Ultrasound waves can help remove polluting microplastics in water

The waves shift the tiny particles within a flowing fluid for easier separation

Tiny bits of plastic waste, called microplastics, pose problems for drinking water and aquatic habitats. A new technique can remove this pollution using ultrasound waves.

MAXSHOT/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Listen to this story:

Have feedback on the audio version of this story? Let us know!

Wave goodbye to microplastic water pollution.

Ultrasound waves can remove those itty bits of plastic from water. This new treatment could lead to safer drinking water. It also could cut the chance that wildlife will ingest plastic bits.

Tiny pieces of plastic taint water the world over — including drinking water — as well as the air and many foods. As a result, data now suggest all of us have microplastics in our bodies. Scientists don’t yet know all the risks posed by these plastic bits, which are smaller than a sesame seed, or no more than 5 millimeters (0.2 inch) wide.

The ingredients of some plastics can be toxic. And many polluting chemicals will glom onto microplastics. So can viruses and bacteria. Not surprisingly, these plastic bits have been posing risks to wildlife in everything from rivers to the ocean.

Menake Piyasena is a chemist at the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology in Socorro. He worked on the new process with Nelum Perera. She’s a graduate student at New Mexico Tech. In the past, Piyasena used sound waves to separate microbes and other cells from fluids. He recalls thinking: “What if we can use the same method to concentrate microplastics?”

His team’s new system turned to ultrasound — frequencies beyond what people can hear.

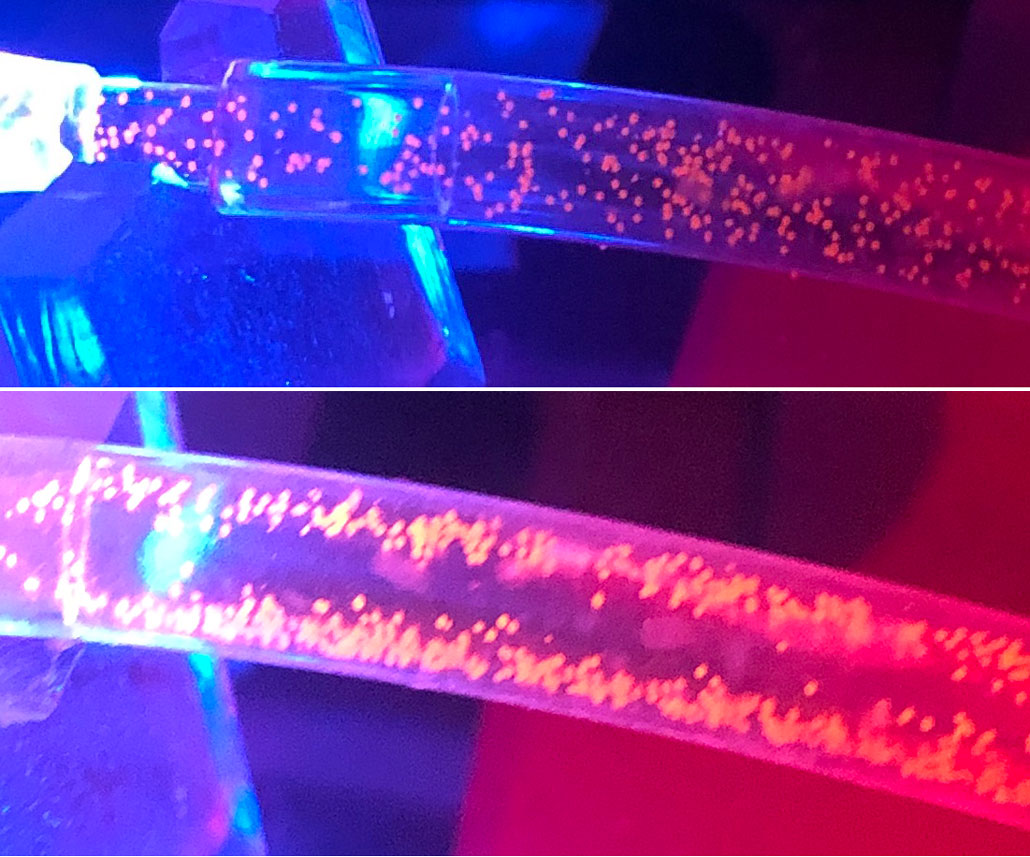

The researchers send contaminated water down a tube. Bits of plastic can be found throughout the liquid. The tube’s water flows past a transducer, a device that converts electrical energy into sound energy. It makes ultrasound waves that travel from one side of the tube to the other, bouncing like an echo through the liquid. When they hit microplastics, these waves exert a force on the particles.

What happens next depends on the size of those plastic bits.

Ones less than about 180 micrometers (less than 7 thousandths of an inch) across will move to the center of the flow. Larger particles — ones close to the ultrasound’s wavelength — will “interact with each other and create an additional force,” Piyasena says. This sends those larger particles toward the edges of the stream of flowing water.

Why size matters when collecting plastic

The New Mexico team is not the only group using ultrasound to remove plastic bits from water. Researchers in Japan have also reported working on this. They used smaller pieces of plastic. Because the New Mexico group used a mix of plastic sizes, it was able to show that the larger bits get drawn to the sides of the water’s flow.

And that was a surprise, Piyasena says.

His team now uses narrow tubing to remove smaller plastic bits from the center of the flowing water. Two additional narrow tubes take out the larger microplastics that flow near the main tube’s walls. The trio of tubes collectively shunt the plastic bits away from the main flow of water, leaving it fairly clean.

Piyasena and Perera added microplastics to water from a pond on campus and from samples pulled from the Rio Grande. Their ultrasound treatment removed about four in every five plastic bits from the water. It took about 90 minutes to clean one liter (1.1 quarts). It cost only about 10 cents to do that. And unlike screens used as filters, this system should not clog and need regular replacement.

“We think our approach will be cost-effective and simple,” Piyasena says. His team unveiled its innovation last year in Separation and Purification Technology. They also shared details about its practicality at the American Chemical Society’s Spring meeting. It was held in Indianapolis this past March.

What’s ahead?

“Microplastics are a problem worldwide,” says research chemist Souhail Al-Abed. He works for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in Cincinnati, Ohio. He’s interested in anything that can get microplastics out of water. In his opinion, this tech is not yet ready to be rolled out for widespread use.

Unlike microplastics in the lab, those out in the environment will pick up contaminants, Al-Abed notes. Water outdoors will also contain other materials, such as microbes, dirt and more. Seawater, for instance, contains salt. The sun’s ultraviolet light can also transform microplastics in ways that may make them behave differently than in the lab.

For now, Piyasena and Perera plan to test water from the ocean and other sources. The team also plans to scale up its process to handle larger quantities of water. “We expect by having multiple tubes bundled together, we can increase the rate of removing microplastics,” Perera says.

“I applaud the folks that are conducting this research,” Al-Abed says. “Research does not have all the answers at day 1 or day 2 or day 100.” But continuing work by these researchers may overcome the current challenges, he says, and prove “a good recipe for the future.”

This is one in a series presenting news on technology and innovation, made possible with generous support from the Lemelson Foundation.