How to turn your hobby into a seriously cool science project

The 2022 Broadcom MASTERS finalists found inspiration in bottle rockets, baseball, blacksmithing and more

For their project, the Simmons twins Sarah (left) and Emma (right) built a device for riders to give a horse asthma medicine without having to dismount.

Courtesy of E. Simmons and S. Simmons

When you picture doing a science project, you might imagine peering through a microscope or building a model volcano. But science can be done anywhere and investigate just about anything. Many teens find inspiration in their hobbies, from playing musical instruments to doing gymnastics. All it takes to transform your favorite pastime into a science project is identifying a problem you want to solve.

And that’s what several finalists in the 2022 Broadcom MASTERS competition did.

This middle-school science competition was created by the Society for Science (which publishes Science News Explores). Each year, 30 finalists compete in teams for prizes and to show off their personal research. Some of this year’s projects were inspired by students’ love for blacksmithing, painting and other hobbies. Science News Explores spoke to six finalists about coming up with ideas, overcoming challenges and tips for science fair success.

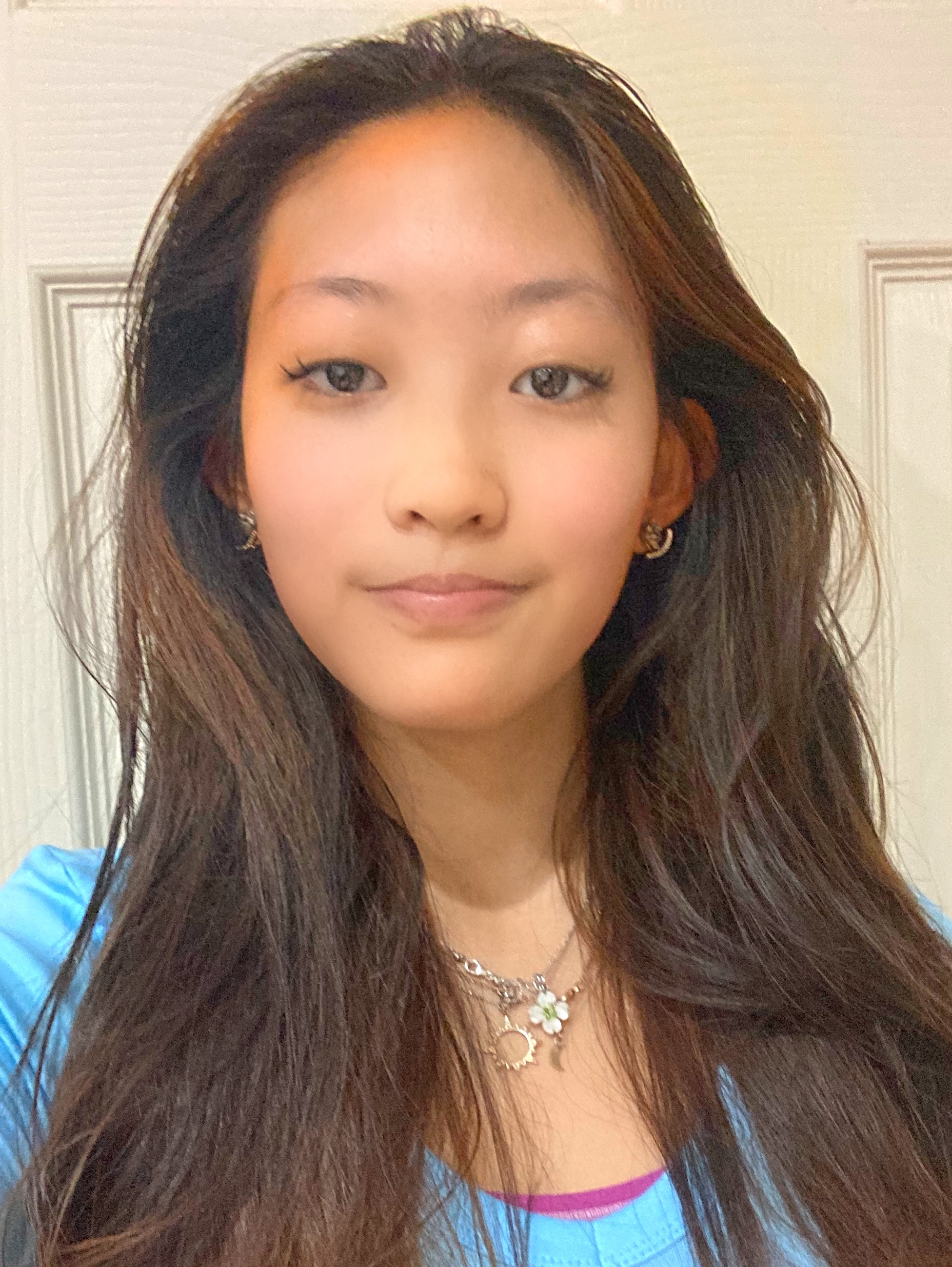

Elizabeth Shen

Elizabeth, 14, designed a new way for computers to store data. Her method is based on the golden ratio. This ratio is often used to create pleasing proportions in artwork. The ratio also appears in nature. The pattern of flower petals follows the golden ratio. The arrangement exposes petals evenly to sunlight. Likewise, Elizabeth’s data storage strategy helps computers write data evenly across memory devices. This could help such devices last longer. Elizabeth is in seventh grade at Davis Drive Middle School in Cary, N.C.

What inspired you to do this project?

“As long as I can remember, I’ve been an artistic person,” Elizabeth says. “In fourth grade, my art teacher taught us about the golden ratio. And at that point it was just, you know, something to use when we were painting.” But last year, Elizabeth had to replace the memory in her own computer. Her dad told her about how computers write data unevenly across memory devices. Elizabeth realized the golden ratio might work in tech, too. “It wasn’t like an ‘ah-ha’ moment,” she says. “It was just… ‘Huh. This might be cool to explore.’”

What was your favorite part of this project?

“Probably the experiments,” Elizabeth says. She tested her golden-ratio technique by running programs on a computer. But before this project, Elizabeth had no coding experience. To prepare, she spent months reading a textbook on how to code. “Writing algorithms is such a tedious process,” she says. “It was just cool to see all of those hours pay off, and see the computer actually just doing stuff that I told it to do.”

Any advice for science fair newbies?

“Don’t limit yourself,” Elizabeth says. “One of the biggest challenges I faced was changing my mindset. I had always thought of myself as a more … writing, artsy person. I never thought that science or computer science would be my kind of thing.” But after learning a bit about programming, “I found that it was actually something I could connect back to what I was familiar with: the arts,” she says. “It was just a new way to express myself. Words, painting, now programming.”

