What’s the fun in fear? Science explores the appeal of scary movies

There are no easy answers about who likes horror or why

October is prime time for watching scary movies with friends. But researchers are still trying to understand why it’s so fun to watch a film designed to freak you out.

miodrag ignjatovic/Getty Images

A woman slides a tape into a VHS player and a black-and-white video flickers on the TV. An eerie hum fills the room as a ring of light glows on-screen. The TV fuzzes over with static for a moment before the image of the ring is replaced by a flurry of other scenes. A burning tree. A writhing mass of maggots. A box full of twitching severed fingers.

The TV cuts to static again. Across the room, a phone rings. Trembling, breathing heavily, the young woman picks it up. “Seven days,” a voice whispers over the line — confirming that the legend of the tape is true. Anyone who watches it is doomed to die exactly one week later.

So begins the 2002 horror film The Ring. For some people, movies like this are too frightening to be fun. But other people relish a good fear-fest. They’ll look forward to visiting haunted houses at Halloween and line up to see the latest scary movie.

Mathias Clasen is one of these people. He became fascinated with scary movies as a teen, he says, “even though I knew that there was a price.” That price might be checking for monsters under the bed. Or sleeping with the lights on.

“But, like for many other people, it’s a price I’m willing to pay,” Clasen says. “I was always curious about that weird fascination — what’s often called the paradox of horror.”

The paradox is this: Horror movies are designed to provoke seemingly bad emotions. Dread. Shock. Fright. Disgust. Yet many people want to sit through films stalked by creepy clowns, blood-thirsty monsters and mad murderers. Why?

Today, Clasen directs the Recreational Fear Lab at Aarhus University in Denmark. There, he and others are shedding light on the appeal of dark media. New research is just starting to untangle who likes horror, and why. The findings may not only help explain a curious quirk of human behavior. They may also reveal how scary media helps people face real-life fears.

The hype about horror

A teen sets off across a cornfield in the dead of night. On the way, he shoulder-checks a scarecrow hung crooked on its post. A few minutes later, he seems to pass the scarecrow again. Confused, the boy walks on. But he soon stops a second time. Here, on the side of the path, stands the scarecrow’s post. And now, the scarecrow is gone.

The question of why people find enjoyment in scenes like this — from Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark (2019) — has no simple answer.

“There are a lot of different reasons,” says Margee Kerr. She’s a sociologist at the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania. The focus of her research is fear. Recreational fear, she says, “does increase all of this activity in our nervous system that — in the absence of a real threat — can be experienced more like excitement and make us feel good.” Plus, “there is that sense of accomplishment” in making it through a real nail-biter of a film.

Clasen’s team also identified this range of motives in a survey of more than 250 American horror fans. People rated how much they agreed with dozens of statements about why they enjoyed the genre. Those responses broadly revealed three types of fans.

The first group were “adrenaline junkies.” They agreed with statements such as “being scared makes me feel alive.” The second group were dubbed “white knucklers.” They reported more negative reactions to scary movies — but sought out those films anyway. They often reported being stressed while watching horror. Some even had nightmares after. The third group of fans were “dark copers.” Those people seemed to use horror to deal with bad feelings and events in real life. They agreed with statements such as “watching horror movies makes me realize that everything in my own life is OK.”

The same researchers also surveyed about 250 visitors to a haunted house in Denmark. There, they found the same three types of horror fans. After the haunt, those fans reported how they felt. They also shared whether they’d learned anything about themselves or felt they had grown as a person by braving the haunt.

Adrenaline junkies felt great. But they didn’t necessarily think they’d learned or had grown. White knucklers were the opposite. “They didn’t really have a mood boost,” says Coltan Scrivner, a behavioral scientist who works with Clasen. “But they were much more likely to report feeling like they had learned something about themselves.” And these fans said they felt they had “developed as a person.” Dark copers both felt great and thought they had learned and grown.

The researchers shared those findings online August 9 in Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, and Applications.

Kerr found similar results among some 260 adults who visited a haunted house in Pittsburgh. Half of the visitors were in a better mood after the haunt. People who said they challenged their fears reported feeling especially good after the haunt. Kerr’s team shared those results a few years ago in the journal Emotion.

Together, the two haunted-house surveys suggest people can revel in both the thrill and the challenge of horror. Kerr also suspects that horror fans would report similar benefits after watching scary movies. But, she adds, future studies will need to confirm that.

Who likes horror?

The door to a young girl’s bedroom swings open. Three haunted-house investigators peer in from the hallway, aghast. A violent whirlwind flings books, music records and other objects around the room. Posters and curtains flap in the torrent. A cackling clown doll whips round and round on a spinning bed. But the little girl is nowhere to be seen. She has already been swallowed up by the evil spirits infesting the house.

Just as there are different types of horror fans, there are those who don’t like the genre at all. Such people never want to watch a scene like this, from the 1982 movie Poltergeist, or a creepy clown, vampire or human-hunting alien. Data from Clasen’s group backs this up. The team surveyed nearly 1,100 American adults. Some of them liked horror. Others really didn’t.

