Clothes dryers may be a major source of airborne microplastics

Scientists had thought washing machines were, but dryers seem even worse

Washing — and especially drying — the laundry can have an environmental impact that goes far beyond the amount of water and energy used.

Maskot/DigitalVision/Getty Images

From the air to the oceans, tiny bits of plastic — some smaller than a bit of thread — swirl through our environment. Back in 2011, scientists identified one seemingly big contributor: lint released in water used to wash laundry. A new Hong Kong study now suggests that an even bigger culprit may be your humble tumble dryer.

For years, notes Kenneth Leung, microplastics researchers have been faced with a mystery: “Where are the atmospheric microplastic fibers coming from?” Leung studies ocean pollution at City University of Hong Kong.

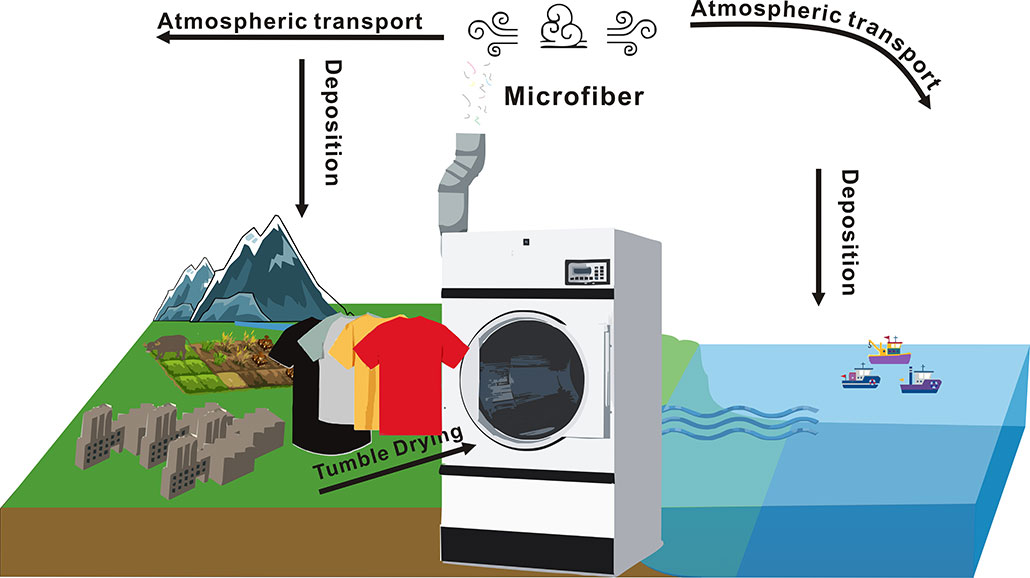

Tiny bits of plastic travel long distances on winds. They’ve been landing everywhere from the top of Mount Everest to the bottom of the ocean. Microplastic pollution is so widespread that people and animals can’t help ingesting it. That can harm wildlife and may pose risks to people, too. Yet for one in every five microplastic bits wafting through the air, Leung says, scientists “don’t have a clue” where they come from. “So now,” he says, “we’re putting the puzzle together.”

Clothing is one potentially big source. Through wear and tear, fabrics shed tiny fibers. That includes the fabric polyester. Since polyester is a type of plastic, its microfibers are microplastics.

Scientists had seen microplastic fibers in lint coming from washing machines. Sewage-treatment plants can remove many of these fibers from water. But airborne microplastics spewed from clothes dryers rarely make it to the sewage plant.

Leung says he realized the potential role of dryers after his machine’s exhaust pipe came loose from the window. It blew lint everywhere. “It was a disaster,” he recalls — and inspired his experiments. Those tests would show that dryers can release more than a half-million microfibers every 15 minutes. That includes bits of polyester and other fabrics like cotton. These can hurt small creatures that mistake the fibers for food.

An emerging focus on dryers

“This study is exactly what we hoped [for],” says Rachael Miller. She wasn’t part of the Hong Kong study, but does study microfiber pollution. She founded the Rozalia Project for a Clean Ocean in Burlington, Vt. Miller has also been inventing ways to capture laundry lint before it can pollute the environment.

In 2016, she noticed something weird while sampling Hudson River water in New York. She expected to find more microfibers in areas near lots of people. But microfiber levels were about the same everywhere, she says — “even where there are no people.”