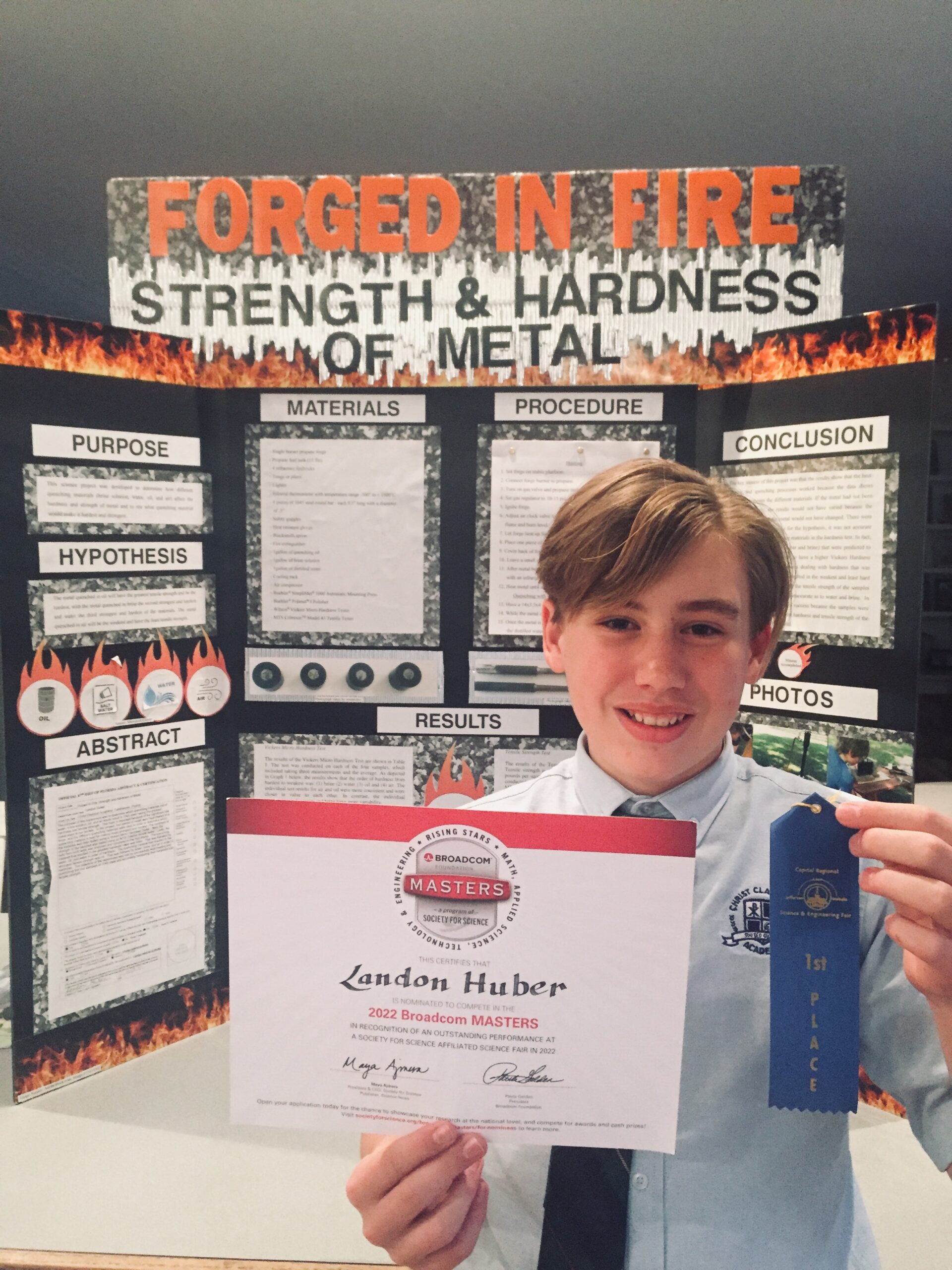

Landon Huber

Landon, 12, investigated techniques for blacksmithing, which involves heating up metal to shape it into different objects. Specifically, Landon wanted to know the effects of different quenching fluids. (Quenching is the process of using a fluid to rapidly cool and harden metal.) Landon heated pieces of steel at home in a forge — a metal box heated by a propane-fueled fire. He then used oil, water, brine (salty water) or air to quench the steel and tested the strength and hardness of each piece. Landon is a sixth grader at Christ Classical Academy in Tallahassee, Fla.

What inspired you to do this project?

“I’ve always liked blacksmithing,” Landon says. That interest was stoked by watching the show Forged in Fire, where blacksmiths compete to make knives, swords and other weapons. On the show, blacksmiths use oil to quench metals. But when Landon and his dad took a blacksmithing class at a local museum, they used water. “The difference made me wonder which one was best,” Landon says.

What was your favorite part of this project?

“It was all pretty fun,” Landon says. “I really liked the forging. But I think my favorite part might have been the experience of going to the college of engineering.” Landon took his quenched metal pieces to Florida A&M University-Florida State University College of Engineering. There, engineers used machines to measure the hardness and strength of a metal. (Hardness is how difficult it is to dent a metal. Strength is how much force is required to break it.) “Because of the experience of going to the engineering college and being able to see all of the stuff that they do,” Landon says, “I’m now more interested in following a career in engineering.”

Will your research results influence your own forging?

