This biologist uses microwave radiation to save endangered species

Pei-Chih Lee dries reproductive tissues to help vulnerable animal populations

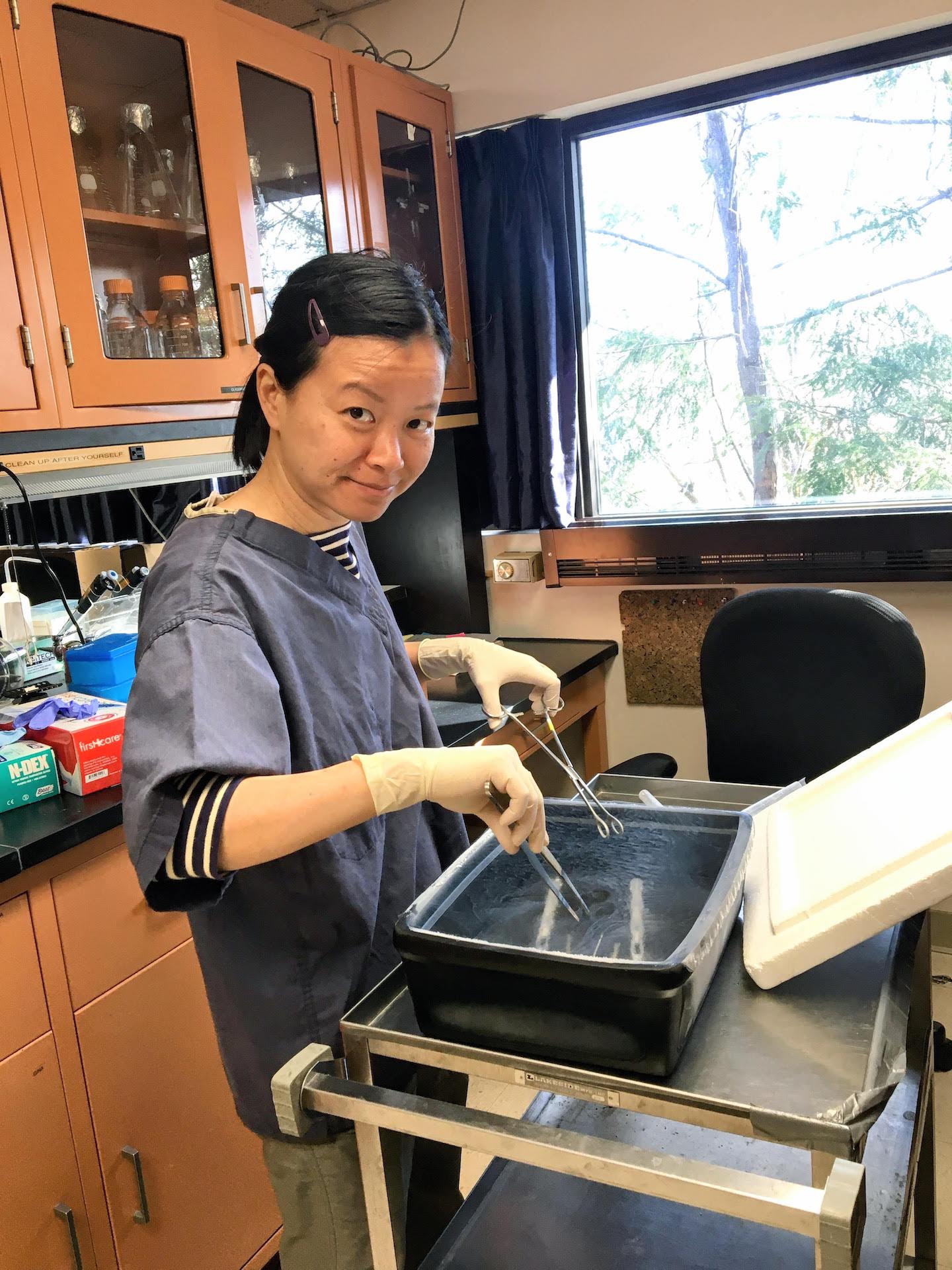

Pei-Chih Lee (here, with her dog Storm) is a research biologist at the Smithsonian's National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute. She collects reproductive cells and tissues for the National Zoo’s genome resource banks.

