Here’s why cricket farmers may want to go green — literally

The insects grown under this colored light showed lower rates of injury and death

Many people find eating insects, like these crickets, quite a treat. That’s why farmers in Thailand and elsewhere raise them as mini livestock. But the insects can hurt each other in captivity. Two teens now report a way to minimize those casualties.

pong-photo9/iStockphoto/Getty Images Plus

By Anna Gibbs

ATLANTA, Ga. — Crickets are valued protein in some parts of the world. But raising crickets as mini livestock has its challenges, two teens learned. Their solution won these young scientists from Thailand a spot as finalists at the 2022 Regeneron International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF) earlier this month.

Jrasnatt Vongkampun and Marisa Arjananont first tasted crickets while roaming an outdoor market near their home. As food lovers, they agreed the insect treats were delicious. This led the 18-year-olds to seek out a cricket farm. Here they learned about a major problem faced by the cricket farmers.

Those farmers tend to rear groups of these insects in close quarters. Bigger crickets often attack the smaller ones. When attacked, a cricket will amputate its own limb to escape the clutches of that predator. But after surrendering a limb, this animal will often die. And even if it doesn’t, losing a leg makes the animal less valuable to buyers.

Now, these two seniors from Princess Chulabhorn Science High School Pathumthani in Lat Lum Kaeo report finding a simple solution. They house their animals in colored light. Crickets living in a green glow are less likely to attack each other. The insects also suffer lower rates of limb amputations and death, the young scientists now report.

The advantage of going green

The teens left the cricket farm with a few hundred eggs of the species Teleogryllus mitratus. Jrasnatt and Marisa were determined to solve the leg-abandoning problem. After some research, they learned that colored light can influence the behaviors of some animals, including insects. Might colored light cut the risk of cricket tiffs?

