Will the internet soon reach the one-third of people without it?

Satellites, lasers and other new tech could soon help connect even truly remote areas

More than a third of the world’s population lacks internet access. Many people who can’t get online live in rural areas or where industrialization has not yet arrived. New tech aims to help such communities connect.

Christoph Burgstedt/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Welcome to Ivujivik (Ih-VOO-yih-vik). No roads lead here. The only way in or out is via an airplane or boat. Thomassie Mangiok calls this northernmost town in Quebec, Canada, home. It’s also where he runs a company. His Pirnoma Technologies Inc. builds apps. It also provides graphic design and IT support. Oh, and Mangiok is a director at Nuvviti (Noo-FIH-tee), the local school, too.

He regularly educates others about technology. “I depend on the internet,” says Mangiok. Unfortunately, internet access in northern Canada’s remote towns often is slow, unreliable and expensive. “It’s hard for us to get what we need up here and to give what we have,” says Mangiok.

He isn’t alone. All around the world — especially in rural areas — people have trouble going online. For some, high-speed internet simply isn’t available where they live. Other people lack devices, training or electricity.

Jane Munga grew up in Nyeri, a rural town in Kenya. She notes that internet service providers cover most parts of Africa. Yet two-thirds of Africans still can’t or don’t use the internet, she says. Around the globe, some 2.9 billion people — or not quite four in every 10 — are not connected. It sets up a so-called digital divide, where some people are connected and others aren’t.

And this is a big problem.

In very remote places like Ivujivik, there may be no local health specialists, banks or sources of world news. High-speed internet is the best way to share these essential services. Other people may need high-speed internet to run a business or get an education.

Back in 2016, the United Nations declared internet access to be a basic human right. “The internet is an equalizer,” says Munga. She now works on technology policy at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington, D.C.

