Western wildfire smoke poses health risks from coast to coast

The fires have sent bad air to the East, boosting emergency room visits there — and deaths

Western wildfires, like this 2018 Camp Fire in Paradise, Calif., devastate local communities. Their smoke also travels to cities out East. Researchers are beginning to study the health effects for people far downwind of the fires.

Josh Edelson/AFP via Getty Images

By Megan Sever

After a relaxing July day at the Jersey Shore in 2021, Jessica Reeder and her two children headed home to Philadelphia. As they crested a bridge into Pennsylvania, they were greeted with a hazy, yellow-gray sky. It reminded Reeder of what she often saw growing up in Southern California. Smoke clouded the sky on days when fires scorched dry canyons.

Smelling smoke, Reeder worried about her asthma and her kids. So she flipped a switch in her car to recirculate the inside air. She didn’t want to draw in any of the smoke. Once home, her family closed all the windows and turned their air purifiers on high.

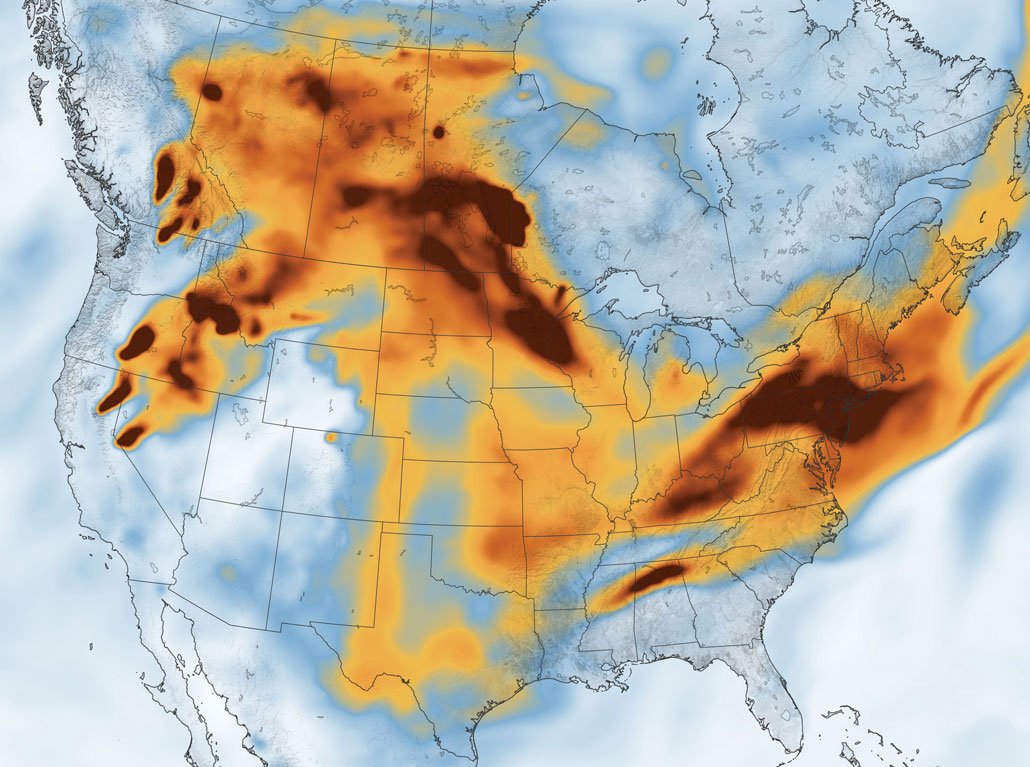

The smoke they were trying to avoid had traveled from fires raging on the other side of the continent. It was wafting in from California, from the Pacific Northwest and from western Canada. Smoke levels in Philadelphia didn’t come close to the record-breaking pollution then plaguing West Coast cities. Still, it was bad. It triggered bad-air warnings, and not just for people with asthma or heart disease.

