What is my pet saying? Scientists are working to find out

Technology may one day put into words what our furry friends are vocalizing

Pets bring a lot of joy. But it can be very difficult to figure out precisely what a pet wants or needs. Could AI translate what they’re saying?

ISO3000/iStock / Getty Images Plus

Woof! Woof! Your dog stands by a window, barking like wild. You look outside but see nothing. Purrr… Your cat loves cuddles sometimes but runs away at other times.

Wouldn’t it be great, Con Slobodchikoff thought, if technology could help you better understand your pet? A biologist based near Flagstaff, Ariz., he had spent 30 years working to better understand the calls of prairie dogs. Then he switched gears. He now studies the communication of pet dogs.

People have been trying to understand dogs for a very long time. Some focused on dog behavior. Others spent much of their time training different animals. All learned a lot about dogs’ basic body language. Slobodchikoff used that knowledge to counsel people who were having trouble with their pets.

He remembers one case well.

A man reported his dog wanted to bite him. So Slobodchikoff went to the man’s house. He watched as the owner walked over to the dog, towered over the pet and then said, “Good dog!” in a low-pitched, growly voice. “The dog ran into a corner,” Slobodchikoff recalls. The owner had scared the dog.

Slobodchikoff recommended that the man not tower over the dog. He recommended, too, that he say good dog in a high-pitched voice.

The owner took that advice — and ended up developing a great relationship with his pet.

Not everyone has the time to study dog communications or the money to bring in an expert. Slobodchikoff thinks tech could help. He envisions a cell-phone app or device that you could point at a dog. This would capture video and audio of a dog’s behavior and then upload it. An artificial intelligence, or AI, system would later analyze it.

The AI “would translate this for you into English or any other language,” says Slobodchikoff. The result, he explains, may be something like “‘I’m hungry’ or ‘I need to go outside to pee’ or ‘I want to go for a walk.’”

To train the AI system, Slobodchikoff planned to capture data directly from pet dogs. He was in the process of getting ready to begin working with dogs — and then the pandemic hit. To date, he hasn’t yet restarted the project, but hopes to soon.

Search an app store for a pet translator and you’ll find plenty. Some are completely unscientific and silly. MeowTalk, however, is a cat-translation app based on an AI model. In 2021, its creators reported that the AI model achieved 90 percent accuracy at identifying nine different emotional states in meows. These included angry, happy, hunting, pain and rest. The app picks conversational phrases based on these emotions, like “nice to see you,” or “let me rest.”

People who have tried the app say it doesn’t always work well. But better translations of barks and meows may be just around the corner.

Happy rat, nervous rat

New technology might help people understand smaller furry friends.

Kevin Coffey is a neuroscientist at the University of Washington in Seattle. His lab works with rats and mice. These animals make a lot of sounds, mostly in the ultrasonic range. That’s too high for humans to hear. But a special microphone can pick up all their squeaks and squeals. Happy rats tend to make higher-pitched calls. Nervous or annoyed rats chat at a lower pitch. (Mouse calls are less straightforward. But they, too, can be sorted into positive and negative sounds).

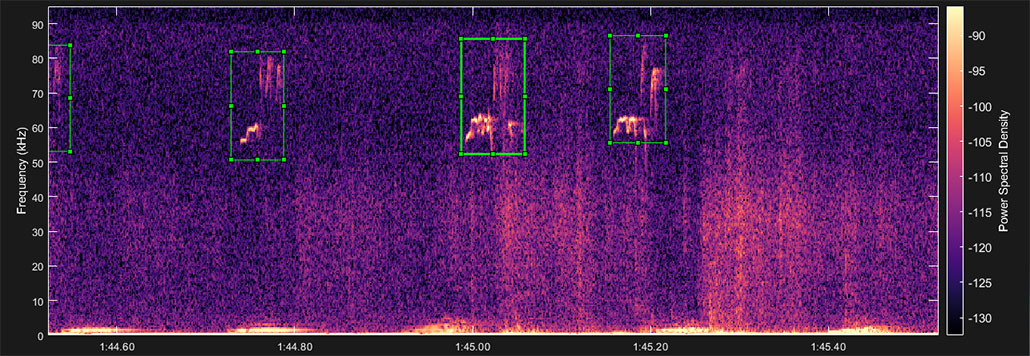

Spectrograms are visual charts that show the features of sound mapped over time. As a student, Coffey had to go through spectrograms of rodent squeaks by hand to figure out how his animals felt. He drew boxes around each squeak. Then he would analyze each sound to try and figure out what the rodents were communicating.

This was very time-consuming. It often took a full 10 hours to go through just one hour of recordings! So Coffey built an AI model he called DeepSqueak.

DeepSqueak

DeepSqueak goes through a visual graph of a sound recording. It draws boxes around each rat or mouse call that it finds. It can also categorize calls to detect emotion. In this case, you’re listening to a happy rat.

To train it, he fed the model many examples of visual graphs of rodent recordings that contained calls. The model learned to pick out and categorize the calls. What once took hours now happens in mere moments.

Coffey’s research doesn’t focus on deciphering the meaning of those calls. But, he says, “It’s probably not just emotion.” He has made DeepSqueak freely available to others. Some have tweaked the model to detect other types of animal sounds. In 2022, marine scientists used the tool to automatically label undersea recordings of the calls of humpback whales, dolphins and fin whales.

Someday, all creatures great and small might have their own translation apps.

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.