This forensic scientist is taking crime science out of the lab

Kelly Knight uses her past struggles and passion for forensics to inspire her students

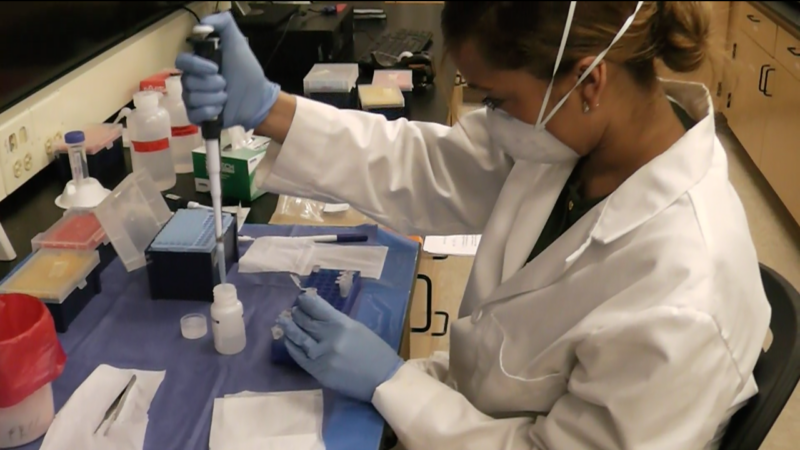

Kelly Knight (here in her laboratory) teaches courses in forensic science at George Mason University. She also teaches the public about this type of science. Some of her best ideas, she says, come from her students.

Courtesy of K. Knight

Like many high school students, Kelly Knight loved science. Still, she wondered if she would ever use things like the periodic table after she graduated. But in her 11th-grade anatomy class there was an activity centered around analyzing blood in a crime-scene scenario. It was the first time Knight saw science put into action. And it introduced her to forensics. “Nowadays, forensics is very popular,” says Knight. “You see it on TV shows. But there was no CSI when I was in high school.”

Knight’s career path wasn’t an easy journey. Imposter syndrome and academic struggles during college made achieving her dream a challenge. Through hard work, however, and a chance mentor who did forensics, Knight found her dream job. She has analyzed samples in a crime lab as a DNA analyst. She has also trained forensic scientists at the forensic sciences division of the Maryland State Police.

Knight now teaches courses in forensic science at George Mason University in Fairfax, Va., where she also is working on a Ph.D. She spends time, too, teaching the public about the science of analyzing crime scenes. Sometimes, this means running a fingerprint activity for elementary students. Other times, she may set up a mock murder case for high schoolers to solve. In this interview, she shares her experiences and advice with Science News Explores. (This interview has been edited for content and readability.)

Q: How did you get to where you are today?

A: Girls being involved in STEM [science, technology, engineering and math] wasn’t encouraged when I was younger the way it is now. STEM was seen as being for boys. You know, “Give the boys the rockets.” Meanwhile, my dad would ask if I wanted to build rockets and launch them. At first, I thought I wanted to be a veterinarian. But in college, I decided to major in chemistry and specialize in forensic chemistry because I remembered how much I enjoyed the blood-typing lab from high school.

After an internship at the Bode Laboratory, a large private DNA laboratory, I decided I wanted to go into forensic DNA. I hit a roadblock, though. There are specific classes you have to take in order to be a forensic biologist. I didn’t have those since I was a chemistry major. So I decided to apply to graduate school. I only applied to one school because I knew being admitted would be a stretch; my GPA was not great. I had really struggled through a lot of my chemistry classes.

But after being waitlisted, I was eventually admitted into the forensic biology program at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond. That’s where I met my mentor, who really changed my life. She saw that I had worked at Bode Lab. I didn’t realize how important that internship would be in helping me change my career path and making me attractive as an applicant. My mentor ended up hiring me and I worked in her research lab.

Q: How do you get your best ideas?

