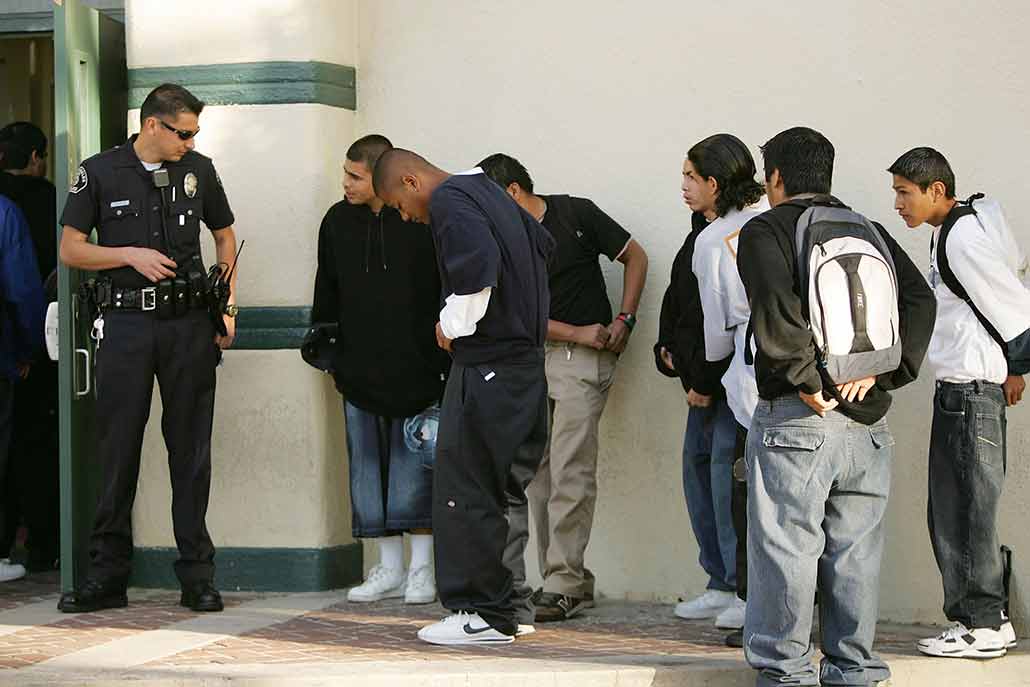

Discriminatory policing takes a toll on teens and tweens

Research points to higher risks for Black boys and girls than for white kids the same age

Teens and tweens of color face higher risks of getting hurt in encounters with police than do white youths their age.

Михаил Руденко/ iStock/ Getty Images Plus

“You’re acting like a child,” the police officer said.

“I am a child,” the 9-year-old Black girl replied. She kept crying for her dad.

This past January, a report of “family trouble” had brought police to the girl’s home in Rochester, N.Y. Officers told her to get into a police car. Instead, she sank into the snow. As she screamed on the ground, an officer clamped handcuffs on her wrists. Police pushed the crying girl partly into the car. But she wouldn’t lift her legs inside. Another officer then squirted her in the face with pepper spray.

In February 2021, police arrested a 13-year-old Black boy in Baton Rouge, La. The officer restrained the teen by locking his arm around the child’s neck. He relaxed the hold only after a bystander called out, “You’re choking him!” And in March 2021, police killed a 13-year-old Latino boy in Chicago, Ill. The boy was raising his hands when he was shot.

New studies show that compared to their white peers, children and teens of color are more likely to be harmed by police. Research has also linked such differences in policing of young people to higher risks of mental-health problems later on.

From 2003 to 2018 in the United States, 140 12- to 17-year-olds died in police encounters. All but nine of those children had been shot by the police. During the same period, police killed about 6,500 adults in the United States. Compared to their numbers in the population, Hispanic teens were nearly three times more likely to be shot and killed by police than were white teens. Among Black teens, the risk of being shot and killed by police was about six times that of white teens. Researchers shared those findings in the December 2020 Pediatrics.

Hospital data also point to kids’ unequal risk of being wounded by police. Kriszta Farkas is an epidemiologist at the University of California, Berkeley. She studies factors leading to inequalities in health. Recently, she and others analyzed hospital data for California from January 2005 to December 2017. They found 15,967 cases where youths up to age 19 had been harmed during contact with law enforcement.

“Boys are more likely to be physically hurt by police than girls” — about seven times more likely, Farkas says. The highest rate of injuries was among 15- to 19-year-olds. In that group, Black boys were roughly 3.5 times more likely to be harmed than white boys.

Police were less likely to injure younger teens and tweens than older youth. However, racial disparities were greater in the younger 10- to 14-year-old group. Here, the risk of harm from police was 5.3 times higher for Black boys than white boys,

Although boys were more likely to be harmed, Farkas found that there were larger racial inequities among girls, especially younger ones. Indeed, the new study shows that “Black girls are uniquely harmed by policing,” Farkas says. For instance, Black girls aged 15 to 19 were more than 4.3 times as likely to be hurt by police as were white girls of the same age. And among kids aged 10 to 14, Black girls were 6.7 times as likely to be hurt by police as white girls. Overall, white girls reported far fewer injuries from law enforcement than any other group.