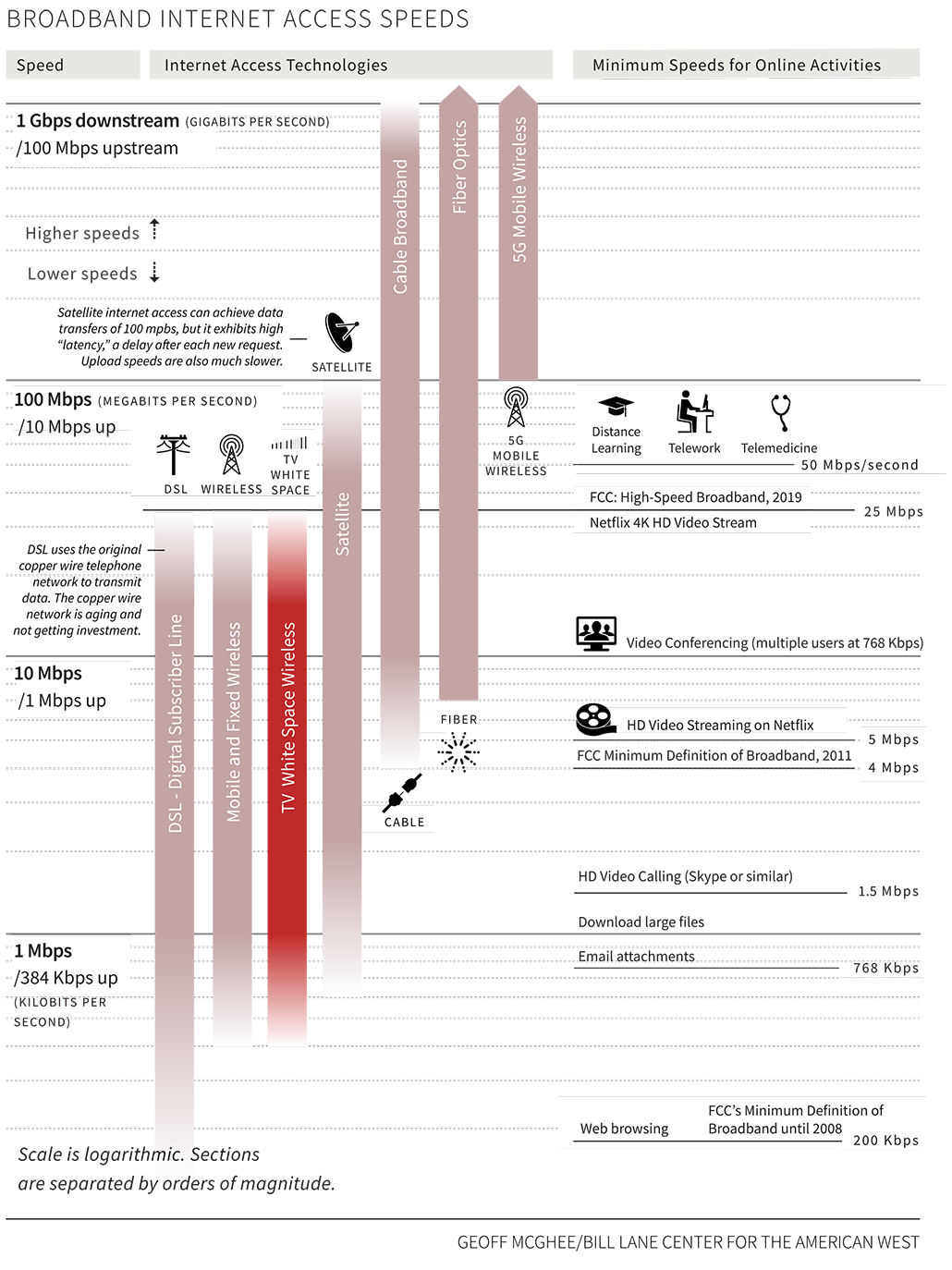

More and more modern technologies and internet services, such as Zoom, only work well with high-speed internet. Although cellular signals can provide such access, they aren’t as reliable as the fiber-optic cables that bring high speeds to much of the world. And those cables still do not reach many rural areas.

But several new technologies are helping to finally connect these places. Lines of low-flying satellites can bounce internet signals between Earth and space to link up remote sites. Unused TV channels can carry internet instead of shows. Lasers can even zap internet through the air.

New tech is crucial to bringing good internet access to those who don’t yet have it. But technology alone won’t fix the digital divide. Education, funding from governments or non-profit groups, and community-led efforts at the local level can help bring the internet to people who lack it. To get everyone online, tech companies and these other groups must all work together.

Cables under ice

Everything on the internet — a text to your friend, a TikTok video, this Science News Explores article — travels from device to device in chunks of data. Those chunks are called packets. And packets need a way to get from here to there. “Think of the internet as kind of like roads or highways,” says Stephen Hampton. He works in Canada at Telesat, a satellite internet company in Ottawa, Ontario.

Someone can travel faster and more smoothly on a highway than on a dirt road. Similarly, packets travel better in some ways than others. Way back when the internet was new, most people connected via landline telephone wires. Think of this as the dirt road of the internet world. Packets travel slowly as electrical signals along these wires. Fiber-optic cables are the internet’s highways. Laid underground or hung from telephone poles, these cables carry packets extremely quickly, as bursts of light.

Of course, highways don’t reach every corner of the globe. Neither do fiber-optic cables. To build a fiber-optic connection to a remote town, workers must dig into the ground or erect poles. Then they lay new cables along the entire distance from a nearby town or city that already has high-speed internet. That can get incredibly costly, especially over very long distances. It’s also tricky when obstacles get in the way — such as mountains, rivers or ice.

Yet high-speed internet is so important that cables are finally reaching out to some remote areas. In 2021, a project began to bring fiber optics to Ivujivik and many other towns in the area. “Boats are going along the coast, laying long lines of cable [underwater],” says Rob McMahon. He studies digital media and technology in Canada at the University of Alberta in Edmonton.

