Retractions: Righting the wrongs of science

False findings must be acknowledged and 'corrected' to keep science credible

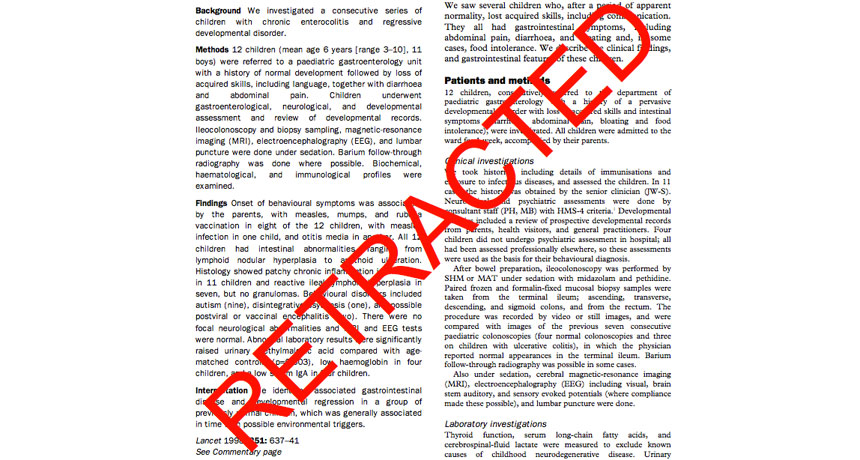

When a journal retracts a published study, the research doesn’t vanish. Instead, it gets flagged as unreliable. For the Wakefield study, part of which is shown here, the journal stamped a warning on each page that the paper had been retracted.

The Lancet

If the results from an experiment look too good to be true, look again.

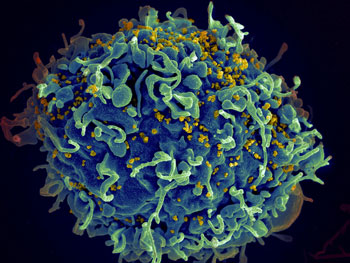

Those are wise words to remember. Consider, for example, a recent case of what looked like a breakthrough in treating the deadly virus HIV. The findings turned out to be bogus. All it took was a second look.

A study reporting success with the vaccine was published — then later retracted. When a journal retracts a paper, the study is removed from the body of scientific evidence. It means the study is so flawed that it never should have been published in the first place.

Retractions can pack a nasty sting for the scientists whose work was affected. But those retractions also play a necessary role. Acknowledging mistakes helps science move forward.

In the case of the virus “breakthrough,” biologists from Iowa State University, in Ames, reported their exciting results in the journal Retrovirology. They had developed a vaccine for HIV, or human immunodeficiency virus. This germ causes acquired immune deficiency syndrome, or AIDS. It kills more than a million people each year. So a vaccine might save many lives.

But excitement over their new findings didn’t last.

A year after the 2012 paper was published, government scientists looked into the research. And those outside investigators discovered that one of paper’s authors had committed a crime. He had tinkered with the experiment. In the lab, this biologist had added human antibodies to the rabbit blood. The added antibodies made the vaccine appear to be working, when in fact it wasn’t. Bottom line: The published results were bogus.

But there was a bigger issue here than just cheating. The experiment also had wasted a lot of time and government money. The researcher who had tampered with the blood left his university in October 2013. By early 2014, Retrovirology had retracted his team’s paper.

Retractions may follow a study by months or years. In August 2014, for example, researchers reported on how grizzly bears can put on fat for the winter without developing diabetes, a disease connected to obesity. Thirteen months later, that study was retracted. An investigation revealed that one of the scientists had manipulated his team’s data. And that meant the paper’s conclusions could not be trusted.

Self-corrections

Retractions are more than just simple corrections. A correction might fix a small error. Maybe a number has to change, or a graph has to be revised. Perhaps a conclusion must be stricken from the text. But most of the affected study holds up. In contrast, a retraction takes back the whole study. The study doesn’t disappear. But all of its findings are forever branded as unreliable.

That’s why a true retraction casts a long shadow. It embarrasses scientists, institutions and journals. A retraction also can be expensive. Iowa State reportedly had to return nearly $500,000 to the U.S. government. That money had helped fund the HIV vaccine research.

