A spider’s feet hold a hairy, sticky secret

Powerful microscopes reveal dazzling hair structures that give then a gift of grip

Meet the tiger wandering spider, a favorite among scientists who study arachnids. In a new study, researchers studied this kind of spider to better understand how tiny hairs at the end of their legs help these creatures stick anywhere.

Sergio Amiti/Getty Images

Many animals climb, but few do it as well as the spider. These eight-legged critters scale walls and skitter on ceilings, clinging in seemingly impossible ways. Now researchers have turned up surprising clues as to how spiders can stick to almost any surface. The structure of tiny hairs at the tip of the spider’s legs likely help the creature hang on.

Clemens Schaber is a zoologist — a scientist who studies animals — at the University of Kiel in Germany. He led the new study, which was published June 11 in Frontiers in Mechanical Engineering. The finding was part of his research on how spiders move. Adhesion, or stickiness, “is an important part of that,” he says.

Spiders don’t have a sticky liquid on their feet. Instead, they use “dry” adhesion. Animals that use dry adhesion can stick and unstick to surfaces easily. Scientists have long studied the hairs on a spider’s foot to understand how they do it.

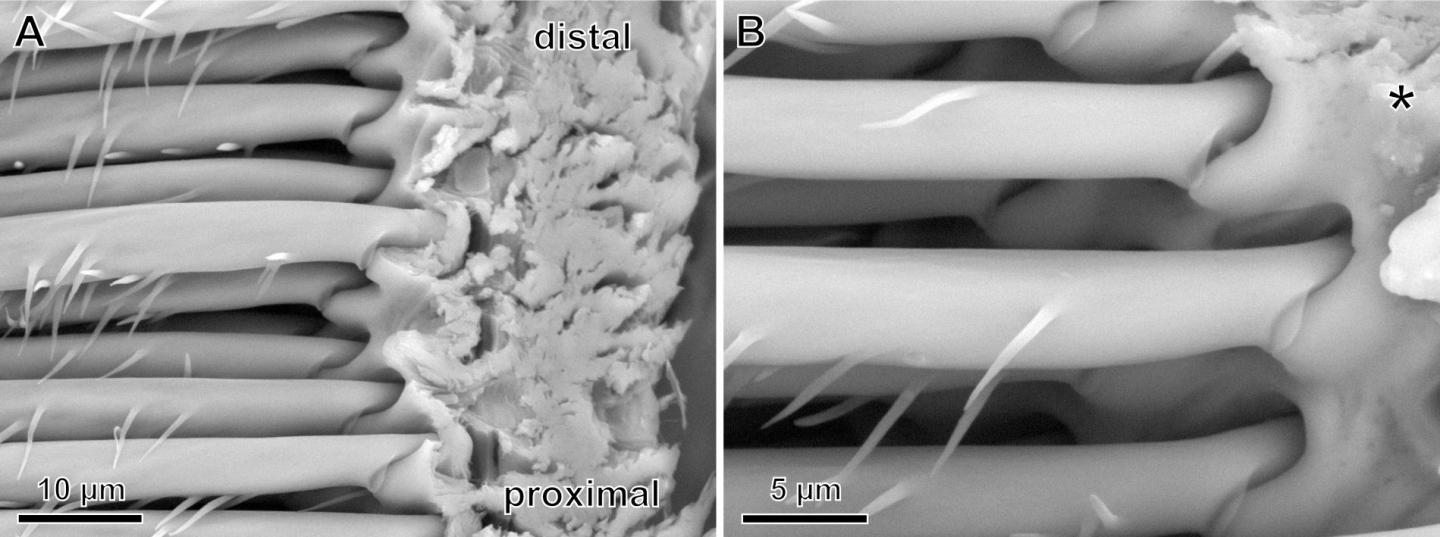

At the end of a spider’s leg, coarse fibers splinter into smaller hairs. At the tips of these hairs are small, flat structures that look like spatulas. They’re even called spatulae. When the hairs touch something, they form bonds with atoms at the surface and stick.

Before this latest research, Schaber knew the hairs were important for adhesion. He wanted to know more about why they worked so well. He and his colleagues chose to study this in Cupiennius salei spiders. Often called tiger wandering spiders, they live in South and Central America.

The scientists first tried to pull tufts of hair off the spider legs using tweezers. But the entire leg often came off instead. This is a natural defense that the spiders use to escape predators. The researchers then used a powerful microscope to view the hairs up-close. Schaber expected that all the hairs would point in the same direction, more or less.

“But it wasn’t like that,” he says. Instead, when as the researchers looked at the tip up close, they saw hairs pointing all over the place. “The ends of the hairs were all a little bit different in direction,” Schaber says.

Sticky stuff

The researchers then tested the stickiness of the hairs on different materials, including glass. They found that some hairs had the strongest adhesion at one angle. Others worked best at other angles. Concludes Schaber, this mix of angles and adhesions may help the spider stick no matter how it touches a wall.

Having lots of sticky hairs pointing in different directions probably gives the spider its ability to go anywhere, says Sarah Stellwagen. She’s a biologist who studies spider stickiness at the University of North Carolina in Charlotte. “If you have one point of contact, it’s probably not going to work very well,” she says. “But if you have lots of points of contact, that’s how dry adhesion works.”

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

The study “is quite interesting,” says Ali Dhinojwala, a materials scientist at the University of Akron in Ohio. “It shows us new ways to think about making structures stick to surfaces.” These structures might even inspire new types of tape. “They teach us a lot about how nature has evolved common strategies.”

Schaber says his lab tested another application. The scientists covered a glove in tiny spider hairs, in different directions. That glove could support the weight of a person. Sticking anywhere. With such a glove, anyone could develop the superpowers of a spider.