Teens’ new tech would send alerts to reduce preventable deaths

The devices can speed up responses for everything from pool accidents to combat injuries

Drownings are the leading cause of injury-related deaths among U.S. children one- to four-years old. A Louisiana teen’s new system would alert pool owners when a child falls into an unguarded pool. It’s one of several life-saving devices to win awards at the 2022 Regeneron ISEF competition.

Mikel Taboada/Moment/Getty Images Plus

By Anna Gibbs

ATLANTA, Ga. — It’s an all too common story: A young child wanders off during a party and falls into a backyard pool. No one notices she’s missing — until it’s too late. When Grayson Barron learned of such a tragedy in a friend’s neighborhood, the 18-year-old immediately jumped into problem-solving mode. The new pool alarm system he’s just developed sends out several types of warnings when someone or something splashes into an unguarded pool.

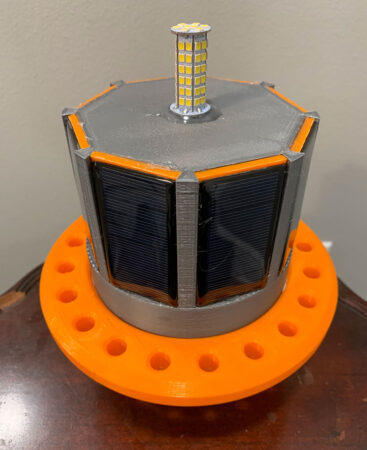

Grayson calls his floating system “The Buoy.” The idea is to turn it on when no one is using the pool. A large splash will trigger its built-in sensors to send out a series of alerts — a flashing light, an alarm that sounds like a loud doorbell and a text to the owner’s mobile phone.

“You could be on the other side of the world and know if somebody has just jumped in your pool,” says the inventor, a senior at John Curtis Christian School in River Ridge, La.

Grayson showcased his project here, in Atlanta, last month at the 2022 Regeneron International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF). Other finalists also presented new ways to warn people of potentially life-threatening problems — including overheating cars and isolated soldiers who get wounded in combat. The new devices offer novel ways to deal with these out-of-sight emergencies.

Making splashes heard round the world

Grayson’s is not the first pool alarm. But the teen says others all have drawbacks. Some are very costly. Other floating alarms can become stuck in corners of a pool or get off-kilter. He wanted a low-cost option that was reliable. Grayson 3-D printed the main part of his device, then attached sensors. They detect its orientation and movements. He then equipped the device with a light, a speaker and a wireless network that can send texts. A battery, which is hooked up to solar panels, keeps the system charged for months. An anchor keeps the buoy upright and in place.

While tricky to design, the new system “is so easy to use,” says Grayson. “All I do is turn it on and toss it in.” After that, he says, it just “does its thing.”

Grayson plans to teach future versions of his device to identify the source of any unexpected waves. Then the alarm might tell the difference between a basketball, for example, and a child or small dog. He also wants to add cameras. These could send an image of the splash-maker to a phone or home security system.

The final product would likely cost around $450. But Grayson plans to reach out to insurance companies to help make it affordable for all. When it comes to the risk of drowning in pools, he says, “everyone has a connection to it.” Indeed, drownings are the second leading cause of injury-related deaths among children 17 and under — and the leading one among kids one- to four-years old.

Grayson’s project won him second place and a $2,000 prize in ISEF’s engineering technology category.

Preventing heatstroke in cars

Three young researchers in Jordan had heard tragic stories about local kids who died after being left in a car that was out in the sun. Children’s bodies heat up three to five times faster than do adults’. So young kids can develop lethal heatstroke in a matter of minutes.

Areen Alashmawy learned about one such local tragedy from a teacher. Areen is a sophomore at King Abdullah II School for Excellence in Aqaba. Her teacher asked, Why don’t we have a solution for this problem? “I just kept thinking about that,” says Areen, now 16.

In Amman, Jordan, 17-year-old Ayah Alkatib was wondering the same thing. “It’s a real problem,” she says. “It’s happening everywhere.”

Ayah’s research turned up some distressing statistics: Every 10 days in the United States alone, a child dies in a car from heatstroke. More than half of these deaths involve children whose parents had forgotten they were in the vehicle.

Ayah, a junior at Jubilee School, started working on a heatstroke-warning system. Areen and her friend Sara Altarawenh, also 16, did too. After their projects won their local science fairs, Areen and Sara joined forces with Ayah to create an improved device to show off at ISEF.

Nicknamed “Safe in Vehicle,” this device measures temperatures and levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) in a car. Its weight sensors can detect how many people are inside the vehicle. The device alerts caregivers of concerning car conditions by sending text messages to their cell phone. But the device also works as a monitor. When linked to a mobile app, people can view a car’s indoor temperature and CO2 levels from afar.

This new device also provides a potential solution. When the indoor temperature or CO2 hits some threshold level, the device triggers motors to lower a car’s window by a several centimeters (a few inches) and turn on a fan. That could provide life-saving relief until help arrives.

The most complicated part was coding the text-messaging system, Ayah recalls. It took as long to code just this part as it did to code the operation of all the device’s sensors.

The three young researchers also struggled to find support for their work. Areen and Sara worked on their project at home and in the park because they couldn’t work at the school’s lab. And when the teens reached out to engineers and doctors for advice, those adults dismissed their idea as too challenging. The young researchers are now proud to have proven those naysayers wrong.

The team hopes their appearance at ISEF can get their device the attention it needs to eventually get it to market. Their hope for this system, says Areen, is that someday “you buy the car, and it’s already there, like the airbag.” They also imagine a future version that could send an emergency alert to 911 and use GPS to identify the vehicle’s location.

A device like this can’t come soon enough. “Because of global warming, [heatstroke] cases are going to increase,” Sara says. “This device is going to be more important with time.”

Detecting injuries in the field

Vivek Sandrapaty has been pondering a very different problem. He had heard about a police officer who was shot and died before he was found. Vivek was especially troubled that the officer might have survived had aid come sooner. Vivek’s solution: a smart uniform that can detect when someone has been wounded.

The 17-year-old from West Port High School in Ocala, Fla., embedded fabric with threads that conduct electricity. These special threads crisscross the material. They’re hooked up to transistors, which direct a small electric current through them. Cutting any of the conducting threads — by a bullet or knife, for instance — will change the flow of current. That will show up on a computer screen to note where, exactly, on the fabric the current flow has changed. This pinpoints the injury. The fabric also could include a GPS system to share the injured person’s location.

If there were many injured people, the system might also alert a medical team on who needed help first. Where the injured are unable to radio in their status, the system could show who was shot in the chest, for instance, versus in the leg. Now medics would “know to help the guy who was shot in the chest first,” says Vivek. He explains it could work “like a triage system, basically.”

His latest work is figuring out how to reduce false alarms that might occur when threads break from simple wear-and-tear. Vivek hopes this setup might someday be built into the uniforms of all people who work on the front lines, such as police officers and military troops. The teen’s work won him fourth place at ISEF — and a $500 prize — in the embedded systems category.

The five teens profiled here were among more than 1,100 high school finalists from around the world at this year’s Regeneron ISEF. Another 500 students competed virtually. ISEF, which doled out nearly $8 million in prizes this year, has been run by Society for Science (the publisher of this magazine) since the annual competition got its start in 1950.