She was part of a team that published those findings in the Marine Pollution Bulletin.

Miller wondered, “Could dryers be the source?” Microfibers could spread out in the air before settling into rivers. That may account for the uniform microfiber distribution. Curious, she went outside and checked her dryer’s exhaust.

The foliage nearby was covered in lint. Later, Miller teamed up with Kirsten Kapp of Central Wyoming College in Jackson. They dried fleece blankets in winter. After each load, they measured polyester microfibers on snow within nine meters (30 feet) of a dryer’s exhaust. Then they measured fibers emitted directly from the exhaust itself.

And they found plenty. But the amount varied with the type and age of a dryer. It also depended on how the dryer’s vent had been installed and differences in lint traps. (Lint traps are filters in dryers that are meant to capture lint before it escapes in exhaust.) Miller and Kapp shared their findings in 2020 in PLOS ONE.

Fabrics matter in lint spreading

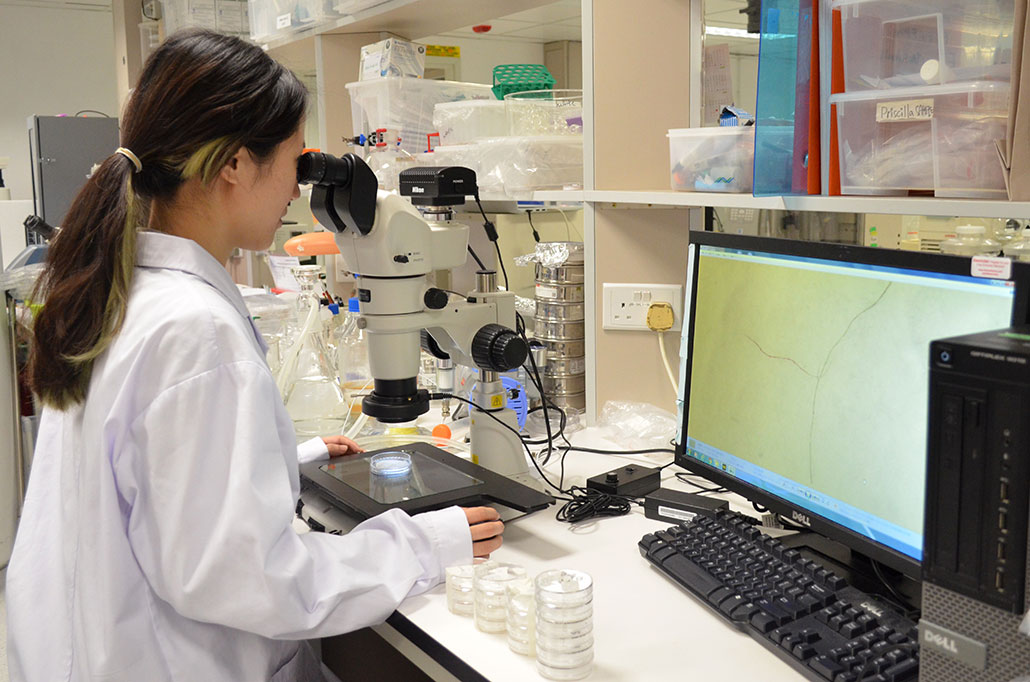

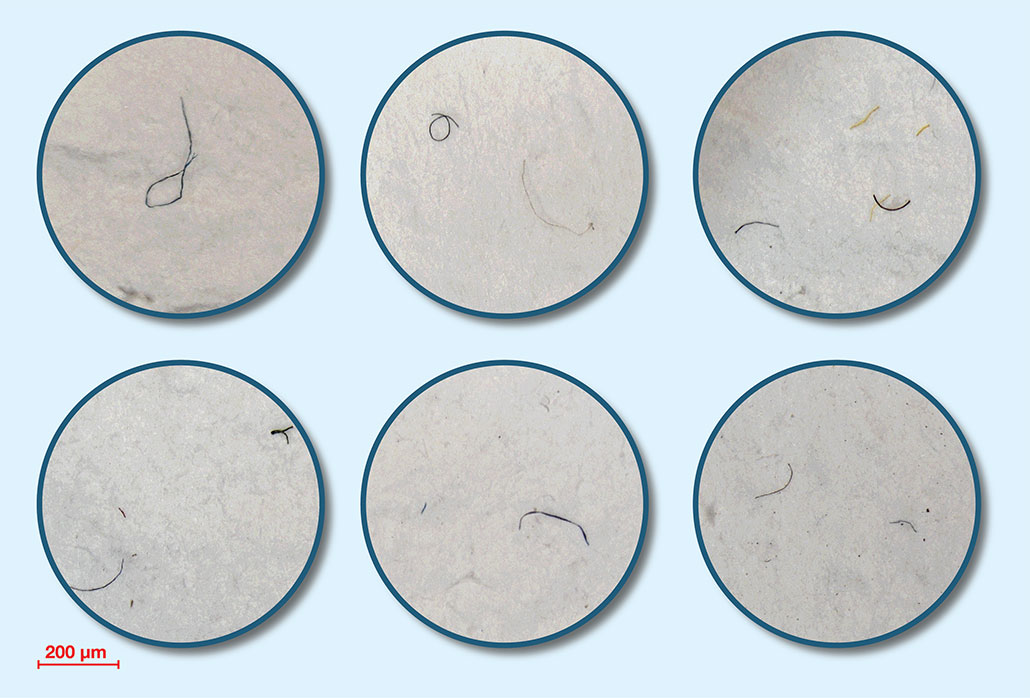

In the latest study, Leung and his team dried polyester and cotton fabrics in household dryers. They collected the lint released in the dryer exhaust and used wax to seal the fibers in petri dishes. Fibers shorter than 5 millimeters (0.2 inch) counted as “microfibers,” notes Kai Zhang. He’s another researcher on the team. The researchers double-checked their results with a spectrophotometer (SPEK-troh-foh-TOM-eh-tur). This machine identifies substances by measuring the amount of light they absorb at different wavelengths.

And “Bingo!” says Leung. The number of microfibers they tallied “is alarming.” Dryers produced more microfibers than washing machines — up to 40 times more. Using Canadian household tumble-dryer data, his team now estimates that each year a single household dryer can spew up to 120 million microfibers into the air.

“This answered our question,” Leung says, about where airborne microfibers are coming from. His team reported its findings January 12 in Environmental Science & Technology Letters.

