astronomy: The area of science that deals with celestial objects, space and the physical universe. People who work in this field are called astronomers.

earthquake: A sudden and sometimes violent shaking of the ground, sometimes causing great destruction, as a result of movements within Earth’s crust or of volcanic action.

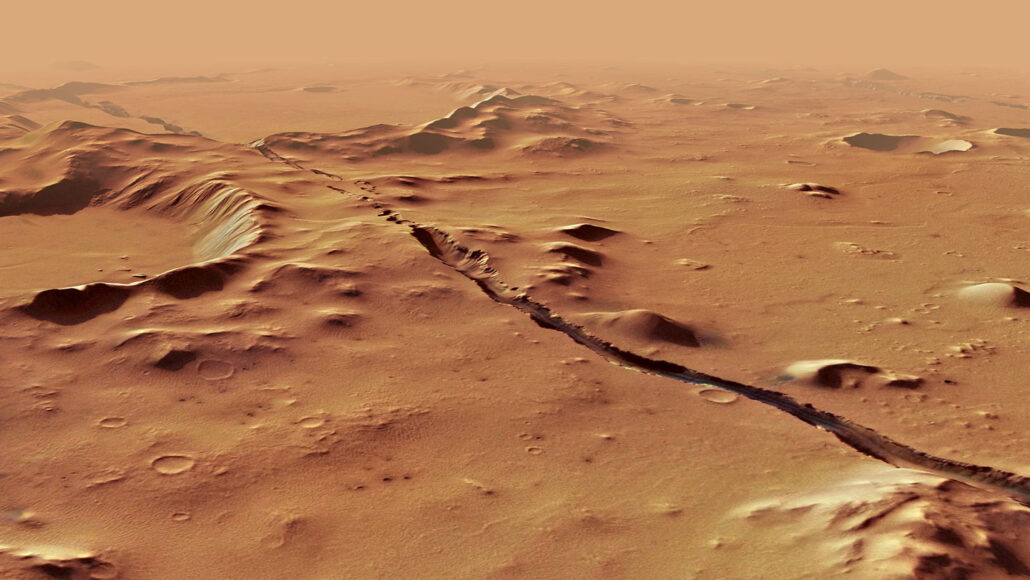

fault: In geology, a fracture along which there is movement of part of Earth’s lithosphere.

geology: The study of Earth’s physical structure and substance, its history and the processes that act on it. People who work in this field are known as geologists. Planetary geology is the science of studying the same things about other planets.

lander: A special, small vehicle designed to ferry humans or scientific equipment between a spacecraft and the celestial body they will explore.

magma: The molten rock that resides under Earth’s crust. When it erupts from a volcano, this material is referred to as lava.

Mars: The fourth planet from the sun, just one planet out from Earth. Like Earth, it has seasons and moisture. But its diameter is only about half as big as Earth’s.

mass: A number that shows how much an object resists speeding up and slowing down — basically a measure of how much matter that object is made from.

moon: The natural satellite of any planet.

Red Planet: A nickname for Mars.

seismic wave: A wave traveling through the ground produced by an earthquake or some other means.

terrain: The land in a particular area and whatever covers it. The term might refer to anything from a smooth, flat and dry landscape to a mountainous region covered with boulders, bogs and forest cover.

wave: A disturbance or variation that travels through space and matter in a regular, oscillating fashion.