New patch might replace some finger-prick testing of blood sugar

Teen’s color-changing device tests glucose in sweat to signal when insulin is needed

People with type 1 diabetes have to frequently prick their fingers (as seen here) to test their blood-sugar level. Seoyun “Matthew” Lee created a wearable, color-changing patch so that he and others could instead measure their glucose painlessly — in sweat.

Krit of Studio OMG/Moment/Getty Images Plus

DALLAS, Texas — For the last five years, Seoyun “Matthew” Lee has pricked his fingertips at least once a day to test a drop of blood. If the amount of glucose, a simple sugar, is too high, he must get a shot of insulin to lower it. These daily finger pricks are “really lifestyle-hampering and invasive,” Matthew says. So he developed an alternative — a wearable patch. It turns yellow when glucose levels are too high.

The body normally makes insulin to even out blood-sugar levels. But having type 1 diabetes, Matthew cannot make this hormone. That’s important because highly elevated blood sugar can put someone’s life in danger.

Matthew is a rising senior at Daegu International School in South Korea. After seeing younger kids struggle to interpret their blood-sugar levels, Matthew thought a color-changing device might be easier to understand. “As a diabetic,” he explains, “what I recognize is that the precise [blood glucose] number is not really important to us.” Instead, he notes, people with this disease must simply know when throughout the day they will need a shot of insulin.

The body releases chemicals through many routes. The new single-use patch works by detecting glucose in one of them: sweat. Past research shows that you can estimate blood-sugar levels based on how much glucose sweat has.

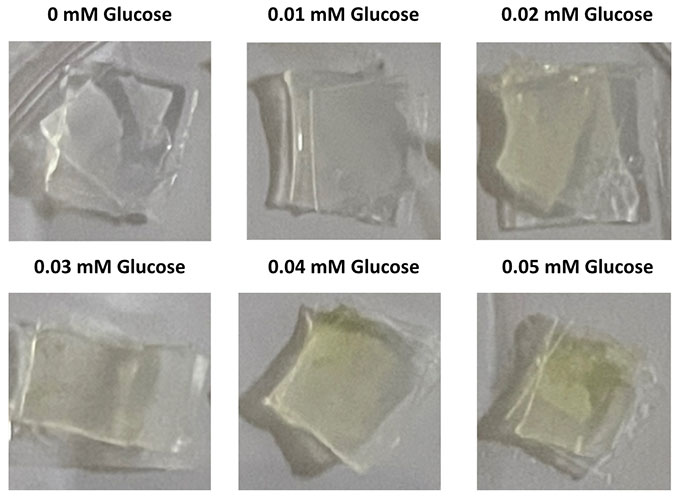

When those levels are normal, Matthew’s patch remains colorless. But when the patch “detects that the sweat glucose is over a certain range,” he reports, “it changes color.”

The 17-year-old showcased his invention here, this week, at the Regeneron International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF). This competition is a program of the Society for Science (which also publishes this magazine).

Hydrogels to the rescue

Two sheets of hydrogel — a jiggly, water-based gel — make up Matthew’s small patch. It’s only 1 centimeter (about 0.4 inch) square. The layer closest to the skin contains a chemical that reacts with glucose. This interaction produces a second chemical called hydrogen peroxide (HY-droh-jen Puh-ROX-eyed). The more sugar there is, the more hydrogen peroxide will be made.

Hydrogen peroxide triggers a reaction in the patch’s upper layer. It causes a protein — called papain (Puh-PANE) — to react with a color-changing chemical. (That papain gets its name from its source — papayas.) The more glucose in sweat, the yellower the patch will become.

Matthew’s patch is painless and easy to understand. And it shouldn’t be very costly. Material costs of his patch are just one-fifth as much as existing glucose-measuring devices. That’s because current gadgets require electrical components. In contrast, Matthew’s patch relies on far less expensive chemicals.

But developing the new patch proved challenging. Sweat contains only a tiny amount of glucose, Matthew points out. So he went through several rounds of testing to perfect the chemical recipe for his patch. “There were times when the reaction didn’t work at all,” he says. “There were times when I had to just go back to the initial step, do things again.” Every time something went wrong, he kept adjusting.

Eventually, all that persistence paid off.

To other students hoping to start a science project, Matthew recommends finding a small problem in your own life that you want to solve. That way, he says, you “have reason and a strong motivation to pursue this, despite the challenges.”

For his work, Matthew won second place — and $2,000 — in the translational medical sciences division at ISEF. He was among more than 1,600 high school finalists from 64 countries, regions and territories. Regeneron ISEF, which will dole out nearly $9 million in prizes this year, has been run by Society for Science since it created this annual event in 1950.

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.