In North America, most large wildfires occur in the western states and Canada. But smoke generated in the West doesn’t stay there. It tends to travel east. Within days, it can dirty the air in the Midwest and even East Coast towns. (Some of this smoke can cross the Atlantic to pollute European skies, as well.) Today, most asthma-related U.S. deaths and emergency-room visits from wildfire smoke occur in Eastern cities. That’s according to a study in the September 2021 GeoHealth.

The big problem comes from tiny aerosols — bits of ash, other particles and droplets in the air. Scientists refer to this mix as particulate matter, or PM. The smaller the PM, the longer it can stay in the air. And the longer it floats, the farther it can travel.

An especially worrisome size is known as PM2.5. These bits are no more than 2.5 micrometers wide. That’s about one-thirtieth the width of a human hair. These aerosols are so small that they can be inhaled deeply into the lungs. PM2.5 has been linked with breathing-related injury, diabetes and heart disease. These aerosols also can trigger asthma and other chronic conditions in otherwise healthy people. And especially in kids, smoke-related aerosols can provoke flare-ups of eczema, an intensely itchy skin disease.

Over the last few decades, U.S. clean-air laws have cut down on emissions of PM from industrial sources. That’s helped clean the air in many cities. But these rules don’t cover PM from wildfire smoke. Especially worrisome: Recent studies have shown that aerosols from wildfires may be more toxic than industrial sources of these pollutants. What’s more, exposures to wildfire smoke have been growing — in many places, by a lot.

So far, much of the science on how wildfire PM2.5 can sicken has focused on people exposed to smoke near fires in the U.S. West. Now, researchers are turning their attention to how this smoke may be affecting people as far away as the East Coast. One thing is clear: With climate change increasing the intensity and frequency of wildfires, people across North America need to be concerned about the health impacts of this smoke, says Katelyn O’Dell. An atmospheric scientist, she works in Washington, D.C., at George Washington University.

Bad air travels

Federal rules set limits on allowable levels of PM2.5 from things like factories, electric-power plants and gas- and diesel-powered vehicles. These rules have done “a really good job” in cutting air pollution in the last couple of decades, says Rosana Aguilera. She’s an environmental scientist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. It’s in La Jolla, Calif. PM2.5 levels in air had been dropping — at least until recently.

But Western wildfires have been growing more frequent. They’ve also become larger and more severe. Their smoke has begun erasing some of the gains made in cutting industrial pollution, says Rebecca Buchholz. She’s an atmospheric chemist. She works at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo.