A: I get my best ideas when I’m the most well-rested and in a state where I’ve really cared for myself. That’s when the fog kind of clears away.

Sometimes, when you’re too close to a project or you’ve spent too much time on it, you get this tunnel vision. I can get good ideas once I’ve taken a step away from it — or even in the middle of the night. I used to keep a notepad. Now I just keep my cell phone next to my bed and I open my notes app. At 3 a.m., I may be writing down research ideas.

I also get some of my best ideas from my students. They’re a really huge source of inspiration. I give my students a lot of flexibility in what they study and explore in my classes. I give them lots of opportunities to share that in class. And I’m always surprised by the connections they make.

Q: What’s been one of the biggest successes in your career?

A: One I’m proudest of is the Teaching Excellence Award I won in 2020. And that’s not because of the award itself. It’s because the process to apply for that award was a huge exercise in reflecting on my own teaching practices and the impact I’ve had.

As teachers, we work nonstop. Even as scientists, we start to just rack up all of these accomplishments without reflecting on what we’ve done. There’s not a lot of gratitude in the teaching profession. If anything, it’s the opposite. You feel like you could always do more. And there’s burnout. You sometimes wonder if you’re even having an impact or if you want to teach anymore.

Then I have those moments when I hear from students who say my class really changed their life. As a teacher and a scientist, that has really felt like one of my greatest successes. Impacting students is why I do what I do!

For me, it’s very personal. I had a very challenging time in college. I never felt like I connected with any of my teachers. I always felt very isolated and alone in my struggles. Part of my mission as a teacher has really been to combat that feeling in my students. To try to reach those students who feel discouraged or feel like they don’t belong in STEM. Those who feel like they can’t keep going or feel misunderstood.

I may not understand everything they’re going through, but I want them to know that I care and believe in them. Sometimes it just takes one person to say “I believe in you.”

Q: What’s one of your biggest failures? And how did you get past that?

A: Earning my college degree was the hardest four years of my life. I barely graduated with a 3.0 [B-average GPA]. My grades were really struggling toward the end. That was for a lot of reasons. For example, I was the only Black person in my entire chemistry program; I never had any teacher who looked like me. Because of that, I struggled with feeling like I belonged in chemistry. I often felt isolated.

When I did reach out for help, I felt like I was dismissed. That made me stop reaching out. It was really difficult because I did not have other friends in my major. My other friends had left STEM for many of the same reasons that I wanted to leave. But I was just too stubborn to do it!

Now as a Ph.D. student I still have moments where I experience imposter syndrome. Or if I don’t know what the teachers are talking about, I can be embarrassed to ask. But there are skill sets you can develop to confront those thoughts. Those moments remind me of what some of my students are going through and how I can help them deal with the same things that I’m feeling.

I try to remind myself that just because someone is getting a low grade in a class doesn’t mean they’re not smart or don’t have potential. There could be all sorts of things that could be preventing them from doing well. Even some really smart people struggle through some of their classes.

Q: What do you like to do in your spare time?

A: I like to hang out with my kids and my husband. I have two young boys and they are a lot of fun. I binge Netflix whenever I get the opportunity. I’m always looking for a new series! I like nature, so I try my best to get outside as much as I can. Going to the spa is another one of my favorite things.

Q: What advice do you wish you had been given when you were younger?

A: I wish someone had encouraged me to advocate for myself more and not to be so afraid to reach out for help. I also wish that someone had told me that asking for help is not a sign of weakness.

I come from a line of very strong, independent women — strong to a fault. We get to that point where we feel like we don’t need anyone’s help. But that’s not true. And I feel like if I had kind of been able to push past that a little bit more, I would have been in a better position in some situations.

There are all of these different things within STEM. Some may really interest you — and you may be really good at one. You don’t have to be a doctor or a biologist or a chemist. Do research or look into different STEM programs. These can expose you to a world of possibilities that you didn’t know even existed.