Polyester produced more microfibers than cotton. And weirdly, cotton produced similar amounts of lint no matter how big the wash load. Both 0.5- and 2-kilogram (1.1- and 4.4-pound) loads of cotton shed similar amounts of microfibers. But with polyester clothes, large dryer loads released far more microfibers than small ones.

The reason is that not all cotton fibers become microfibers, the Hong Kong team shows. Cotton fibers often tangle, making bigger bits of lint. These heavier fibers, Leung says, “can’t leap up into the air.” In contrast, polyester’s sleek strands don’t clump. Unprotected, they simply break into tiny bits.

“This study is a great follow-up to ours,” Miller says. “They used different materials.” And stark differences emerged between those materials.

Knowing how microplastics get into the air is the first step to preventing this pollution — which shows up even in human poop. These bits of trash may be unhealthy for reasons besides their plastic content, too. In water, plastic wastes often become protective sites on which microbes and algae anchor themselves. Leung now wonders whether plastic lint in the air also provides an “anchoring point for microbes.” If this helps them survive, these lint bits might become home to germs with antibiotic-resistant genes.

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

What can we do?

Several years ago, Miller invented a device that collects fibers during laundering. It tangles up lint in much the same way cotton does. When added to a washing machine, that lowers the release of lint. Researchers at the University of Plymouth, in England showed this in a 2020 study. A Canadian team has been testing another system. That one filters fibers from wash water.

Dryers already come with lint traps. But as the Hong Kong data show, these still let plenty of fibers escape. Better filtering should be possible, Leung notes. “But the engineers cannot achieve this without compromise.” Extra filters mean dryers have to work harder. And if people don’t understand the eco-friendly reasons for the extra energy and costs, they might not support it.

The real take-home message, Miller believes, is how connected we all are to the natural world. “When you pour something down your drain, it doesn’t really go away,” she says. “‘Away’ is not really away.” It comes back to you. Perhaps, one day, in your drinking water.