A puff of air could deliver vaccines needle-free

This Nerf gun-like device may make injections safer, faster and easier

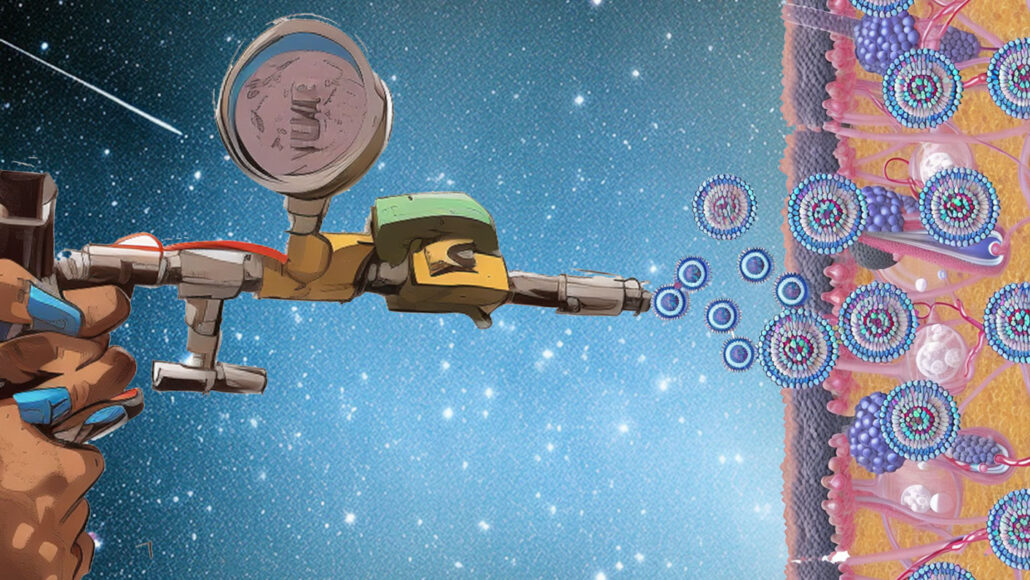

A new gas-based drug-delivery system could deliver vaccines and other medicines. They’d go through the skin, encased in tiny metal capsules that dissolve in the body.

J.J. Gassensmith

Listen to this story:

Have feedback on the audio version of this story? Let us know!

Imagine if getting a shot felt like getting popped with a foam Nerf dart. That could be the case with a new drug-delivery system. It replaces needles with puffs of air.

This innovation could make vaccines faster, easier and cleaner.

“People really don’t seem to like needles,” said Jeremiah Gassensmith in a video describing the work. “That’s really why we invented this thing.”

Gassensmith studies bioengineering at the University of Texas at Dallas. His team’s new tech goes beyond patient comfort, though. The device quickly delivers drugs without touching the bloodstream. And that could reduce the risk of spreading disease. He tested it out on his own arm. It “felt like being shot with a Nerf dart,” he reports. “I could feel it, but it wasn’t painful.”

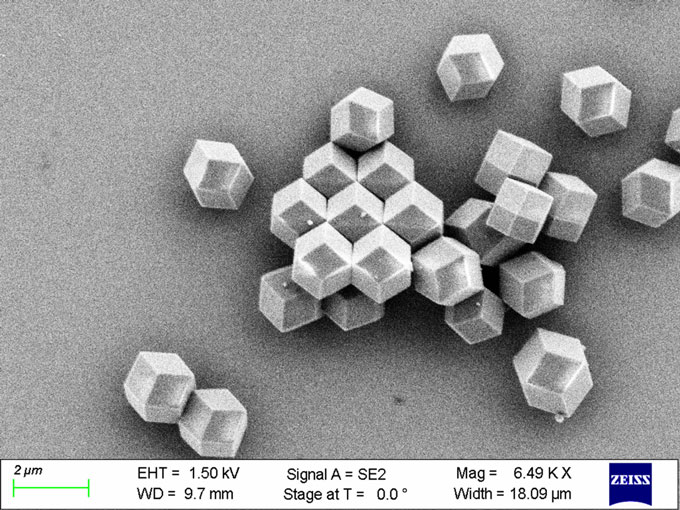

The technology works by blasting a puff of carbon dioxide, or CO2, through the skin. That gas carries a powder made of tiny bits of vaccine wrapped in metallic crystals. The crystal coating is really strong, Gassensmith says. As a result, the vaccine powder does not have to be refrigerated while stored. Once in the body, the CO2 that carries the powder will mix with water.

