Like bloodhounds, worms are sniffing out human cancers

Tiny worms and breath analyzers could screen for disease while it’s early and treatable

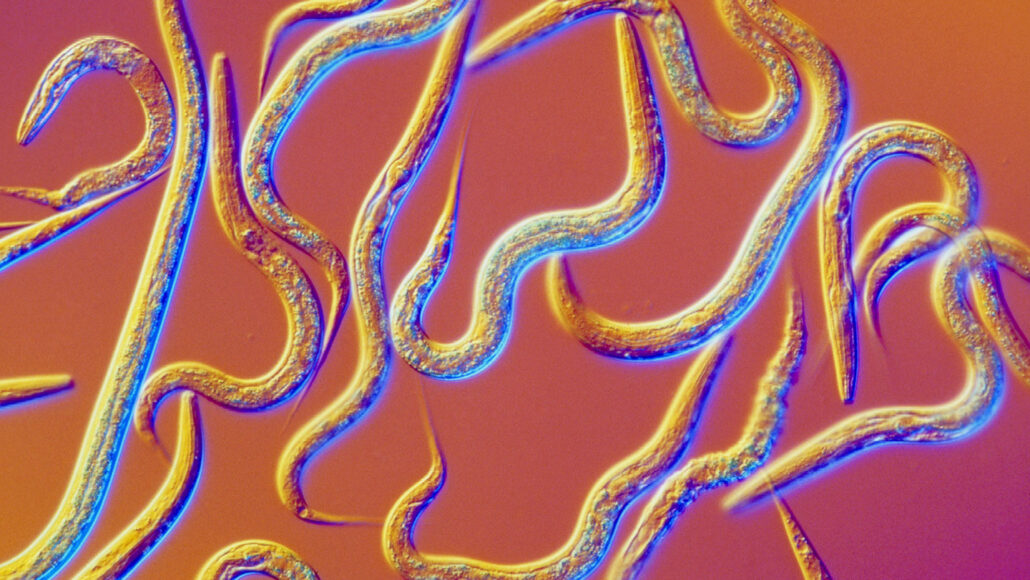

This microscopic image shows Caenorhabditis elegans nematodes, small worms being used in a new system to sniff out cancer.

Sinclair Stammers/Science Source

Strange as it may sound, worms could someday play a key role in fighting cancer.

Lung cancer cells seem to smell yummy to one species of little worm. Now, scientists are using that allure to build a squirmy new tool to detect cancer. The researchers hope this new “worm-on-a-chip” device will one day provide an easy, painless way to screen for early disease.

