Explainer: Why are so many hurricanes strengthening really fast?

The dangerous trend appears new — and studies have begun linking it our warming world

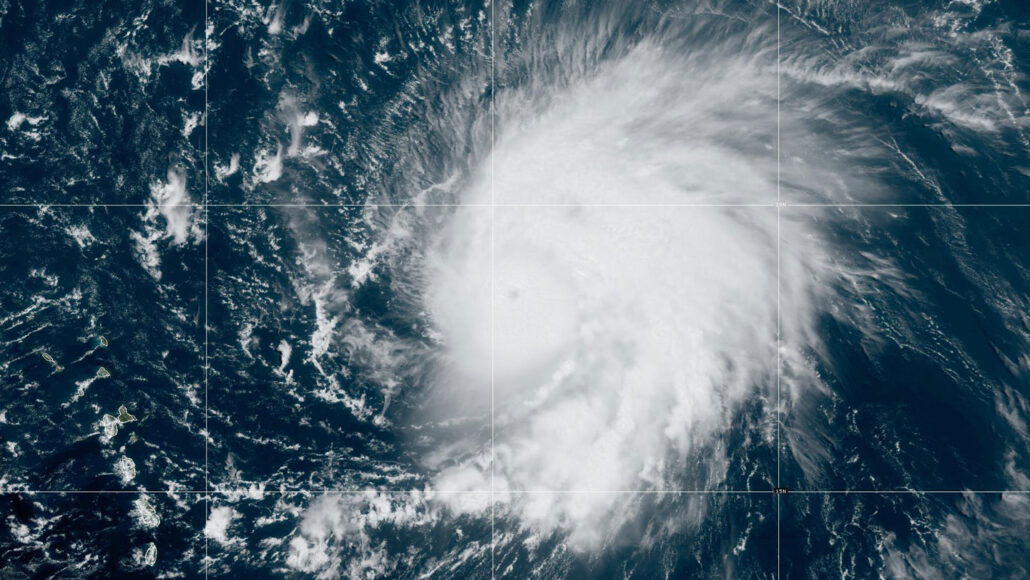

It took Hurricane Lee just 24 hours to explode from a Category 1 to a major Category 5 hurricane (shown here as a Category 5 on September 8).

NOAA/NESDIS/STAR

On the morning of September 5, 2023, a loosely swirling system of thunderstorms formed off the western coast of Africa. One day later, that system had turned into Hurricane Lee. A Category 1 storm, it spun with maximum winds of at least 130 kilometers (80 miles) per hour.

Over the next day, it passed over record-warm waters in the North Atlantic. And they fueled a doubling in its wind speed — to 260 kilometers per hour (160 miles per hour). This storm was now a beast.

In recent years, the world’s oceans have been stockpiling heat as a result of global warming. Now stories of rapidly strengthening tropical cyclones — hurricanes — are becoming fairly common. And not just in the Atlantic.

On September 6, most eyes were focused on Hurricane Lee, notes Eric Blake. He’s a meteorologist at the U.S. National Hurricane Center. It’s in Miami, Fla. But writing on X (what used to be Twitter), he noted that another storm, Hurricane Jova, “is bombing out in the eastern Pacific.” Just a day and a half after organizing into a named storm, it too had exploded — into a Category 4 hurricane.