Her team shared its findings September 7 in JAMA Pediatrics.

Some feel dehumanized

Results from that study are “not surprising to those who have these lived experiences,” says Dominique Johnson. Based in New York City, she worked on community engagement with the Center for Policing Equity. Today she works with AMC Networks. As a child she found that others judged Black people like her differently. White children did not have that burden, she said.

Black teens can feel especially vulnerable when they are dehumanized because of their race, Johnson says. That happens when they are treated as if they don’t deserve dignity or respect.

Monique Jindal is a pediatrician at the University of Illinois at Chicago. She and others reviewed 29 studies on police contact with Black youth. Some studies found links between experiences with police and mental-health problems. Many young people said they felt unsafe, stressed out, angry, sad or depressed. In several studies, Black youths said they felt hopeless, fearful or unable to just be kids. The team shared its report, too, in the September 7 JAMA Pediatrics.

“It’s a very harsh reality for children of color,” Jindal says. From a young age, Black children come into contact with police in parks, schools, neighborhoods and elsewhere. Yet “kids are going through critical development periods during this time,” she explains. Healthy development calls for children to feel safe. They need to feel they belong.

Unfortunately, Jindal says, Black children often learn, “there’s this social institution that is not there to protect them — that may actually do them harm.” That can affect a child’s view of society and the world. It can also mess with their ability to just be a kid. They may worry that police will see them as being up to no good, for example, instead of just hanging out with friends. Or they may avoid places, such as a park, because they don’t want to be hassled by police.

Seen differently

Phillip Atiba Goff is a social psychologist at Yale University in New Haven, Conn. He also heads up the Center for Policing Equity. Goff spoke at a May 21 webinar about policing and racism. The Association for Psychological Science hosted the event.

In general, police are less likely to use force against children, compared to adults of the same race, Goff says. But data from nine cities show that is less true for Black children than for white children. In addition, police were more likely to use force against Black children than against white adults.

“In these nine cities, whiteness is more protective than childhood,” Goff says.

In an earlier study, a group of mostly white participants saw Black children over age 10 as less innocent than non-Black children in the same age group. And police were more likely to estimate higher ages for Black and Latino children, compared to white children.

“In the research world, we call this being ‘adultified,’” says Farkas, who did not work on that study. “But another way of thinking about it is not being allowed by the world around you to live your life as the carefree child or young person that you should be.”

Farkas says her group’s work adds to “scientific evidence on policing as a form of structural racism.” That term, she adds, refers to “the patterns and practices that a society uses to give rise to and support racial discrimination.” In this case, she says, “policing unjustly, or unfairly, shapes the lives of Black children and teenagers in negative ways, compared to white youth.”

“People in different racial groups are no more or less likely to break laws,” explains epidemiologist Catherine Duarte. Yet people in racial minority groups “are more likely to experience police contact.” And that can lead to more risk of harm. Duarte worked on the study with Farkas at UC Berkeley. She teaches at Stanford University in California.

In a separate study, Duarte and others looked at how public policy shapes young people’s contacts with police. Some policies affect whether there’s a police presence at schools. Other policies deal with policing in different neighborhoods. Still other policies shape police contacts with young people who don’t have stable housing. Various laws have also increased funding for police but not social services. Other laws expanded the crimes young people may be charged with.

Also, many laws that don’t seem to discriminate end up being applied more harshly against children of color than against white children, Duarte says. For example, police are more likely to stop children of color than white children. And such police stops are often less intrusive when they involve white children. The group shared its findings in the American Journal of Public Health in September 2020.

“In public health research, we find that all of this is linked to worse health,” Duarte says. That’s especially true for people in minority groups who experience racism. Unjust differences in health are a sign of basic problems in our social systems, and we all have a responsibility to address them, she says. “Everyone,” she notes, “should have the opportunity to live healthful lives.”

Taking action

Science is critical to knowledge and advocacy on issues such as racism, Johnson says. Still, she adds, “I wish these disparities did not exist and that we did not have to utilize statistics and data to prove our humanity.”

Adds Jindal, “Hopefully people are waking up, and they are starting to really look at the ways that we have not protected children.” She encourages youths who are not in a minority group to ask trusted adults what can be done to change things. And she hopes young people will have empathy for friends and classmates with different racial identities.

Teens and tweens of color also should share their experiences with the adults in their lives who love and care about them, Jindal says. If they have negative experiences with police or others, “they should find someone they trust to talk about it.” That could be a parent, teacher, doctor or someone else.

Farkas likewise urges young people to talk about their feelings with friends, family members and other trusted adults. It’s important to take care of yourself and people you care about, she says. And, if you have the energy and opportunity, “learn about and engage with this topic, even if in small ways.”