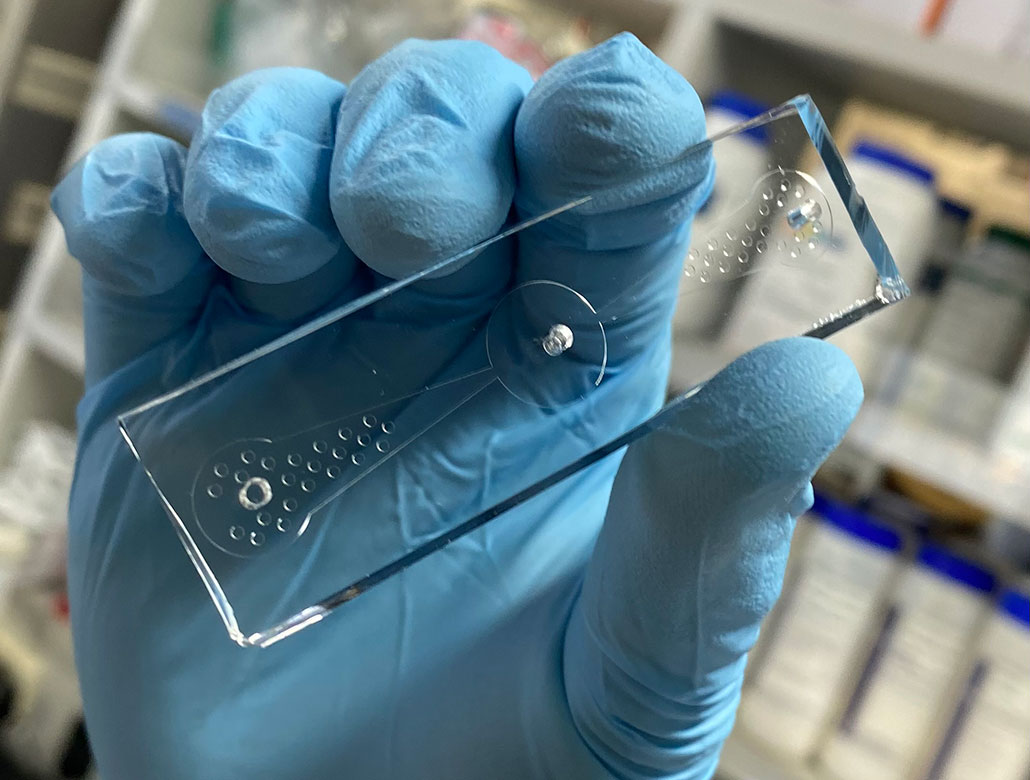

The cancer-seeking worm in question is the common roundworm, Caenorhabditis elegans. At just about one millimeter (0.04 inch) long, C. elegans is easy to fit on a handheld chip. To build that chip system, researchers crafted what looks like a microscope slide. It has three large indents, or wells. Healthy human cells get placed in a well at one end. Lung cancer cells go in a well at the other end. The worms go in the middle well. From there, they can sniff the cells at either end. In experiments, hungry worms tended to wriggle toward the end containing diseased cells.

It’s been reported “that dogs can sniff out people who have lung cancer,” says Paul Bunn. He’s a cancer researcher at the University of Colorado in Aurora who was not involved in the work. “This study,” he says, “is another step in the same direction.”

Each chip employs some 50 worms. “About 70 percent of the worms move toward the cancer,” says Shin Sik Choi. He is a biotechnologist that helped develop the worm-on-a-chip system at Myongji University in Seoul, South Korea. With training, Choi suspects the worms’ ability to sniff out cancer can be increased.

The Seoul-based team debuted its new worm-on-a-chip on March 20 at the spring meeting of the American Chemical Society. It was held in San Diego, Calif.

Wriggly super sniffers

No one can read a C. elegans worm’s mind. So, it’s impossible to say for sure why these tiny critters find cancer cells appealing. But Choi thinks scent is a pretty safe bet. “In nature,” he explains, “a rotten apple on the ground is the best place where we are able to find the worms.” And cancer cells release many of the same odor molecules as that rotten apple.

C. elegans has a pretty keen sense of smell, says Viola Folli. She studies neuroscience at the Sapienza University of Rome in Italy. Like the Korean team, she investigates C. elegans’ cancer-sniffing prowess. And she’s using what she learns to develop a cancer screening sensor. Although these worms can’t see or hear, Folli notes, they can smell about as well as dogs. In fact, C. elegans has about the same number of genes for chemical-sensing as mammals known for their great sense of smell, such as dogs or mice.

That’s pretty impressive, considering C. elegans boast only 302 nerve cells in its entire body — while the human brain alone packs about 86 billion.

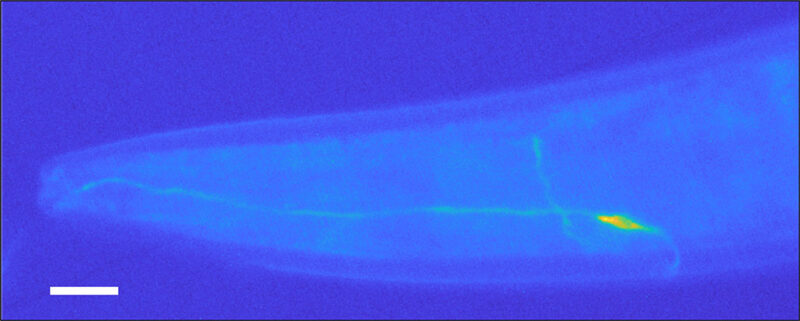

The worms’ simplicity has even allowed scientists to pinpoint the exact nerve cell that reacts to cancer cell aromas. Enrico Lanza, a physicist who studies neuroscience with Folli, did this by genetically tweaking some of the wigglers so that when a specific neuron got activated, it lit up. He then exposed the worms to diseased cells and examined them under a microscope, looking for glow-in-the-dark cells.