“We didn’t find as clear of a personality profile of the horror fan as I had been expecting,” Clasen says. The differences between horror fans and horror-phobes tended to be small. But the survey did unmask some interesting trends.

People higher in a personality trait called thrill-seeking tended to watch and enjoy horror more. (Thrill seekers often seek out new and intense experiences.) Men also seemed to be slightly bigger horror fans than women. People who said they really liked horror were a few years younger on average than those who really disliked it.

Those findings appeared in 2020 in Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences. And they echo trends seen in past studies. But Scrivner and Kerr caution that these results should be taken with a grain of salt.

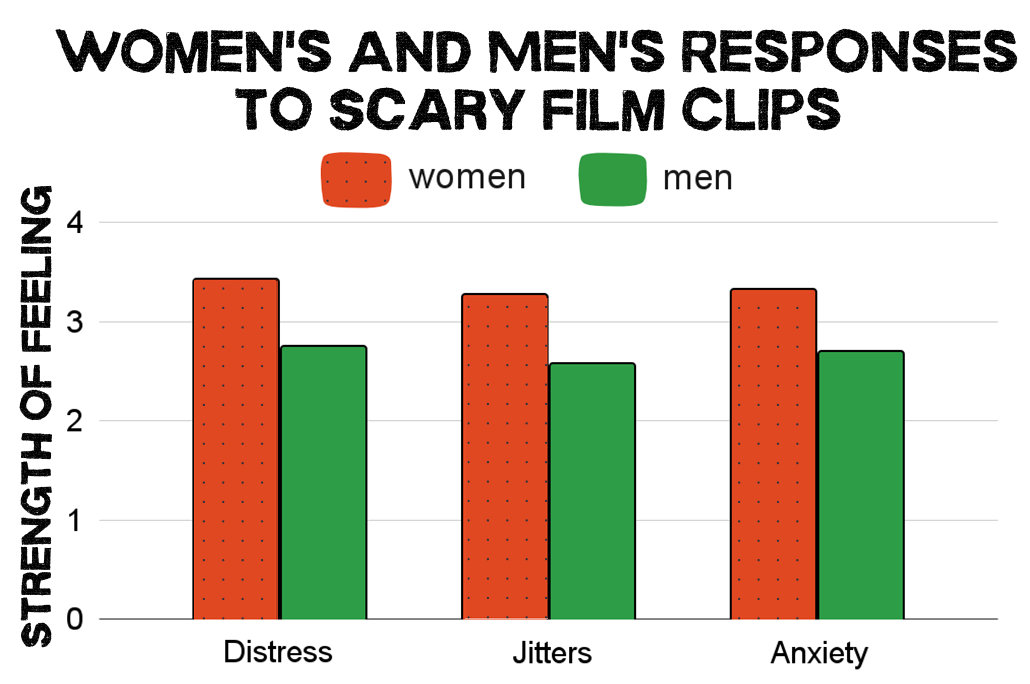

In a study with 41 female and 40 male college students in Italy, researchers showed participants two-minute clips of scary movies. After, participants were asked to rate how strongly they felt different emotions in response to the clips. Women (orange) reported more distress, anxiety and jittery feelings in response to these frightening scenes than men (green) did.

Take the apparent gender divide. In several studies, women have reported that they like horror less than men do and find scary film clips more unpleasant. But does that really mean women are bigger fraidy cats than men? Kerr thinks not. “It comes down to, I think, the way questions are asked,” she says, “and stereotypes.” Men may feel more pressure to appear tough. As a result, they may be less likely to admit in surveys that they are afraid of horror or don’t like it.

Likewise, Scrivner thinks it’s unfair to paint all horror fans as thrill seekers. His research on three types of horror fans shows “that’s true for some people,” he says. “But there’s this huge portion of people that it’s simply not true for.”

A similar trait that may influence how much people like horror is something called need for affect. “Basically, it’s a positive attitude toward emotions in general,” explains Anne Bartsch. “People differ on that — how much emotion they want in their lives.” Thrill seekers want experiences that give them a rush. But people with a higher need for affect seek out experiences that stir up feelings of any kind, good or bad.

Bartsch studies communications at the University of Leipzig in Germany. In a 2010 study, her team looked at people’s need for affect and their reactions to films that evoke negative emotions. The team surveyed cinema-goers in Germany. Fifty-four saw a horror film. Another 65 watched a drama. Before seeing the movies, people answered questions about their need for affect. For instance, those with higher need for affect agreed with statements such as “I need to experience strong emotions regularly.” Those lower in need for affect agreed with statements such as “emotions are dangerous.”

After the movies, people reflected on a scene that had provoked strong emotions. They shared whether those emotions were good or bad and how much they liked having those feelings. People higher in need for affect had more negative emotions, such as fear and disgust. But they also tended to view those feelings more positively than others had. Bartsch’s group shared its findings in Communication Research.