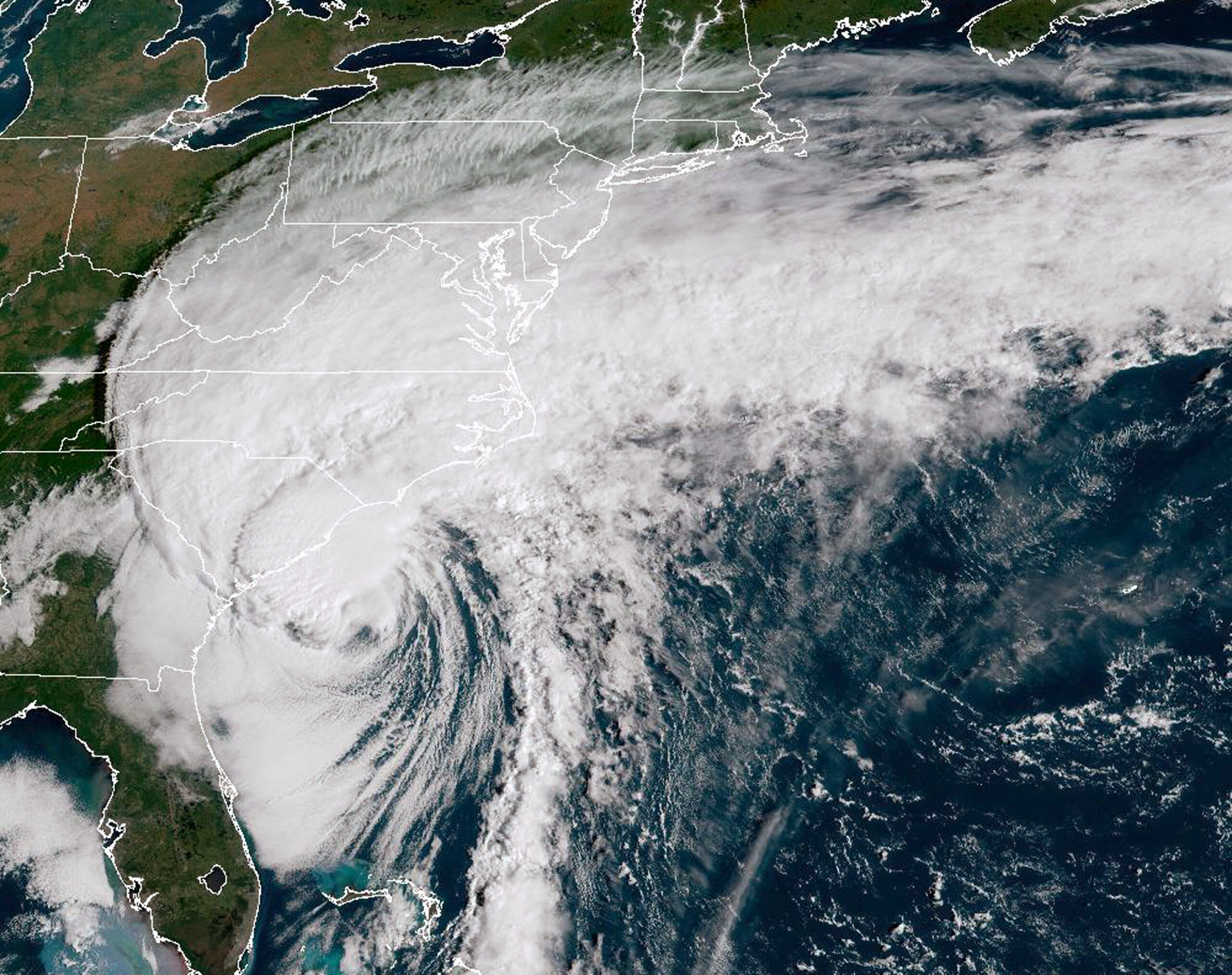

Both storms followed Hurricane Idalia, which slammed into Florida’s Gulf Coast on August 30 packing 120 km/hr to 209 km/hr (or 75 mi/hr to 130 mi/hr) winds. Again, in just 24 hours, it had rapidly built into a monster.

And then there was Otis. In just one day, it morphed from a Pacific tropical storm into a 130 km/hr (80 mi/hr) hurricane. It attained this hurricane status at 2 p.m. on October 24, 2023. Within another 10 hours, it revved up into a 260 km/hr (160 mi/hr) Category 5 beast. It slammed into the west coast of Mexico, leveling much of the resort town of Acapulco and killing more than two dozen people.

Each of these storms easily met — and some greatly exceeded — the National Hurricane Center’s definition for rapid intensification. That’s a jump in a cyclone’s top sustained winds of at least 56 kph (35 mph) within a day or less. Such quickly strengthening storms leave people little time to prepare. That makes these really dangerous.

An October 19 paper in Scientific Reports has now quantified that trend. Andra Garner of Rowan University in Glassboro, N.J., analyzed lifetime wind speeds for every Atlantic cyclone between 1970 and 2020. She divided them into two groups: storms from 1971 to 1990 and storms from 2001 to 2020.