“C. elegans is transparent,” Lanza says. “So if something lights up inside [it]…you can detect it from the outside.” And something did light up — a single, radiant neuron located at one end of C. elegans. Lanza snapped a picture.

But what scents wafting off cancer cells make C. elegans’ nerve cells light up like this? Choi thinks his team may have pinpointed some of the compounds responsible. Those chemicals are known as volatile organic compounds, or VOCs — and they’re emitted by cancer cells. One that might entice C. elegans is a floral-scented VOC known as 2-ethyl-1-hexanol.

To test this idea, Choi’s team used a special strain of C. elegans. These worms had been genetically tweaked so that they lacked receptors for 2-ethyl-1-hexanol odor molecules. While normal C. elegans preferred cancer cells over healthy ones, genetically modified worms did not. This hinted that 2-ethyl-1-hexanol plays a key role in drawing worms to diseased cells.

This finding “makes perfect sense, because we know that cancers put out VOC signatures,” says Michael Phillips. He did not take part in the research. But he is developing cancer screening tests at Menssana Research in Fort Lee, N.J. Some of Phillips’ recent research has shown that VOCs in breath can help predict risk of breast cancer. That study appeared in Breast Cancer Research and Treatment in 2018.

Scouting for cancer

C. elegans’ ability to detect cancerous cells in the current worm-on-a-chip system is a good start. But now, Choi wants to see whether these worms can sniff out cancer when not directly exposed to diseased cells. Perhaps the worms could pick up a whiff of cancer-emitted VOCs in saliva, blood or urine. Doctors could use such a test to screen for lung cancer without having to sample cells from a patient.

Phillips’ research on cancer-related VOCs in breath suggests this idea has promise. Folli’s research does, too. Last year, her team reported that C. elegans preferred urine from patients with breast cancer over healthy people’s pee. That research appeared in Scientific Reports.

Such non-invasive tests could give doctors an edge in fighting cancer. Many lung-cancer patients, for instance, are not diagnosed before their disease has spread and become hard to treat. Some screening tools — especially CT scans — can detect lung cancer early. But the scans’ X-rays bring new problems. “The more CT scans you get,” Bunn says, “the more radiation you get.” And that radiation can itself lead to cancer. That’s why doctors don’t want to do these scans unless they suspect disease.

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

A worm-on-a-chip spit or urine test could provide a safer alternative. “Wouldn’t it be nice to have [such] a screening test?” Bunn says. “Even if it’s not as accurate as a CT scan?” At the very least, it might point to who might benefit most from those CT scans.

Phillips agrees. He uses his breath analyzer — BreathX — in the United Kingdom to screen for cancer. He says that different cancer cells release a different mix of VOCs. Each pattern is like a fingerprint. Some other diseases also release VOCs. Using exhaled breaths, “We see completely different fingerprints for breast cancer compared to tuberculosis,” Phillips says. The VOC fingerprint, he says, changes with each disease.

Neither BreathX nor the worm-on-a-chip device are intended to diagnose cancer. “I would never tell a woman that she’s got breast cancer based on the results of a breath test,” Phillips says. Or, he adds, a worm-on-a chip test. The value of this tech, he believes, is to provide a harmless, low-cost way to screen for people at high risk of disease. Those tools could help find cancer early, when it can still be fully removed or effectively treated.

This is one in a series presenting news on technology and innovation, made possible with generous support from the Lemelson Foundation.