Another decades-old idea about horror fans that may need to be rethought is that people who like this genre must be low in empathy. That is, they must be less affected by seeing others suffer. That conclusion was based mainly on two studies that looked at people’s reactions to scenes of torture or other brutal violence where there was no happy ending. Other studies that measured how much people generally liked horror did not show a link between empathy and enjoyment.

In 2009, Cynthia Hoffner took a closer look at how empathy influences enjoyment of scary films. She’s a media researcher at Georgia State University in Atlanta. Her survey of about 170 young adults found empathy was not related to overall enjoyment of scary movies. But it did seem to affect how people responded to certain aspects of scary movies. Those higher in empathy found it harder to watch characters suffer. But more empathetic people also delighted more in danger and excitement. So, empathy may enhance or impair someone’s enjoyment of horror, depending on the film.

Real-world effects of fictional fright

A young woman smiles serenely as she treads water. She’s enjoying this sunset dip in the sea. But suddenly, she’s jerked downward. The woman’s head disappears beneath the water. When she breaks the surface again, she screams. The young woman tries to paddle away, but it’s no use. Something under the water has her in its grip. And no amount of thrashing will break her free.

A scene like this from the 1975 movie Jaws might give you nightmares. It might even make you nervous about swimming in the ocean. But to those worried about lasting mental-health impacts of scary movies, fear not, says Christopher Ferguson. He’s a psychologist at Stetson University in DeLand, Fla., who studies the effects of media violence.

In the wake of watching a horror movie, you could “be left unsettled, anxious, have nightmares,” he says. But a film that freaks you out is not likely to have a long-term impact on your mental well-being, he says. Watching violent films also does not seem to make people more violent.

Watching horror may actually help some people become more resilient in real life. That’s because horror movies let people practice feeling negative emotions in a safe setting, Scrivner says.

You’re not learning how to escape axe murderers or alien monsters, he says. “What you’re learning is how to deal with feelings of fear.” That way, when it comes to scary situations in real life, “you kind of have this toolkit that you implicitly learned, that you might deploy in order to calm yourself down.”

People may also draw other lessons from horror. For instance, the chaos of a fictional zombie apocalypse may in some ways be similar to the chaos following a real disaster. Watching such chaos unfold on screen may help people do mental dress rehearsals for navigating real crises.

Bartsch at Leipzig and her colleagues found some evidence for this in their interviews with 40 people about what they got out of violent media. “People said that they wanted to be prepared if something happens in their own lives,” Bartsch says. “How they can protect themselves and … deal with it.” Those results appeared in 2016 in the Journal of Communication.

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

Scrivner, Clasen and their colleagues recently found further support in a survey of more than 300 people in the United States. Participants were recruited in April 2020. The researchers asked them how much they were a fan of different TV and movie genres. They also asked about how much distress people had felt during the COVID-19 pandemic and how prepared they were for it.

Horror fans reported lower levels of distress during the pandemic. What’s more, fans of zombie or other apocalypse movies said they were more prepared, such as knowing what to stock up on for a lockdown. These findings appeared last year in Personality and Individual Differences. This is “the most direct evidence that we have so far” that horror helps people brace for real-world threats, Clasen says.

It’s important to note that this study alone is not proof. People who have the emotional endurance to sit through scary movies may just happen to be better at weathering the stress of a pandemic. But Clasen is intrigued by the possibility that horror movies could work like a “fear vaccine” to help someone become more resilient in real life.

Tips for trying out horror

A horde of zombies throws itself against the wall safeguarding a city. The monsters crawl over each other, piling higher and higher against the barrier — until those at the top can fling themselves over the wall. On the ground below, screaming humans scatter. Undead bodies crumple as they land on the street, but the impact only slows them down. Fallen zombies simply wrench their limbs back into place and continue their vicious pursuit of human flesh.

Benefits or not, scary movies aren’t for everyone. And that’s okay.

“To each their own,” Ferguson says. “If you enjoy horror movies … just be understanding that some of your peers are less inclined towards that stuff.”

Kerr agrees. “No one should ever be made to feel bad about themselves for not liking [scary films],” she says. But some self-identified scaredy cats may still be intrigued by horror films and want to try watching one. For them, Kerr has some advice.

“Go into it without any judgment or expectations about what [your] reaction will be,” she says. And if you feel you need to leave, then leave. This can offer someone the opportunity to learn about themselves and their fears.

“Monster movies are good,” she adds, “because you know that they’re not real.” If a scene like the one above from 2013’s World War Z freaks you out, you can remind yourself that a zombie apocalypse is not actually possible.

If you’re not ready to watch a horror movie — even through your fingers with the lights on — there are still other ways to stress-test yourself, Kerr says. One is writing your own horror-movie script. “If you write a story about something that you’re afraid of, you are taking control over it,” she explains. “You’re taking a sense of power in this arena … and that can be really helpful.”