This brand-new, high-speed internet reached Mangiok’s town during the summer of 2022. His kids can now watch Netflix, YouTube and Disney+. These streaming platforms hadn’t worked before. Munga’s hometown of Nyeri, Kenya, got a brand-new fiber-optic connection at around the same time. “I saw them putting up telephone poles,” says Munga. When she worked in Nyeri, she used to use her phone as a hot spot. Now, she can tap into the town’s high-speed internet.

Towers and TV channels

In places that lack a fiber-optic link, people may access the internet only through cellular phone signals. These signals bounce packets to and from cell towers. It’s how cell phones connect to the internet even when there’s no Wi-Fi available. When a cell tower provides the main internet connection for an area, it’s called fixed wireless.

As of 2021, 88 percent of the world’s population lived where 4G or 5G cell coverage was available. These technologies can supply internet speeds comparable to fiber-optic cables. However, the technologies that provide the fastest speeds also span far shorter distances. To carry more data, 4G and 5G use high-energy radio frequencies. Trees, mountains, rain or snow can block these signals and cause delays. So you need to be fairly close to a tower for these connections to work well. In a flat area, signals from a 4G tower can reach around 16 kilometers (10 miles). 5G reaches only about 300 meters (1,000 feet). Fixed wireless is not the ideal solution where people live far apart or in rugged terrain. Since it costs less than fiber-optic cables, though, many places choose fixed wireless anyway.

Another old-school technology might be a better fit for rural areas: television.

TV signals have wide, low-frequency waves. That gives them the advantage of being able to travel farther and through more obstacles than a 4G or 5G cellular signal. The problem with television is that most of its frequencies now carry television shows. Sending internet packets at the same frequency as a TV broadcast would interrupt the show. The key is to find TV channels no one is using. The good news: In rural areas, many TV channels remain unused. These are known as TV white spaces, or TVWS. They fall within the radio part of the electromagnetic spectrum.

One empty channel, however, isn’t enough. Internet providers must find several unused frequencies. Then, they can group them to provide high-speed internet within the TV band of the radio spectrum. Homes or communities need a special receiver to convert a TVWS signal into Wi-Fi or some other form of internet service.

Could there be even better ways to expand access to the internet? Engineers are working on some futuristic approaches. Bring on the satellites and lasers!

Satellites on parade

Before new high-speed cables came to town, Ivujivik’s only connection to the internet was via a geostationary satellite. This type orbits about 36,000 kilometers (22,000 miles) above Earth. At this height, it stays in sync with Earth’s orbit. That means it always remains directly over a single spot on the planet’s surface. It sends packets back and forth as radio signals to satellite dishes on the ground.

But sending packets tens of thousands of kilometers out into space and back takes time — typically around 600 to 800 milliseconds, or around two-thirds of a second. That’s more than 10 times slower than a fiber-optic cable link. The only way to speed up the link, says Hampton, is to “bring satellites closer to Earth.” Satellites in low Earth orbit — or LEO — zip around the planet at heights of 160 to 2,000 kilometers (100 to 1,200 miles). They can now match the connection speed of fiber-optic cables.

These LEO satellites don’t stay put over the same spot on Earth, however. So it takes a parade of them to provide a steady internet connection. The dish or antennas on the ground must follow one satellite until it begins to move out of view. Then the dish must jump to the next satellite without disrupting the link. A satellite dish would have to swivel around to accomplish this jump. Newer, flat antennae are simpler. They can capture signals from any direction without having to physically move, Hampton explains.

LEO satellites have an advantage over geostationary ones. A bad storm may block the signals as it passes between a satellite and its dish. But LEO satellites move relative to the Earth. When multiple satellites are moving overhead, there’s a good chance a storm won’t block them all.

Telesat plans to launch 200 LEO satellites to create a planet-wide network it’s calling Telesat Lightspeed. Other companies, including SpaceX and Amazon, are launching their own LEO networks. Some have already sent thousands of satellites into orbit. (The number needed to cover the whole Earth depends on their distance from the planet.)

How will people access the internet via LEO satellites? In some places, people will have to pay to install a dish or antenna on their home or business. That can be quite costly. Telesat has a different approach. “We’re doing community connectivity,” says Hampton. This works especially well in remote areas.

