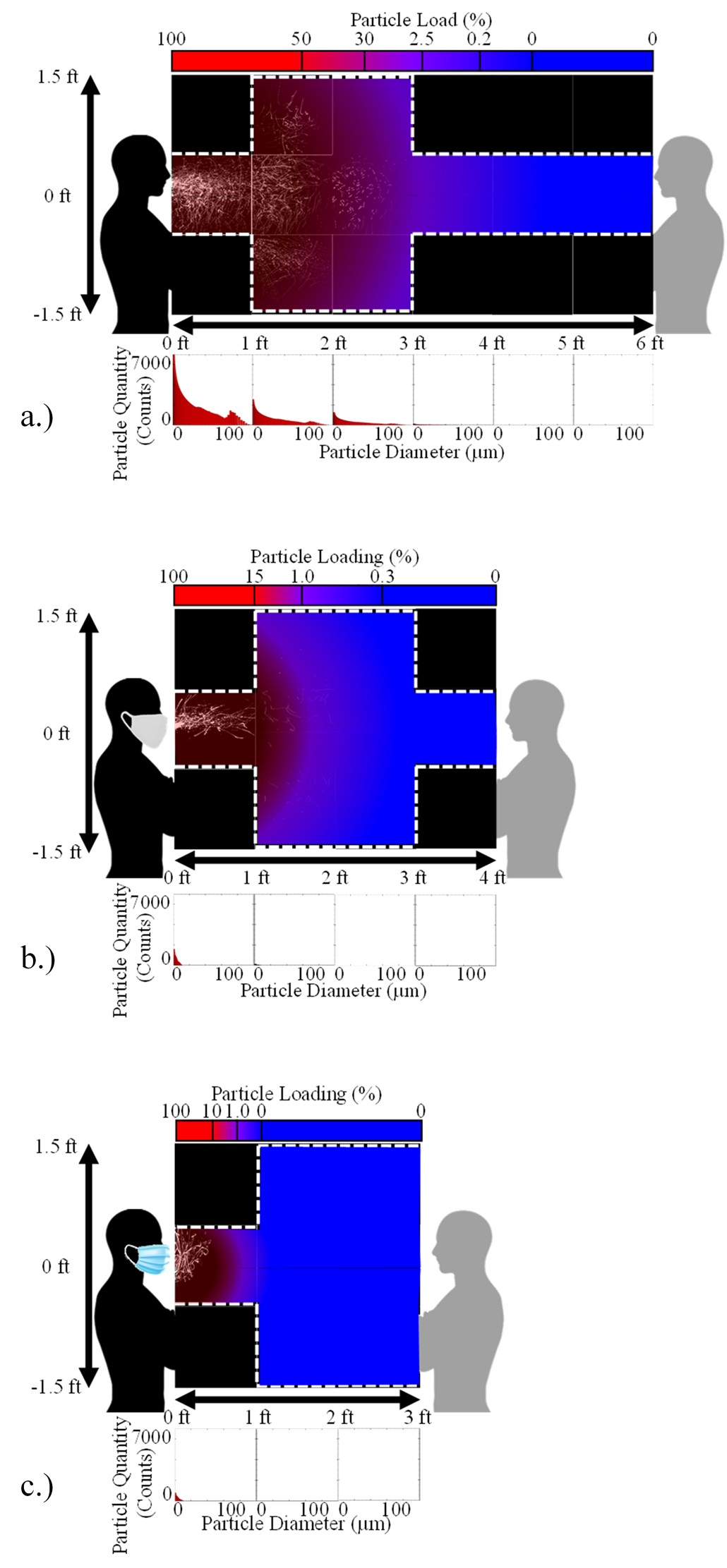

Analyze This: Masks cut the distance that spit droplets fly

Saliva droplets traveled farthest when coughing or speaking people weren’t wearing a mask

Speaking or coughing sends a spittle-filled jet from a person’s mouth. A mask, though, slows down that jet, cutting the distance spit droplets travel.

Rumi Fujishima/ DigitalVision Vectors /Getty Images

At this point in the COVID-19 pandemic, many people are tired of wearing masks. But masks really do help slash the distance virus-carrying spit flies, a new study finds.

“Early in the pandemic, we were all advised to be six feet away from each other,” says Kareem Ahmed. A mechanical and aerospace engineer, Ahmed studies how fluids such as air and water move. He works at the University of Central Florida in Orlando. “That was perplexing,” he says. When Ahmed and his colleagues observed a few individuals in the lab, they hadn’t seen saliva travel that far. And people vary in how far they send spit aerosols. These are the tiny droplets that move through the air when someone is coughing or talking.

The team set out to collect data that would suggest a safe distance for avoiding someone else’s spittle. The researchers measured the spit spray from the mouths of 14 people. In one set of experiments, each person spoke the same phrase: “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog into a field of pretty playful perpetually purple pandas.” That phrase contains all letters of the alphabet. And those “puh”, “ple” and “per” sounds make big droplets that tend to fly farther. In a second set of experiments, each person coughed. Study participants coughed or spoke with three masking conditions: no mask, a single-layer cloth mask or a disposable surgical mask.

The researchers shined a bright light where the people were speaking or coughing. That light bounced off the droplets, making their spread easier to see in video and images. The researchers also measured the size of the droplets. They compiled this data for all the participants and found that wearing a mask affected how far the droplets spread. Masks also reduced the total amount of aerosols that entered the air.

Speaking or coughing makes a jet of air come from a person’s mouth, Ahmed says. A mask slows down that jet and those airborne spit drops. But how well masks worked depended on their quality.

“For the cloth mask, we did not expect it to be performing so poorly,” Ahmed says. But the three-layer surgical masks performed surprisingly well. Still, both reduced the distance spit traveled by at least half, compared with no mask. Such data can help people decide what’s a comfortable distance to put between themselves and others.

The researchers shared their findings January 12 in The Journal of Infectious Diseases.

Data Dive:

- Put your hand in front of your mouth so it’s close but not touching. Say “the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog into a field of pretty playful perpetually purple pandas.” What does this feel like on your hand? On which words do you feel the most air hit your hand?

- Now put on a mask. Say the same phrase. How does it feel different?

- Make a table using data from the figure above. For each type of mask (or no mask), at what distance is the particle load 50 percent, 30 percent, 2.5 percent and 0 percent? How might you graph this data?

- Compare these distances. Divide the distance for 50 percent without a mask by the distance for 30 percent with a cloth mask. Divide the distance for 50 percent without a mask by the distance for 30 percent with a surgical mask. What does this tell you about how well the cloth and surgical masks work?

- Divide the distance for 0 percent particle load without a mask by the distance for 0 percent particle with a surgical mask. How much closer can someone be with a surgical mask and likely not be exposed to the other’s spit?

- Imagine that you are speaking with a classmate who has a cold. You don’t want to get that cold and want to avoid coming into contact with their spit. How close should you stand to your classmate? How close would you stand if they were wearing a surgical mask?