“I would probably use oil as my quenching material in the future, because it’s the strongest,” Landon says. “Brine would be the hardest. So, if I needed a hard metal, I would use brine.” Landon is interested in forging knives, as blacksmiths do on Forged in Fire. “I’m a pretty big Lord of the Rings fan,” he adds. “I kind of want to make the one ring to rule them all.”

Emma and Sarah Simmons

Twins Emma and Sarah, 13, have been working together since birth. For their project, they designed a device to give a horse medicine while being ridden. The device uses a hand pump and tubing attached to the horse’s bridle to spray medicine near its nose. Such a portable system could help the roughly one-fifth of U.S. horses that suffer chronic asthma, the teens say. Emma and Sarah are in seventh grade at Mother Seton School. That’s in Emmitsburg, Md.

What inspired you to do this project?

“We have been riding for about four years. And one of the horses that we usually ride has asthma,” Sarah says. “After long rides, especially on hot days, he’ll usually be taking really deep breaths. … To see him struggling to breathe like that is really difficult.”

Adds Emma: “After doing a little bit of research, we saw that there are over 1 million horses in the U.S. that have asthma. And we knew that we had to do something.”

What was your favorite part of this project?

“My favorite part was testing the different components,” Sarah says. “We had to test different sizes of tubing and different types of hand pumps. And I really liked doing that … the problem-solving part of it.”

For Emma, the best part was testing their device. “I enjoyed … getting on the horse and actually seeing that what we created was working, and that this could actually help horses in the future, and the feeling of success.”