For this approach, one antenna in a central area talks to the satellite parade. From there, the internet spreads out to the rest of town via cables or a wireless signal. Many remote towns already have some sort of existing network in place. Feeding a new, high-speed connection into such an existing network makes the upgrade cheaper.

From balloons to lasers

If lower orbit helps satellites achieve higher speeds, why not get still closer to Earth? One group tried to provide internet to remote areas with high-flying balloons. They called it Project Loon. Balloon internet proved to be too difficult to make reliable. But the attempt wasn’t all in vain. Along the way, “the team had to figure out how to send data reliably between balloons,” says Mahesh Krishnaswamy. Its solution: a new technology now called wireless optical communications, or WOC.

Krishnaswamy works at a Mountain View, Calif. company owned by Google. It’s known as X, the moonshot factory. He founded and now leads its Project Taara, which is using WOC closer to the ground. This wireless technology zaps packets in beams of laser light. The beams travel between small terminals mounted on a series of poles. Those poles can be up to 20 kilometers (12 miles) apart.

As in fiber optics, beams of light travel extremely quickly through the air. The tricky part is that just about anything can block these signals. Krishnaswamy points to fog, heavy rain, birds — even “a curious monkey” during one test in India. So foggy sites aren’t the best for this tech. But his team has found creative ways to adapt to changes in the environment in real time. In most cases, two terminals can automatically find each other again if they lose their connection.

In 2021, Project Taara used WOC in Africa to beam internet across the Congo River between Congo-Brazzaville and the Democratic Republic of Congo. It’s the deepest river in the world, says Krishnaswamy. It would be too hard and costly to span a fiber-optic cable connection across it. But the distance isn’t that far. Here, WOC is a great solution that can be set up quickly.

“Internet by the people, for the people”

New technologies are exciting, says Munga. “But I have mixed feelings about them.” A new group of satellites or cell tower isn’t a magic solution, she says.

Vickie Robinson in Washington, D.C., agrees. “Just because you build it doesn’t mean they’re going to come,” says this leader of the global Airband Initiative at Microsoft. Airband’s goal is to connect as many people as possible to technology.

It isn’t enough to just make sure internet is available to an area. People have to be able to afford it. Plus, people need the right skills, Wi-Fi routers and devices to get connected. They also need electricity. In many rural parts of Kenya, Munga points out, people lack electricity at home. So when their phone batteries run down, they leave them at a local shopping center to charge all day. (“There’s a small fee for that,” she notes.)

For more than 20 years, Robinson has been working on bridging the digital divide. “It’s my life’s work,” she says. In her current role with Airband, she partners with local companies, governments and community groups around the world. Together, they set up new or improved internet links.

At its heart, the digital divide separates the world unfairly and unevenly. It can limit education. Certain communities are also more likely than others to lack reliable, high-speed internet, says Robinson. Among these are the elderly, people of color, women, girls, people who are part of the disability community and people who lack a secure income. Many projects support these different groups and their efforts to get online.

In one project, Airband is working in Africa with the government of Ghana and an internet provider named Bluetown. They aim to connect 1,000 schools to high-speed internet. The same project is also helping to connect women who run businesses. By selling online, these women can support themselves and their families and also bring more wealth to their communities.

Munga notes that several groups in Kenya are forming community networks for internet access. It is “internet by the people, for the people,” she says. One group called Tunapanda (a Swahili word that means “we are growing”) provides education and training as well as connectivity.

New tech can definitely help expand access. But often the best solutions to connecting some remote area develop when the people in a community lead the way. Mangiok is doing this in Ivujivik. Whenever he shows kids and students his apps, he’s hoping they’ll go out and build their own tech. “I made this, and you can make your own thing,” he tells them.

Creative solutions of all kinds and in all places — from Ivujivik to Nyeri and beyond —are crucial to making sure everyone can access the internet.

NOTE: This story has been updated to note that the Inuit language used in Thomassie Mangiok’s app is Inuktitut, not Inuttitut.