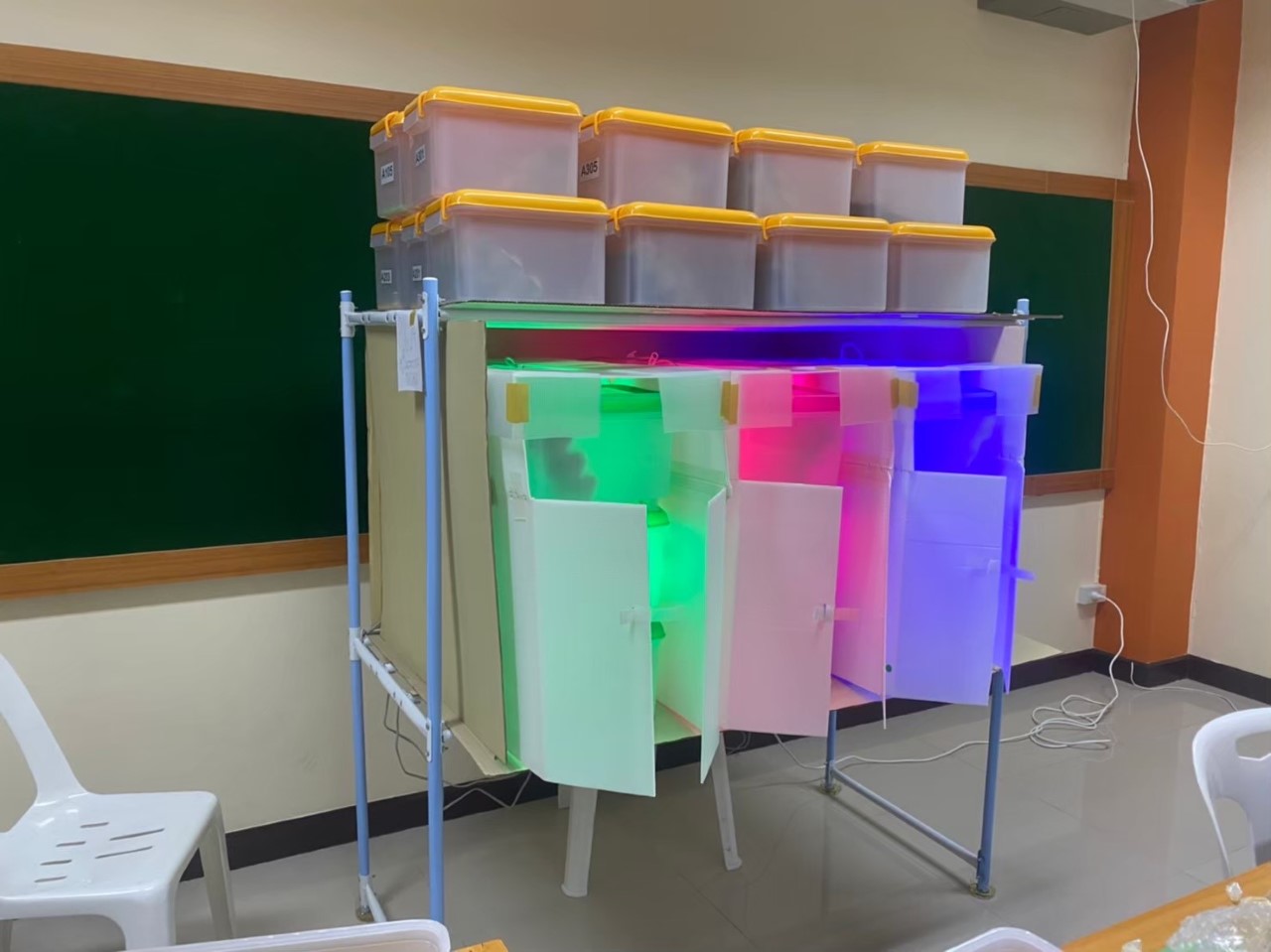

To find out, the researchers transferred batches of 30 newly hatched larvae into each of 24 boxes. Egg cartons set inside offered the little animals shelter.

The crickets in six boxes were exposed only to red light. Another six boxes were lit with green. Blue light illuminated six more boxes. These three groups of insects spent daytime hours throughout their lives — about two months — in a world bathed in just one color of light. The last six boxes of crickets lived in natural light.

Caring for crickets

Jrasnatt (left) is shown preparing cricket enclosures with egg boxes as a shelter. Marisa (right) is seen with her cages of crickets in a school classroom. The teens kept track of how many crickets lost limbs and died over the course of two months.

Care for the crickets was a full-time job. Like humans, these insects prefer about 12 hours of light and 12 hours of dark. The lights weren’t automatic, so Jrasnatt and Marisa took turns turning the lights on at 6 a.m. every morning. When feeding the tiny animals, the teens had to work quickly to ensure crickets in the colored-light groups got as little exposure to natural light as possible. In short order, the girls became fond of the crickets, enjoying their chirping and showing them off to friends.

“We see they’re growing every day and take notes on what’s happening,” says Marisa. “We’re like the parents of the crickets.”

Throughout, the teens kept track of how many crickets lost limbs and died. The share of crickets with missing limbs hovered at about 9 in every 10 among those living in red, blue or natural light. But fewer than 7 in every 10 crickets who grew up in a world of green lost legs. Also, the survival rate for crickets in the green box was four or five times higher than in the other boxes.

Why might green be so special?

Crickets’ eyes are adapted to only see in green and blue light, the teens learned. So, in red light, the world would always look dark. Without being able to see, they are more likely to bump into each other. When the crickets come closer to each other, explains Jrasnatt, “that will lead to more cannibalism.” Or attempted cannibalism, which results in crickets losing limbs.

Crickets are more attracted to blue light than green light, which pulls them closer together and leads to more fights. In the green light box — the hue of life under leaves — the crickets were most likely to mind their own business and avoid scuffles.

Creating a green-light world for crickets is a solution that could be brought to the farms. Jrasnatt and Marisa are already in talks with the farmers from whom they bought their cricket eggs. Those farmers plan to try out green lighting to see if it will boost their profits.

This new research won Jrasnatt and Marisa third place — and $1,000 in the Animal Sciences category — at the new competition. They were vying with some 1,750 other students for nearly $8 million in prizes. ISEF has been run by Society for Science (the publisher of this magazine) since the annual competition started in 1950.