Americans tend to see imaginary faces as male, not female

It’s not yet clear why this gender bias exists

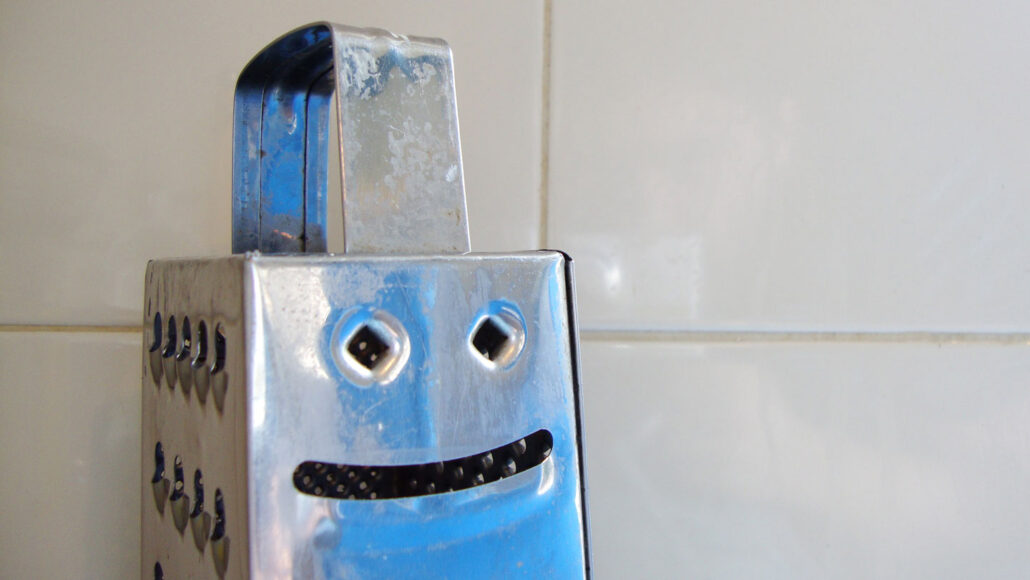

People sometimes see imaginary faces in everyday objects, such as the smiley face on this cheese grater. In a new study, these faces were more often seen as male than female by U.S. adults.

Paul David Galvin/Moment/Getty Images Plus

Have you ever seen the outline of a face in a cloud? Or perhaps in the pattern of your carpet? Or some other everyday object? This phenomenon is very common. It’s called pareidolia. Much is still unknown about how people perceive such imaginary, or “illusory” faces. But a new study has uncovered one curious detail. People are more likely to see illusory faces as male than female. Researchers shared that finding on February 1. It appeared in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The research was led by Susan Wardle. She works at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md. This cognitive neuroscientist is fascinated by illusory faces. “They’re an example of face perception that’s incorrect,” she says. “And often by studying the mistakes of our brain, we can better understand how it works.”

One day while looking at photos of illusory faces in the lab, Wardle wondered: “Where’s all the female faces?” Even though the faces appeared in nonliving objects with no gender, most appeared male to her.

Wardle was curious whether other people shared this bias. So she and her colleagues recruited over 3,800 people online. All were adults living in the United States. These volunteers viewed about 250 photos of illusory faces. The faces appeared in a variety of objects, from potatoes to suitcases. Participants labeled each one as male, female or neither.

Illusory faces were labeled male about four times as often as they were female. Both male and female participants showed that bias. About 80 percent of people labeled more images male than female. Only 3 percent judged more images to be female than male.

-

Patterns in everyday objects, from construction fixtures (one shown) to the clouds in the sky, can look like faces. S. Wardle -

People often perceive imaginary faces as having a gender. In a study with nearly 4,000 American adults, about 80 percent of participants labelled imaginary faces — such as the one in this slice of cheese — as male more often than female. Chris Baker -

Just 3 percent of survey participants labelled the faces, such as the one in this ice cream cone, as female more often than male. Chris Baker -

The new study suggests that Americans tend to see the basic pattern of a face, like the one on this basketball hoop, as male by default. This gender bias seems to arise early in life, appearing in children as young as about 5, more recent research by the same scientists found. Chris Baker

“We had a hunch that there would be a male bias,” Wardle says. “But I think we were surprised firstly by how strong it was. And also, how robust it is … we’ve replicated it in many experiments.”

In other experiments, Wardle’s team tried to learn why this gender bias might exist. In one test, the researchers showed people images of the same kinds of objects that were in the illusory face photos. But this time, the objects did not contain a facelike pattern. Participants labeled these images male and female about equally. This showed there was not something about the objects themselves that had made the illusory faces seem male or female. Computer models that searched the illusory face photos for “masculine” or “feminine” features — such as more angular or curved features — couldn’t explain the bias, either.

“There’s this asymmetry in our perception,” Wardle says. An illusory face is a very basic pattern of a face. Given such a basic pattern, “we’re more likely to see it as male,” Wardle says. “It requires additional features to see it as female.” This makes sense, she adds. Think of female emojis and Lego characters. They are often distinguished from male ones by extra features, such as bigger lips and longer lashes.

It’s not yet clear why people assume simple faces are male, Wardle says. But in a more recent study, her team found the same gender bias in kids as young as five. This suggests the bias arises early in life.

“I was not surprised that people would assign gender to illusory faces,” says Sheng He. But he was surprised by the strength of the gender bias that Wardle’s team discovered. He is a cognitive neuroscientist, too. He works at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing. Future studies, He says, could test whether the same bias exists among people in other cultures.