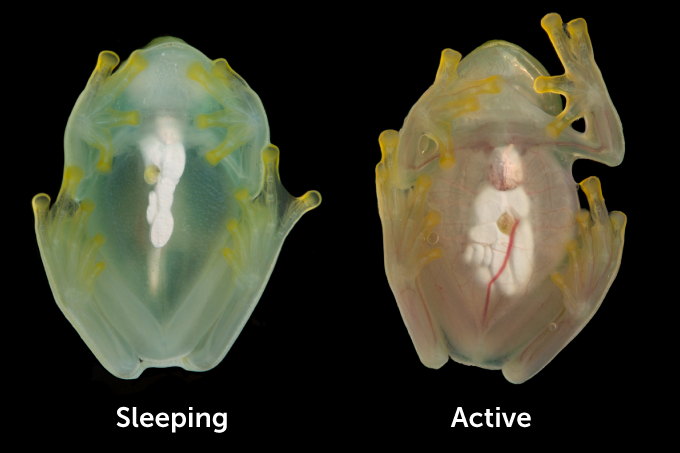

Sleeping glass frogs go into stealth mode by hiding red blood cells

They boost their camouflage by harmlessly storing those cells in their liver

While she sleeps, this female glass frog tucks away most of her red blood cells inside her liver. Her eggs are visible within her transparent ovaries.

Jesse Delia

By Susan Milius

As tiny glass frogs fall asleep for the day, some 90 percent of their red-blood cells can stop circulating throughout their bodies. As the frogs snooze, those bright red cells cram inside the animal’s liver. That organ can mask the cells behind a mirrorlike surface, a new study finds.

Biologists knew that glass frogs have see-through skin. The idea that they hide a colorful part of their blood is new and points to a novel way to improve their camouflage.

“The heart stopped pumping red, which is the normal color of blood,” notes Carlos Taboada. During sleep, he says, it “only pumped a bluish liquid.” Taboada works at Duke University where he studies how life’s chemistry has evolved. He’s part of a team that discovered the glass frogs’ hidden cells.

Jesse Delia is also part of that team. A biologist, he works at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. One reason this newfound blood-hiding trick is especially neat: The frogs can pack almost all their red blood cells together for hours with no clots, Delia notes. Clots can develop when parts of blood stick together in clumps. Clots can kill people. But when a glass frog wakes up, its blood cells just unpack and begin circulating again. There’s no sticking, no deadly clots.

Hiding red-blood cells can double or triple the transparency of glass frogs. They spend their days hiding like little shadows on the undersides of leaves. Their transparency can help camouflage the snack-sized critters. Taboada, Delia and their colleagues shared their new findings in the December 23 Science.

From rivals to research buddies

Delia started wondering about glass frogs’ transparency after a photoshoot. Their green backs are not super see-through. In all his time studying glass frog behavior, Delia had never seen the transparent bellies. “They go to bed, I go to bed. That was my life for years,” he says. Then, Delia wanted some cute pictures of the frogs to help explain his work. He figured the best time to see his subjects sitting still was while they slept.

Letting frogs fall sleep in a glass dish for photos gave Delia a surprising look at their transparent belly skin. “It was really obvious that I couldn’t see any red blood in the circulatory system,” Delia says. “I shot a video of it.”

Delia asked a lab at Duke University for support to investigate this. But he was stunned to discover that another young researcher and rival — Taboada — had asked the same lab for support to study transparency in glass frogs.

Delia wasn’t sure that he and Taboada could work together. But the leader of the Duke lab told the pair they’d bring different skills to the problem. “I think we were hardheaded at first,” Delia says. “Now I consider [Taboada] as close as family.”

Showing how red blood cells act inside living frogs proved tough. A microscope wouldn’t let the researchers see through the liver’s mirrorlike outer tissue. They also couldn’t risk waking the frogs. If they did, the red blood cells would rush out of the liver and into the body again. Even putting the frogs to sleep with anesthesia kept the liver trick from working.

Delia and Taboada solved their problem with photoacoustic (FOH-toh-aah-KOOS-tik) imaging. It’s a technique used mostly by engineers. It reveals hidden interiors when its light strikes various molecules, causing them to subtly vibrate.

Duke’s Junjie Yao is an engineer creating ways to use photoacoustics to see what’s inside living bodies. He joined the glass-frog team, tailoring the imaging technique to the frogs’ livers.

Animal transparency

Despite glass frogs’ name, animal transparency can get much more extreme, says Sarah Friedman. She’s a fish biologist based in Seattle, Wash. There, she works at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center. She was not involved in the frog research. But in June, Friedman tweeted an image of a newly caught blotched snailfish.

This creature’s body was clear enough to show most of Friedman’s hand behind it. And that’s not even the best example. Young tarpon fish and eels, glassfishes and a kind of Asian glass catfish “are almost perfectly transparent,” says Friedman.

These marvels have the advantage of living in water, she says. Exquisite glassiness is easier underwater. There, the visible difference between animals’ bodies and surrounding water is not very sharp. That’s why she finds the glass frogs’ ability to make themselves see-through in open air quite a feat.

Still, having a transparent body is pretty cool, be it on land or at sea.