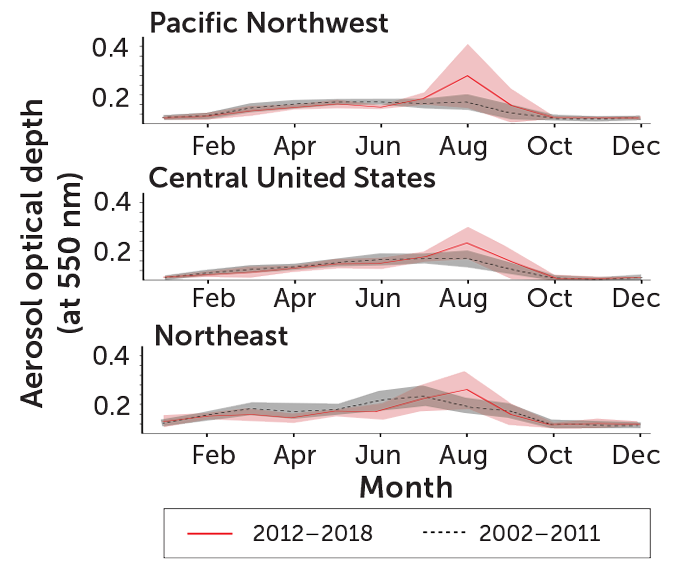

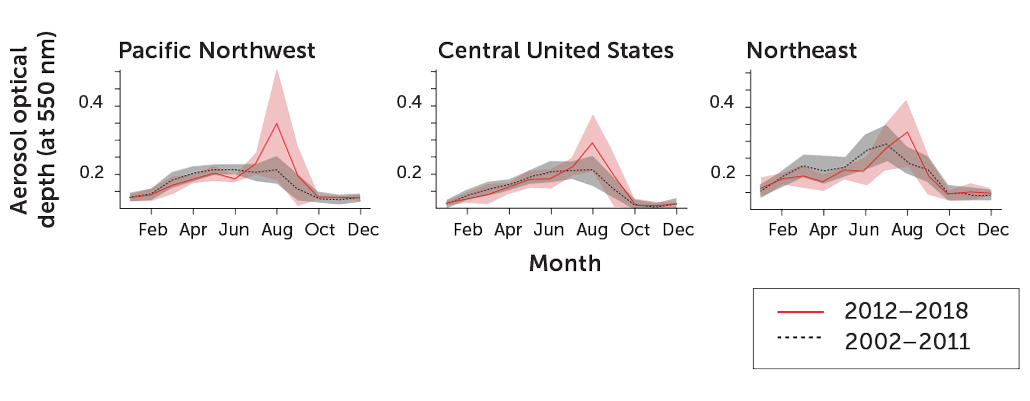

In the Pacific Northwest, fires are “driving an upward trend” in PM pollution. It’s something Buchholz and her colleagues described April 19 in Nature Communications. That smoke tends to peak in August. It’s when dry weather hits and fires tend to spike. At this dry time of year, the atmosphere’s ability to clean itself — through rain, for example — is limited. Such a late-summer spike in air pollution is new, Buchholz adds. It’s really showed up in the last 10 years.

And, as Reeder’s family witnessed last year, wildfire smoke is moving East. There, it can cause PM2.5 levels to skyrocket, Buchholz and her colleagues found. Pacific Northwest wildfires now threaten the health of some 23 million people in the Central United States and 72 million more in the Northeast.

Since at least 2019, Western fires have also been pushing summer PM2.5 to unhealthy levels in much of Minnesota. One 2018 study showed that between June and September, wildfire smoke now dirties the state’s skies for eight to 12 days each month.

How far and where that smoke travels depends in part on the weather. How high it goes into the sky also matters. The stronger and hotter the fire, the longer the smoke can last and the farther it can fly. Last year, distant wildfires badly polluted the air in the Great Plains. That’s a region stretching from Montana and Minnesota in the north down to New Mexico and Texas. But the smoke didn’t stop there. Some continued to move east, polluting the air from New York City to Washington, D.C.

Because of that, New York City saw some of its worst air pollution in 20 years. Western and Canadian wildfires spawned two “code red” days in Philadelpha, too — meaning its air was unhealthy for all.

Air safety yardstick

The Air Quality Index, or AQI, ranges from 0 to 500. This measure of health risk is based on what’s polluting the air at a given time. Ground-level ozone, particulate matter (including PM2.5), carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide and nitrogen dioxide are the primary pollutants used to set a code’s ranking. Code orange (above a score of 100) is unhealthy for people with heart and lung disease or diabetes, for children and for the elderly. Code red and above (over 150) is unhealthy for all.

Human impacts

Smoke from the West is already causing measurable harm in the East, says O’Dell. She led that 2021 study in GeoHealth. As part of it, she and her team reviewed smoke PM2.5 and health data from 2006 through 2018. These data showed that asthma episodes triggered by wildfire smoke send more people in the East to emergency rooms — and sometimes overnight hospital stays — than out West. That was true for 11 of the 13 years they studied.

Over that time, roughly three in every four asthma-related ER visits, hospitalizations and deaths occurred east of the Rocky Mountains. In fact, the study found about 4,600 of the estimated 6,300 excess deaths from these asthma complications occurred in the East.

