Black holes and activism inspire this astrophysicist

Mallory Molina looks for new ways to find elusive black holes

“There’s often a stereotypical path that people are recommended to take,” notes astrophysicist Mallory Molina. “You don’t always have to take that path.”

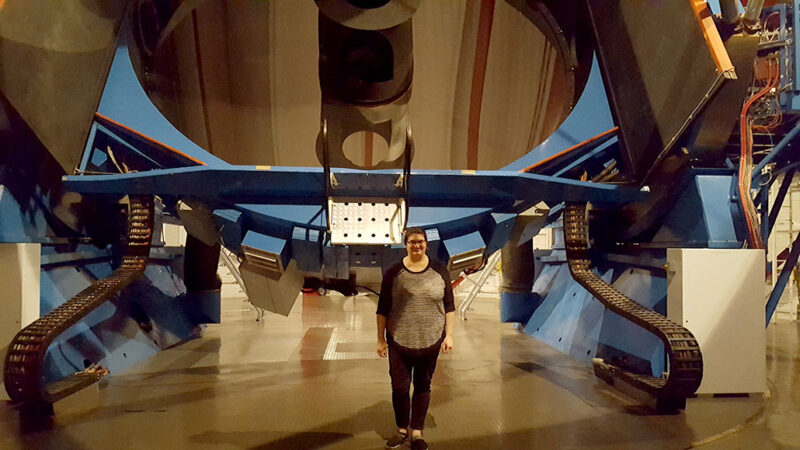

M. Molina

As a young child, Mallory Molina visited the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas, with their parents. It’s where NASA trains astronauts. Molina left inspired, wanting to study space. Their parents, though, had some concerns. “They were afraid it wouldn’t work out,” says Molina. “They suggested I switch career paths, but I never did.” Now, Molina is an astrophysicist studying black holes.

In 2021, their team at Montana State University in Bozeman discovered a new way of finding supermassive black holes tucked away in dwarf galaxies. The red glow from these black holes — which can be hundreds of thousands of times bigger than our sun — can tip off researchers that a black hole is actively feeding. Now at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City and Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn., Molina continues to investigate how these black holes interact with their host galaxies. These dwarf galaxies can help us better understand how black holes formed in the early universe, they say.

Molina’s path to the stars wasn’t always easy. And their struggles as a Mexican-American student inspired them to find a way to help others. They are one of the cofounders of Towards a More Inclusive Astronomy (TaMIA). The organization helps universities set up discussion groups where students can talk about how to make astronomy programs more welcoming to everyone. The program allows students who experience the world differently to feel heard in their astronomy departments, says Molina. In this interview, Molina shares their experiences and advice with Science News Explores. (This interview has been edited for content and readability.)

Q: What inspired you to pursue your career?

When I was little, I was amazed by all the things that we didn’t understand about space and the universe. There are so many objects that you can’t see on Earth. I remember being in awe of these giant planets millions of miles away from us. I knew nothing about them, but there was so much waiting for me to learn about and explore. All the different possibilities felt super exciting to me. As I got older, I fell in love with physics. I realized that you can combine space and physics together. And that really got me excited for college.

I got a full scholarship to Ohio State University. We couldn’t turn that down. I ended up getting an opportunity to do some research on black holes. And I randomly picked to work on black holes because they sounded cool. That experience ended up really sparking my interest in astrophysics.

Q: How do you get your best ideas?

A lot of my ideas are built on previous observational work. For example, I’ll look at the spectrum of gas around a black hole. I’ll see interesting things, and it’ll inspire me to look for something new. What I’m most well-known for right now is coronal lines from black holes. Those are high-energy X-rays emitted by black holes as they suck in matter. Normally, they’re found with big black holes, and even then, not all the time. I ended up observing them in small black holes.

Having good collaborators and good discussions also leads to great ideas. That’s something that’s really important in astronomy that people don’t think about. There’s this idea that you have to be a lone scientist who comes up with all of your ideas by yourself. That’s not really how astronomy works anymore. You may have a starting idea, but it’s always going to be improved by other people. They’ll think of something you didn’t. I often kind of bounce ideas off collaborators that I trust. This helps flesh out a better idea for a project.

Take my paper with Amy Reines, the astrophysicist I worked with at Montana State. I was following up on some of her work on black holes detected through radio waves. I found the coronal lines, and I thought it would be a good idea to search for more. But in talking, we came up with a more detailed project.

Q: What was one of your biggest failures and how did you get past that?

I feel that scientific failures aren’t necessarily that big of a deal. Someone may discover something new that impacts one of your previous papers. It may end up showing you were wrong in a paper. At that time, though, you were right and trying your best. Now we just know different things about that topic.

The lowest point in my career was in grad school. I was not doing as well as I had done in undergrad, and everybody else seemed to be so much farther ahead when it came to grades and research. I felt isolated and was thinking of quitting. I was told by some people that I only had my spot because I was Mexican-American, that I didn’t even count as a Mexican-American. I was told that it wasn’t fair to white people that I took their spot. Since I wasn’t doing that well in school, I believed them. I actually had made up my mind to quit astronomy forever.

I talked to my advisor about it. He was really helpful in encouraging me. He said I had some improvements to make, but that I wasn’t doing as bad as I thought I was. He helped me find ways to create inclusive environments, which is a very big thing for me. I ended up cofounding TaMIA.

I realized that being a scientist is more than just doing science. It’s about making science welcoming for everyone and welcoming for myself. It’s about letting me be myself instead of trying to fit this mold of what I thought a scientist was. I was able to push past that and ended up really excelling in my career.

Q: What do you like to do in your free time?

I go hiking with my two dogs a lot. I also enjoy movies, reading and video games. My husband cooks, but I sometimes like to bake. Now that I’ve got a one-year-old, a lot of my life is listening to Disney songs on repeat and focusing on her.

Q: What piece of advice do you wish you’d been given when you were younger?

My parents told me it’s important to be true to yourself no matter what field you enter. That’s how you’re going to be successful and happy in it. I think that was the hardest thing for me to learn.

Physics and science overall tend to be done in certain ways. Sometimes, this is necessary. You need to follow the scientific method, reduce the data correctly and use certain tools to analyze it. But there’s often a stereotypical path that people are recommended to take. You don’t always have to take that path, though, or be exactly like everybody else to be successful. You can kind of create your own adventure, in a way.

I shaped my own career by creating more inclusive environments and trying to support other people. And that became such an important part of who I am as a scientist. Allowing yourself to be yourself and not feel like you have to fit into a specific box is something that I wish I had learned a lot younger. Even when you’re a kid, you just want to be like everybody else. It’s okay to be yourself, though.