Fanelli is a scientist who works at the METa-Research Innovation Center at Stanford University in Palo Alto, Calif. There, he analyzes trends in retractions and the scientific process. Fanelli says retractions make science different from any other field of knowledge. They “allow the truth to emerge,” he explains. Science is collaborative, meaning it advances as the work of one person or group adds to or reinterprets earlier findings. In this way, new knowledge emerges. But for that process to work, the published results of past studies need to be accurate. Scientists have to trust what — and who — came before.

“Science is messy, and sometimes things go wrong,” says Joshua Krieger. He’s a doctoral student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge where he studies the effects of retractions. “And it’s best to be really transparent about what went wrong.” By transparent, he means clear about what is unreliable — and why.

Rare and rising

In 2014, a scientific journal in India published a paper that addressed plagiarism. To plagiarize is to copy someone else’s work. But in April 2015, that paper was retracted — because it had plagiarized an earlier paper.

Other retractions involve research that seems almost unbelievable. In May 2005, for instance, biologists reported on a new and successful way to clone — make exact copies of — human embryos. Human cloning is a hot topic. The study received a lot of press. Twice. The first time was when the study initially appeared. The second time was later that year, after an investigation showed that those findings had been fraudulent. So that paper, too, was retracted.

This past May, Science retracted a paper it had published just five months earlier. That earlier paper had claimed to have data showing that a short conversation with a gay person could change a person’s attitude toward same-sex marriage. The finding received a lot of news coverage. According to the top editor at Science, one of the study’s two authors was not honest about who paid for the research or how it had been run. Nor had that scientist publicly shared his original data. Those data might allow other experts to confirm — or deny — the study’s conclusions.

It’s important to keep in mind that in the world of science, retractions remain rare. According to a 2011 Nature study, roughly 400 papers were retracted in 2010. Compare that to the roughly 1.4 million papers that journals publish each year. However, 400 still is about 10 times the number of papers retracted in 2001. That means retractions have been climbing at a brisk pace.

The trend suggests scientific dishonesty is on the rise. But that’s the wrong way to look at the numbers, says Fanelli. He sees the increasing number of retractions as a good thing. It shows scientists are paying more attention to accuracy.

“Serious flaws or fraud can taint the literature,” he says, “and those are results you don’t want.”

Damage in fraud’s wake

Bad science can have serious consequences. In 1998, The Lancet published a small study led by a surgeon named Andrew Wakefield. It sent parents around the world into a panic. The study focused on a group of 11 boys and one girl. Wakefield and other scientists reported finding a link in these kids between a common childhood vaccine and autism. That’s a disorder that affects how the brain develops. Parents who learned of the study worried that their kids might become autistic after getting a shot to protect against measles, mumps and rubella.

In January 2010, a government panel in the United Kingdom announced that it had found many problems in the original study. Wakefield, for example, had received money from lawyers involved in lawsuits against vaccine manufacturers. In February of that year, The Lancet retracted the paper.

Still, the damage was done. Many parents refused to vaccinate their children — and still do — for fear of autism.

Until the last decade or so, says Fanelli, retractions didn’t receive much publicity. Scientists often were not aware of a retraction. Journals assumed “that somehow they would know to avoid retracted papers.” However, retractions seldom received as much attention as the original headline-grabbing studies.

That’s now changing. Most importantly, journals have becoming more attentive to signs of potential fraud.

The wrong mice, and other wrongs

Not all retractions are created equal. Honest mistakes lead to some. Other retractions reflect intentional fraud. In 2009, Fanelli studied previous surveys of scientists. He found that nearly 2 percent of them admitted to falsifying, fabricating or modifying data at least once.

The problem: Even a little fakery is a major no-no.

Mistakes also happen. And when they are not too big, the authors of a study might publish a correction. That’s what a New York City team did recently. They had mapped the genetic debris left by organisms big and small in the local subway system. The scientists initially turned up genes they attributed to the bacteria causing anthrax and bubonic plague. And they reported that claim as part of a paper describing their findings in the March 3 issue of Cell Systems.

When other scientists became skeptical of the plague and anthrax findings, the original scientists performed follow-up tests and analyses. And these failed to confirm their original claim. So on July 29, the scientists published a formal correction to their original paper. The paper was not retracted, just changed to reflect a mistake.