Smoke affects so many people there, O’Dell explains, mainly because that’s where most people live. Some 64 million people live west of the Rocky Mountains. Three and a half times that many live east of the Rockies. The rate of smoke-related asthma deaths is higher in the West. But since so many more people live east of the Rockies, the total number of asthma deaths from wildfire smoke is higher there.

August peaks

Aerosol pollution — including that in the PM2.5 range — has been increasing since 2002 due to Pacific Northwest wildfires. That aerosol increase has climbed especially since 2012. This pollution tends to spike in the warm, dry summer months. As smoke wafts east, similar smaller spikes show up in the Central United States and northeastern North America.

North American seasonal atmospheric aerosol levels, by region

Are wildfire aerosols especially toxic?

Smoke can change as it moves through the air, both in volume and in the chemicals that make it up. Fires emit some of these aerosols directly. Other pollutants may develop as particles and trace gases from the fires react chemically in the presence of sunlight, Buchholz explains. Such reactions can lead to the creation of additional PM2.5 aerosols downwind of fires. How these aerosols change — through interactions between fire pollutants and between fire and human pollution — “is a really active area of research,” she says. And, she adds, “it’s super complicated.”

Jennifer Stowell works at Boston University’s School of Public Health in Massachusetts. As an environmental epidemiologist, she’s sort of a disease detective. Emerging research suggests that the PM2.5 aerosols produced by wildfires can be unusually hazardous, she says.

One 2019 study compared small aerosols emitted by fires in South America’s Amazon forests to those from sources such as cars. Nga Lee Ng, an atmospheric chemist at Georgia Tech, was part of the international team that conducted this work. Her group showed that smoke aerosols are more toxic than the aerosols typically polluting city air. They caused about five times as much “stress” to cells from molecules known as oxidants, Ng says. Oxidants can damage cells, including their DNA. (By the way, such oxidants also are behind some of the cellular harm, including inflammation, seen in smokers and vapers.)

As smoke aerosols move through the air, they also age. This isn’t a good thing. The changes that occur over time seem to make them more toxic, Ng explains. Reactions oxidize fire aerosols as those particles encounter sunlight and other pollutants in the air. That’s partly how the aerosols become more harmful.

Research like this suggests that studies of PM2.5 collected near wildfires in the West may underestimate the potential risk of those aerosols to people in the East, says Daniel Jaffe. He’s an atmospheric chemist at the University of Washington Bothell. He notes that even though the aerosol concentration drops as the pollution moves great distances, “the health effects per gram [of this pollution] are greater” than they were in the beginning.

These PM2.5 aerosols are so small that they can move through the lungs and into the blood. That’s something that toxicologist Matthew Campen worries about. He works at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque.

Wildfire smoke can harm the lungs by inflaming lung tissues. But in one study in mice, Campen’s team found that inflammation in the lungs was modest compared with the serious inflammation they witnessed in the brain. Given what’s known about how damaging smoke PM2.5 can be in the lungs, to find even greater effects on the brain is troubling, he says.

That brain inflammation happens quickly. It showed up within 24 hours of exposure to PM2.5 smoke aerosols. That’s what a team of researchers reported in the March Toxicological Sciences. Here, the aerosols were carried into the brain through the blood. But studies by others have shown that such small aerosols can also move up the nose and into the brain.

Inflammation underlies many diseases. So seeing it in the brain is not good. Brain inflammation has been linked to dementia in older people. In younger people, Campen says, it’s been linked to neurodevelopmental issues (such as ADHD and autism) and mood disorders (such as anxiety and depression).

Inflammation from smoke aerosols in the brain is “much stronger and more worrisome than what we see in the lungs,” Campen says. However, he adds, it’s not clear at what levels PM2.5 becomes dangerous. “We need to explore this more.”

“Wildfires are perhaps one of the most visible ways that [climate change] is linked to health,” says Stowell at Boston University. And the reality, she says, is that “we’re going to see it remain as bad or worse for a while.”