The more recent storms were more than twice as likely to strengthen to a major Category 3 or stronger within 24 hours than the storms in the earlier group, she found. And the likelihood one would intensify from a weak hurricane to a strong one within a day jumped from 3.23 percent to 8.12 percent, she showed. That’s an increase of 40 percent in just a few decades.

Here’s what to know about why such storms are also becoming a trend.

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

Warmer seas and air supercharge storms

Several ingredients are needed to quickly boost a storm’s power. You must start with very warm ocean water and a lot of moist air over it, says Philip Klotzbach. He’s an atmospheric scientist at Colorado State University in Fort Collins. Also very important, he adds: very low vertical wind shear.

That last term refers to winds at different heights that move at very different speeds and in different directions. High wind shear pulls heat and moisture away from a storm’s center. This chips away at its upper structure as the storm tries to form into a tight twirl.

In 2023, Earth’s climate was impacted by the start of an El Niño. It’s an ocean-driven pattern that emerges every few years. An El Niño’s arrival tends to bring more vertical wind shear in the North Atlantic. So El Niño years tend to host fewer Atlantic hurricanes.

But not in 2023.

The El Niño didn’t appear to dampen hurricane formation — or the power of the storms that developed.

The first half of the hurricane season did not see the unfavorable upper-level wind conditions in the western Atlantic that are “typical in an El Niño year,” says Ryan Truchelut. He’s president and chief meteorologist at WeatherTiger. The company is based in Tallahassee, Fla.

This held true even in the Caribbean Sea, he noted. And that’s a surprise, he added, because this is where El Niño’s shearing power tends to be strongest.

Generally, El Niño years bring more of a contrast in temps between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The eastern tropical Pacific tends to heat up while the Atlantic stays relatively cool. But 2023 saw record-breaking ocean temperatures in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Gulf of Mexico. The El Niño warmed Pacific waters about 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) above normal. Parts of the Atlantic warmed more — up to 3 degrees C (5.4 degrees F) above normal.

Contrasting temperatures between the oceans drive jets, Truchelut says. Jets are fast air currents moving high in the atmosphere. A 2023 “lack of this contrast is likely responsible for the missing [wind] shear,” he concludes.

Feverish temps in the Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico can set the stage, says John Kaplan. Then all that’s needed to whip up monster storms is a span of time with favorable wind conditions, he says. Kaplan is a hurricane modeler, based in Miami. He works for the Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, a federal facility.

For rapid hurricane strengthening, he says, those favorable conditions are enough. “If there’s a window — even if not a very long one — the [weather] system can take advantage of it.” In 2023, he notes, that was the case for both Hurricanes Lee and Idalia.

More storms are rapidly intensifying

It certainly feels like most recent hurricanes have strengthened very rapidly. But is that true? And if so, was it due to climate change? In fact, that trend indeed appears real.

In August 2023, researchers reported that over the last 40 years, the yearly number of tropical storms around the globe that rapidly intensified just offshore — within 400 kilometers (250 miles) of land — has grown steadily. It had been fewer than five per year in the 1980s. By 2020, it was some 15 per year.

Open-ocean storms showed no similar increase.

A 2021 study reported that since 1982, hurricanes have been migrating closer to the coasts. And those closer to shore pose the biggest threat to people.

In 2019, another team focused on records of changes in hurricane wind speeds over spans of 24 hours. From 1982 to 2009, there was a tripling in the number of storms that underwent a rapid strengthening, these showed. And using computers to model climate, the researchers were able to strongly link this trend to human-caused climate change.

Truchelut notes that the same team also authored a study last year. It further supported that trend. Over the last few decades, it found, a larger share of hurricanes underwent a really rapid boost in strength at some point.

Klotzbach at Colorado State and his colleagues have found another fingerprint of climate change in rapid hurricane strengthening. It’s an increase in global sea-surface temperatures over the last 30 years. This rise correlates well with how strong hurricane winds are capable of becoming around the world. The team reported its finding last year.

That observed increase was particularly apparent for the most monstrous storms — those whose wind speeds increased by a whopping 93 kph (57 mph) in just one day.