Still, some mistakes are too big to solve with a simple correction. Consider a 2006 paper on gene mutations in mice. Its authors were scientists at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md. That’s a medical school run by the federal government. A few years after publishing their data, the same researchers repeated their experiments. This time, they came up with very different results.

In probing why, they soon discovered one team member originally bought the wrong type of special laboratory mice. In 2010, the researchers contacted the journal and explained the mistake. It retracted their paper.

Clifford Snapper, the lead researcher, later admitted in an email to Ivan Oransky that “The retraction was a painful experience, but absolutely necessary.”

Oransky is a physician, medical school professor and science journalist in New York City. In 2010, he and science writer Adam Marcus launched Retraction Watch. As its name suggests, the website reports on retractions. Since launching the site, the two have publicized retractions of all types.

Until a few years ago, Oransky says, people thought most retractions arose from honest error — such as with the mouse study. They thought wrong.

In 2012, a team of biologists looked at more than 2,000 retracted studies in biology and the life sciences. (The oldest had been published in 1973 and retracted in 1977.) Nearly 7 out of every 10 studies had been retracted because of misconduct, the researchers reported. Infractions included fraud, plagiarism or a scientist having published the same study more than once. This analysis of retractions appeared three years ago in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Science builds on the work of past researchers. So, when a scientific paper is published, its authors list other studies that they had reviewed while doing their research. These are called citations. A paper may turn out to have big problems if it cites research that was believed to be true but later turns out to be false or wrong in some way. Scientists have to avoid citing retracted studies because no one wants to have based new work on invented or incorrect data.

Handling the fallout

Journals handle retractions in different ways. Some don’t publicize what problems prompted them to retract a study. That makes it difficult for scientists who had read the original study to tell the difference between fraud and honest mistakes. Yet that’s an important distinction to make, notes Krieger at MIT.

“Science can move forward when we understand what went wrong,” he says.

A few years ago, Krieger was part of a team of economists who wanted to know how retractions changed a scientific field. The team studied more than 1,100 retractions. They released their findings in 2013 in a paper published by the National Bureau of Economics. When a paper is retracted because of fraud or misconduct, scientists often mistrust other papers in the same field, the economists learned. But when the reasons for a retraction are due to honest error, other papers aren’t doubted as much. Some fields — and scientists — have been cited more after retractions due to honest errors.

“We found that it’s important not just to announce that the work is retracted, but to announce why,” Krieger says. “Everyone who does research knows mistakes happen. But what matters is how well you document those mistakes. Don’t be a cheat and don’t make up data.”

Oransky agrees. “If you retract a paper for fraud, and it sounds like you were dragged kicking and screaming to the retraction, you will suffer and your field will suffer,” he says. “If you found the error yourself and retracted it for honest reasons, you could see a bump in citations [to it].” So researchers should be more honest, he concludes — not only because it’s the right thing to do, but also because it could help their careers.

Power Words

(for more about Power Words, click here)

anthrax A bacterial infection of sheep and cattle that can also be transmitted to humans.

antibody Any of a large number of proteins that the body produces as part of its immune response. Antibodies neutralize, tag or destroy viruses, bacteria and other foreign substances in the blood.

autism (also known as autism spectrum disorders) A set of developmental disorders that interfere with how certain parts of the brain develop. Affected regions of the brain control how people behave, interact and communicate with others and the world around them. Autism disorders can range from very mild to very severe. And even a fairly mild form can limit an individual’s ability to interact socially or communicate effectively.

biology The study of living things. The scientists who study them are known as biologists.

bubonic plague A disease caused by the bacteriumYersinia pestis. It’s transmitted by the bite of a flea that had previously bitten some rodent infected with the germ. This form of plague causes fever, vomiting and diarrhea. It also inflames the lymph nodes, causing them to swell. Those swollen tissues, called buboes, give this form of the disease its name. Known as the Black Death, bubonic plague killed millions of people in Europe during a series of outbreaks during the Middle Ages.

citation A short list of abbreviated details that can help someone find a published or unpublished piece of work, such as a scientific paper, article or video.

clone An organism that has exactly the same genes as another, like identical twins. Often a clone, particularly among plants, has been created using the cell of an existing organism. Clone is also the term for making those offspring that are genetically identical to some “parent” organism.