What was it like working as a team?

“I’m interested in veterinary medicine, and Sarah’s more interested in engineering,” Emma says. “So, we brought different ideas to the table. And we combined our interests to create an outcome that I think is much better than what we would have come up with if we were working alone.”

What’s next?

“We’re actually starting our next science project right now,” Sarah says. “It’s kind of building off of what we’ve already done. We’re trying to invent something where … we’re able to detect the horse’s respiratory rate. And when the horse has an asthma attack, it will send a signal to an app on someone’s cell phone, which will then alert them when the horse is having an asthma attack.” That could help riders know when to give a horse medicine using the new portable system.

Tate Baum

Tate, 12, wanted to know the physics behind pitching the perfect curveball. For his project, he used a Diamond Kinetics PitchTracker baseball. Sensors in it collect data on how the ball is thrown, such as its speed, spin direction and spin rate. Tate looked at how each factor was related to the strong downward spin characteristic of a curveball. Tate is a sixth grader at Edgemont Elementary in Provo, Utah.

What inspired you to do this project?

“I’m a pitcher on my baseball team, and I wanted to learn how to throw the best curveball,” Tate says. “I’d seen people in the major leagues using this kind of data” to perfect their own pitches.

What was your favorite part of this project?

“My favorite part of the project was probably just actually doing it — throwing all of the balls and collecting the data,” Tate says. One afternoon, he just went outside and threw 34 pitches to create his dataset.

Will your results affect your own pitching?

“It helped me a lot,” he says. Before, “I would just try and throw as hard as I could. But we found out you don’t want to do that,” Tate says. Pitches with more downward spin tended to have lower speeds, higher spin rates and more spin efficiency.

Skye Knox

To most people, a bottle rocket launcher is a way to blow off steam. To Skye, 14, it’s a science project. She turned a bottle rocket launcher into a cloud-seeding device. Cloud seeding sends chemicals into the air that water molecules can glom onto to help form rain or snow. The compound usually used for this can be toxic. So, Skye tried seeding clouds inside a bottle with two other chemicals that have similar crystal structures. Surprisingly, a bottle containing a bit of water formed clouds as thick or thicker without either chemical. Skye is a seventh grader at Pacific Crest Middle School in Bend, Ore.

What inspired you to do this project?

“A lot of my family lives in California,” Skye says. It’s a state that suffers many droughts and wildfires. She wondered: “Is there any way this can be avoided, and how? That’s when I came across this concept of cloud seeding.” This process could help produce more rain in normally dry places.

The two chemicals you tested for cloud seeding didn’t seem to work very well. Why is it important to share negative research results?

“Even though I didn’t get the results I thought I was going to get, it was really interesting to me. It kept me wondering, what will I do next year? What other chemicals [could I try]?” She points out that “even if you don’t get [positive] results, it’s still really cool to see what happens. And it’s even more interesting to think, like, why it didn’t happen. Or, in the future, what can I do to make it happen?” Skye now plans to test cloud seeding at different temperatures and using other chemicals.

Any advice for science fair newbies?

“A lot of people, when they’re first starting their project, they kind of think more about the competition,” Skye says. “How to impress the judges, things like that.” For them, Skye has a Shakespeare quote: “Things won are done; joy’s soul lies in the doing.” Basically, “you’re going to be spending a lot of time on this project. So, really choose something that you’re interested in and passionate about,” she says. “Don’t really worry about the competition side of it. And then you’ll end up having a lot more fun.”

And the winners are…

Elizabeth Shen was among the top winners of this year’s competition. She took home the $10,000 Marconi/Samueli Award for Innovation. This honor recognizes the finalist who “demonstrates both vision and promise as an innovator.”

Skye Knox, Tate Baum, and Emma and Sarah Simmons also won awards at the competition. (Check out the full list here.)

Thomas Aldous took home the top $25,000 Samueli Foundation Prize. This 14-year-old from Pittsburgh, Pa., won the prize not only for his project designing a robotic hand, but also the leadership and collaboration he demonstrated at the competition.

Other $10,000 winners in this year’s competition included:

- Rory Hu, 12, of San Jose, Calif., for discovering that feeding tea polyphenols and caffeine to honeybees may boost their learning and memory.

- Jeanelle Dao, 13, of San Jose, Calif., invented a foot-controlled welcome mat that wirelessly unlocks a door, which could be useful to people with arthritis and other hand problems.

- Mina Fedor, 14, of Berkeley, Calif., found that brain activity is much the same when people are doing active and passive learning tasks.