World’s biggest colony of nesting fish lives beneath Antarctic ice

Totally unexpected, it’s far, far larger than any other known community of nesting fish

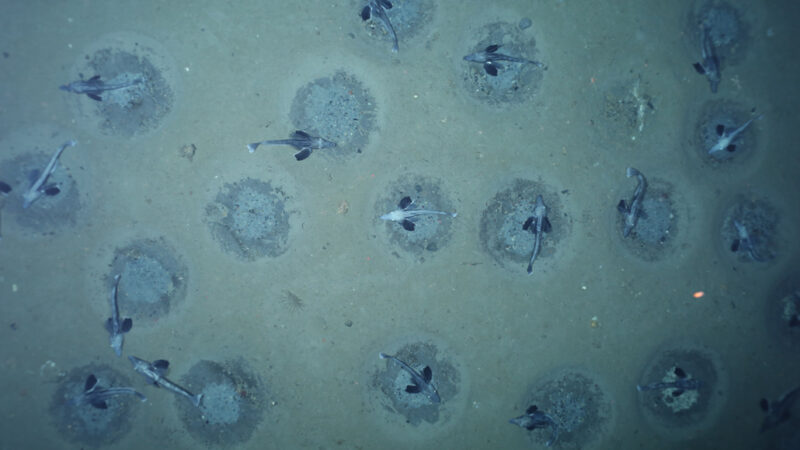

Jonah’s icefish (Neopagetopsis ionah) create circular nests with hard rock centers, where the fish can lay more than 1,700 eggs.

Alfred Wegener Institute, PS124 OFOBS team

By Jake Buehler

The world’s largest known colony of breeding fish has just been discovered off the coast of Antarctica. It’s some 500 meters (1,640 feet) below ice that covers part of the Weddell Sea. These fish are known as icefish. And this massive community of nests stretches across at least 240 square kilometers (92 square miles) of seafloor. That’s an area one-third larger than Washington, D.C.

Many fish create nests, from freshwater cichlids to stomach-free pufferfish. But until now, researchers hadn’t found many icefish nesting near each other — maybe just several dozen. Even the most social species of nesting fish had been found to gather only in the hundreds. The new one has an estimated 60 million active nests!

Autun Purser is a deep-sea biologist. He works at the Alfred Wegener Institute in Bremerhaven, Germany. He was part of a team that stumbled across the massive colony in early 2021. They were aboard a German research icebreaker, the Polarstern. The ship was cruising the Weddell Sea. That region lies between the Antarctic Peninsula and the main continent.

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

These researchers had been studying chemical links between surface waters and the seafloor. Part of that work involved surveying seafloor life. To do this, they slowly towed a device that recorded video as it was gliding just above the ocean bottom. It also used sound to map seafloor features.

At one site under the Filchner ice shelf — ice floating in the Weddell Sea — one of Purser’s teammates noticed something. Circular nests kept showing up on camera. They belonged to Jonah’s icefish (Neopagetopsis ionah). These fish are only found in the Southern Ocean and Antarctic waters. Traits they adapted to survive the extreme cold include the development of clear blood full of antifreeze compounds.

Half an hour after the nests began showing up, Purser came down to see the camera images. Amazed, he “just saw nest after nest the whole four hours of the first dive.” At once, he recalls, it appeared “we were onto something unusual.”

Massive nursery under ice

Purser and his colleagues made three more surveys in the area. Each time, kilometer after kilometer, they found more nests. Perhaps one of the closest comparisons to these icefish are the nest-spawning lake fish known as bluegills (Lepomis macrochirus). They can form breeding colonies that number in the hundreds, Purser says. But the Weddell Sea colony is at least several hundreds of thousands of times larger, the researchers say. That’s based on measurements showing about one icefish nest per four square meters (43 square feet) across hundreds of kilometers of territory. And each nest, guarded by an adult, may hold some 1,700 eggs.

Purser’s group described its unexpected find January 13 in Current Biology.

This colony is an “amazing discovery,” says Thomas Desvignes. He’s an evolutionary biologist at the University of Oregon in Eugene. He was especially struck by the extreme concentration of nests. “It made me think of bird nests,” Desvignes says. Cormorants and other marine birds “nest like that, one next to the other,” he says. With these icefish, “It’s almost like that.”

It’s not clear why so many icefish gather so closely to breed. The site seems to have good access to plankton. They would make good meals for fish hatchlings. The team also found a zone in the area with slightly warmer water. That might help the icefish home in on this breeding ground.

The nesting fish probably have a big and previously unknown impact on Antarctic food webs, the researchers say. For instance, they might be sustaining Weddell seals. Many of these seals spend their days on ice above the nesting colony. In the past, studies have reported these seals spend much of their time diving in waters above the nesting site.

Purser thinks that there may be smaller colonies of these icefish closer to shore, where there is less ice cover. It is possible, though, that most Jonah’s icefish rely on the one massive breeding colony. If true, they would effectively be putting all their eggs in one basket. And that “would make the species extremely vulnerable” to extinction, Desvignes says.

The new discovery of the massive colony is one more argument for providing environmental protections for the Weddell Sea, he says. Desvignes notes that it’s something that has been done for the nearby Ross Sea.

For now, Purser currently has two seafloor cameras at the colony site. They will remain there for a couple of years. Taking photos four times a day, they’ll watch to see if the nests are reused year after year.

“I would say [the massive colony] is almost a new seafloor ecosystem type,” Purser says. “It’s really surprising that it has never been seen before.”