data Facts and statistics collected together for analysis but not necessarily organized in a way that give them meaning. For digital information (the type stored by computers), those data typically are numbers stored in a binary code, portrayed as strings of zeros and ones.

doctoral Having to do with a doctorate, a type of advanced degree also known as a PhD.

economics The social science that deals with the production, distribution and consumption of goods and services and with the theory and management of economies or economic systems. A person who studies economics is an economist.

embryo The early stages of a developing vertebrate, or animal with a backbone, consisting only one or a or a few cells. As an adjective, the term would be embryonic — and could be used to refer to the early stages or life of a system or technology.

fraud To cheat; or the resulting effects of something done by cheating. Or to make a mistake and intentionally cover up the error.

genetic Having to do with chromosomes, DNA and the genes contained within DNA. The field of science dealing with these biological instructions is known as genetics. People who work in this field are geneticists.

HIV (short for Human Immunodeficiency Virus) A potentially deadly virus that attacks cells in the body’s immune system and causes acquired immune deficiency syndrome, or AIDS.

immune system The collection of cells and their responses that help the body fight off infections and deal with foreign substances that may provoke allergies.

immunology The field of biomedicine that deals with the immune system.

journal (in science) A publication in which scientists share their research findings with the public. Some journals publish papers from all fields of science, technology, engineering and math, while others are specific to a single subject. The best journals are peer-reviewed: They send out all submitted articles to outside experts to be read and critiqued. The goal, here, is to prevent the publication of mistakes, fraud or sloppy work.

literature The books, studies and other writings published on a particular subject. Scientific literature usually refers to published papers or meeting abstracts describing new research findings or the reviews of multiple papers on a topic within some field.

measles A highly contagious disease, typically striking children. Symptoms include a characteristic rash across the body, headaches, runny nose, and coughing. Some people also develop pinkeye, a swelling of the brain (which can cause brain damage) and pneumonia. Both of the latter two complications can lead to death. Fortunately, since the middle 1960s there has been a vaccine to dramatically cut the risk of infection.

mumps A highly contagious childhood viral disease characterized visually by swollen cheeks and a puffy jaw due a swelling of the salivary glands. It causes flu-like symptoms, including fever, muscle aches, headaches and being very tired. It’s spread as influenza is, by sneezing, coughing or touching something contaminated with the virus, such as a patient’s hands, drinking glass or spoon. In rare cases, the disease can inflame the brain, spinal cord or other tissues or cause deafness.

mutation Some change that occurs to a gene in an organism’s DNA. Some mutations occur naturally. Others can be triggered by outside factors, such as pollution, radiation, medicines or something in the diet. A gene with this change is referred to as a mutant.

replicate (in biology) To copy something. When viruses make new copies of themselves — essentially reproducing — this process is called replication. (in experimentation) To copy an earlier test or experiment — often an earlier test performed by someone else — and get the same general result. Replication depends upon repeating every step of a test, one by one. If a repeated experiment generates the same result as in earlier trials, scientists view this as verifying that the initial result is reliable. If results differ, the initial findings may fall into doubt. Generally, a scientific finding is not fully accepted as being real or true without replication.

retraction (v. retracted) In science, this is aformal announcement that researchers (or the organization that may have published their findings) no longer stands behind published data. The initial report of those data will not disappear. It will just be flagged with a warning that the authors or publisher no longer trusts the data or findings as reliable.

rubella A formerly common childhood infection sometimes called the “German” measles or three-day measles. The short-lived infection tends to cause a slight fever and rash that spreads from the face to the rest of the body. Almost half of infected people show no symptoms. The big risk is to the baby of women who get the disease during pregnancy. The child may develop deafness, vision problems, heart defects, mental retardation and liver or spleen damage.

vaccine A biological mixture that resembles a disease-causing agent. It is given to help the body create immunity to a particular disease. The injections used to administer most vaccines are known as vaccinations.

virus Tiny infectious particles consisting of RNA or DNA surrounded by protein. Viruses can reproduce only by injecting their genetic material into the cells of living creatures. Although scientists frequently refer to viruses as live or dead, in fact no virus is truly alive. It doesn’t eat like animals do, or make its own food the way plants do. It must hijack the cellular machinery of a living cell in order to survive.

Word Find (click here to enlarge for printing)