This creates a weak acid. The acid dissolves the crystal shield. This releases bits of vaccine so that it can now enter the bloodstream.

The new device was inspired by “gene guns” used in agriculture. These shoot DNA directly into crops. Giving a plant those genetic instructions “temporarily tells the plant to do something,” Gassensmith explained in the video. For example, “You can tell a plant to hold off on fruiting if you know a frost is coming.”

Gassensmith decided to build a homemade gene gun for fun. This was early in the COVID-19 pandemic, when he was spending a lot of time at home. In early tests, he shot table salt around his home office. But he soon realized his design could have a more practical use. When he was able to go back into the lab, Gassensmith adapted it into an air-based vaccine system.

His team described its device on March 27 in Indianapolis, Ind. It was at the spring meeting of the American Chemical Society.

An improved design

This isn’t the first gas-based drug-delivery device. It is, however, an upgrade over past systems. For instance, tweaking the gas that carries the vaccine powder can customize how fast the tiny crystal capsules release the drug. Testing showed that the drug released fastest when delivered with carbon dioxide. Plain air, on the other hand, led to a slower, gentler release.

Vaccines work best when released slowly. That allows them longer contact with the immune system. But the team hopes the device could work for other medicines too. And some medicines must be released quickly. One such example is insulin, a crucial drug for many people with diabetes.

The new system is also cheaper than previous designs, which often used gold or other expensive metals to hold drugs, says Yalini Wijesundara. The new setup uses zinc, which is fairly inexpensive. She’s a materials scientist who works with Gassensmith on this project.

To test the injector’s ability to work with vaccines, the researchers used it to deliver proteins into mice. The test proteins were not real vaccines. These stand-ins let the researchers see how medicines delivered by the device would behave inside the body.

To track the proteins inside a mouse, the researchers dyed them red. A vivid red glow under the microscope told the scientists that the proteins had released properly.

The team initially shared its findings late last year in the Royal Society of Chemistry.

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

Not ready to go quite yet

Hurdles remain before this technology could replace needles in doctors’ offices, says Bruce Weniger. A doctor, he teaches at Emory University in Atlanta, Ga. He also studied vaccine technology for 30 years for the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

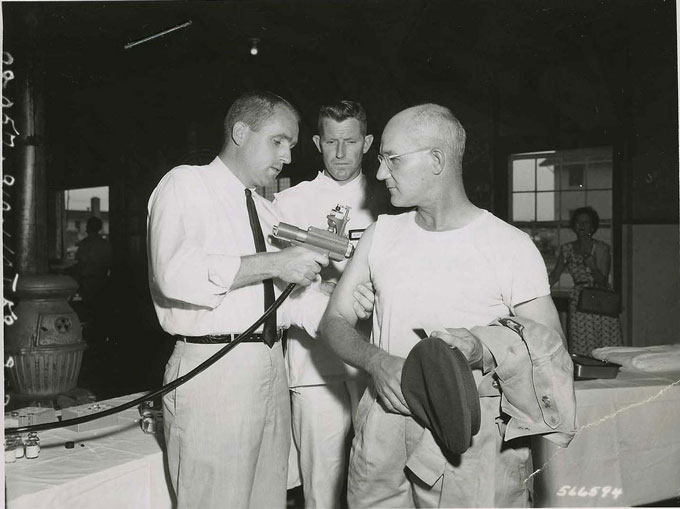

In the 1960s, U.S. doctors tried delivering vaccines using needle-free liquid jets. But problems arose. The liquid could splatter off a patient’s skin. If that person was sick, that splashback could contaminate the tip of the vaccination device with germs and spread disease.

Powdered vaccines could overcome that problem, Wijesundara now says. Solid material is less likely to bounce off the skin.

But more studies are needed to confirm splashback isn’t a concern, Weniger says. He also worries that gas-based vaccines might leave scars. That was a problem with older gas-based systems. Some visible metallic residue remained in the skin.

Future research must also ensure that gas-delivered vaccines build immunity to disease as expected, Weniger says. So far, researchers have only tested that the system delivers medicine inside the body.

This tech might even find use on farms — for livestock vaccines, Gassensmith says. After all, it could beat walking up to a cow with a big needle.

Fear of needles keeps many people from getting vaccinations. Gassensmith is optimistic that this new system might get around that.

This is one in a series presenting news on technology and innovation, made possible with generous support from the Lemelson Foundation.

Correction: This story was updated on November 22, 2023, to attribute some of Gassensmith’s quotes to a video released by the American Chemical Society.