleus contains genes that are akin to a recipe for creating an animal identical to Willa. Researchers also took egg cells from a domestic ferret and removed their nuclei. Then they transferred Willa’s nuclei into these egg cells. The egg cells began to divide, becoming embryos. The researchers then put the embryos into another domestic ferret. This ferret carried the babies until they were born.

The only embryo to survive the entire process was Elizabeth Ann. Her birth showed that it is possible for DNA from a creature that died many years earlier to live again — and potentially boost an entire species.

Meanwhile, Ryder continues to collect cells from as many animal species as possible. He thinks this work is important because, “We love the world we live in and we want to protect it.”

The collection he works on is called the Frozen Zoo. It has samples from more than 1,100 different animal species so far. Almost all are mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians. But at least 13,000 of these types of animals are threatened or endangered with extinction. He hopes that researchers will donate cells from as many of these species as possible. And then maybe someday, someone will use those cells to save another species.