Courtesy of P.-C. Lee

During March 2020, when many people were hunkered down at home because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Pei-Chih Lee and her colleagues were hard at work at the Smithsonian National Zoo in Washington, D.C. They wanted to ensure that one of the zoo’s giant pandas, Mei Xiang, had her best chance of having a baby that year.

When artificially inseminating a panda, the team usually used fresh sperm — cells collected the same day. But now they needed to minimize in-person contacts. So they turned to frozen sperm, even though they weren’t sure it would work. That summer, though, they found success. Mei Xiang gave birth to a healthy male cub named Xiao Qi Ji, or “Little Miracle.” The cub was the first giant panda born in the United States via artificial insemination with previously frozen sperm.

Helping pandas is just part of the job for Lee, a research biologist at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute. She collects reproductive cells and tissues for the National Zoo’s genome resource banks. These banks preserve genetic material that can help researchers learn more about endangered animals, rebuild populations and breed species in captivity. Lee also has worked to find new methods of preserving these specimens by drying them out with microwave radiation. In this interview, Lee shares her experiences and advice with Science News Explores. (This interview has been edited for content and readability.)

What inspired you to pursue your career?

I’ve always loved animals. As a kid, I would go outside and find all these little creatures in nature. I’d watch Animal Planet channel and all those animal documentaries. So for me, it was very natural to study biology. That part was a no-brainer for me. Then I got into molecular and cellular biology. It’s interesting, because you have all these tools. It’s like solving puzzles. When you’re a scientist, you have all these tools to solve one puzzle. Then you unlock the next one and the next one.

Before I graduated with my Ph.D., I started to think about what I wanted to do next. At that time, I was really open to any possibilities. Then I realized that zoos and aquariums actually do research. I looked more into it. I found out about what they’re doing here at the Smithsonian Zoo with reproductive research on endangered species. The minute I saw it, I knew that this was what I wanted to do. I knew I had the skill set to do it. It also fulfilled my childhood dream of working with wildlife.

How do you get your best ideas?

I enjoy talking to people with different backgrounds and specialties. People have different perspectives. If we’re tackling the same question, it’s always interesting to see what people come up with from their perspectives. It’s also great to go to conferences and learn all about the latest research in different fields. You usually get inspired when you’re in that kind of environment.

What’s one of your biggest successes?

I would say this drying technique that we’ve been developing to preserve reproductive tissues and cells. The technique is inspired by natural organisms that can survive in this dried state for a very long time. A good example is the tardigrade, which can survive super harsh conditions. Or baking yeast, which you buy dried on the shelf in the store. When you put them in water, they will start to propagate. So we are trying to take what scientists have already learned from these different species and try to recreate that in the lab with the cells that we are trying to preserve. It’s not very easy to do. Mammalian cells don’t really have the tools that these organisms have that can help them survive really dry conditions.

We’re mainly focused on using the domestic cat as our model organism right now. We were able to dry cat sperm and store it for over a year. We were then able to inject that sperm into a fresh oocyte (egg) and produce cat embryos from it. We were very excited about that.

What do you like to do in your spare time?

I like going on hikes. I’ll have long walks with my dog, Storm. I also take advantage of being in D.C. I like to go to all the museums and enjoy the art scene here. I love musicals.

What piece of advice do you wish you had been given when you were younger?

I wish I knew this job existed! When I was younger, I had a naive idea that if I wanted to study and save wildlife, I’d have to do the type of research that primatologist and conservationist Jane Goodall does. She’s like a big inspiration for everyone. So that’s the kind of research I was thinking about. Now that I’m here, I’ve learned that the work I do can also contribute to conservation. And there are a lot of different fields like education that are important and a big part of conservation. Nowadays, I just encourage kids to stay open-minded and explore different things. There is more than one path to take you to what you want to do. So just go explore.

What would you recommend someone do if they’re interested in pursuing work in your field?

Give things a try before you decide you don’t like something. Nowadays, all the sciences are so interconnected. For example, I actually collaborate with a lot of engineers as I’m developing these new drying techniques. It doesn’t sound like they would be doing anything with conservation. But through our collaboration, they’re also part of this effort to save species.