Bottled water hosts many thousands of nano-sized plastic bits

The finding comes from tests of a new tool to ID smaller-than-ever plastics in water

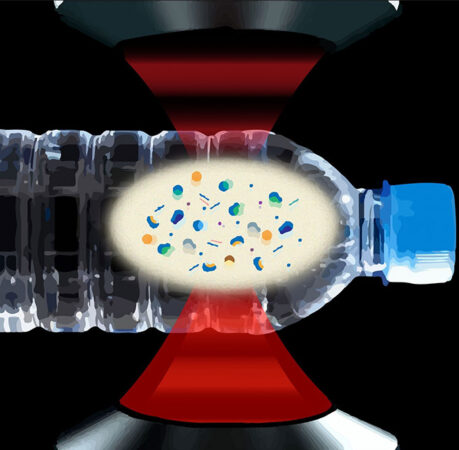

Scientists found hundreds of thousands of nanoplastics in bottled water and identified seven types of plastics in the mix. This is 10 times more than what had turned up in previous studies.

Henrik Sorensen/ DigitalVision/Getty Images

By Laura Allen

Tiny plastic bits are everywhere — wafting in the air, riding ocean currents, raining down on plants and swirling in bottled water. The smallest of these — nanoplastics — have been hard for scientists to study. Now, researchers have developed a new method to identify these super-tiny bits, each billionths of a meter in size. And when used on bottled water, the method turned up more plastic than ever before.

Beizhan Yan is an environmental-exposure scientist at Columbia University, in Palisades, N.Y. He had studied microplastics — tiny pieces that range from 1 to 5 millimeters across. Yan wanted to study the even smaller pieces that form when these microplastics break down. Unfortunately, he lacked the tools to do it.

These nanoplastics are less than 100 nanometers wide, Yan notes. “About the size of a virus.”

Yan teamed up with Wei Min, a physical chemist, also at Columbia. Their team developed a new method. To do it, they used what’s known as stimulated Raman scattering microscopy.

“We’re using really powerful lasers,” explains Min. These probed the chemical makeup of particles in bottled water, looking for plastics. Different plastics “have different chemical bonds. And each will vibrate at a different energy,” Min explains. His team’s laser is tuned to identify the plastics based on these vibrations.

Electronics measure the interactions between the laser and the particles. The team then created a machine-learning algorithm. It could identify seven types of common plastics from the vibrational data. The tool also can map where the plastics are in the water.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

Swimming in plastics

The researchers found hundreds of thousands of plastic particles per liter (quart) of water. They found plastic in all three brands of bottled water they tested. This amount is 10 to 100 times more than had turned up in studies that had focused on microplastics.

“It’s because most of the particles [90 percent] we found were in the nano size,” says Naixin Qian. She’s a graduate student and physical chemist on the Columbia team. The conventional ways to find microplastics just weren’t able to detect these smaller bits, she says.

The new tool identified tiny bits of PET plastic. It’s the same plastic used to make the bottles. The tool also found polystyrene, PVC and polymethyl methacrylate. The team suspects that filters at the bottling plant were the sources of these. But most of the nano bits found were not one of the seven plastics their tool could identify. The researchers don’t know what they are or where they came from.

Yan’s team shared its results online January 16 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Some scientists are skeptical

Not all scientists are convinced by the new numbers. Among them is Dušan Materić. He’s an analytical scientist. He heads a research group that studies micro- and nanoplastics at the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research. It’s in Leipzig, Germany.

Materić is working to create standard methods to test for nanoplastics. They don’t exist yet, he says. Such new methods will have to be scientifically sound. Without that, there’s no way to truly know how many particles are there. What’s more, he adds, it’s easy to contaminate samples. When this happens there’s no telling where the polluting bits might have come from. Were they already in the water? Did they come from a researcher’s lab?

Machine learning is a type of artificial intelligence. Using it to identify the plastic bits, as the Columbia team did, can be another source of error, Materić says. The new algorithm may be prone to “false positives,” he says — where other things are mistaken for plastic. This would exaggerate how many plastic bits were present.

More standardization is needed here, agrees Kurunthachalam Kannan. He’s an environmental chemist who has studied microplastics. He works at New York State’s Department of Health in Albany. Without a standardized way to test for micro- or nanoplastics, results from different labs can’t be compared in terms of their number or size, he points out.

But whether the water holds 10 pieces of nanoplastics or 100,000, one thing is certain — they’re there. And one big question remains: What are their health impacts?

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

Nanoplastics can enter the blood

These nano-scale bits are very, very small, notes Phoebe Stapleton. She’s a toxicologist at Rutgers University in Piscataway, N.J. She also is part of the team that measured them in water. Bits this size can be breathed in. From the lungs they could pass into the blood. Or, if consumed, they could pass into the blood from the gut, says Stapleton.

Once in the blood, the tiny bits can move throughout the body, reaching cells anywhere.

Rain can wash nanoplastics from the air and onto plants, including farm crops. Scientists found some plants absorb these tiny plastics. In fact, eating leafy plants is yet another pathway for these tiny plastics to enter the body. It’s something two researchers at the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing described. They mentioned this in a January 3 commentary in Environmental Science & Technology Letters.

But are these nano bits harmful? Past studies placed nanoplastic bits directly onto cells to study their impacts. That caused some toxicity and cancer-causing changes, Stapleton notes. But scientists don’t yet know what happens when the exposure is to the whole body.

“We know they get in,” says Stapleton. “So really, the question is about that toxicity” — what harm they might cause to us. She plans to investigate that.

Keep drinking clean water

Most of our exposure to nanoplastics probably comes from the air, says Materić. For those worried about water quality, he recommends using an activated-charcoal water filter.

“Dehydration probably causes more [health risks] than exposure to nanoplastics,” adds Yan. So don’t hesitate to drink bottled water if that’s all you have. However, past studies have shown tap water contains fewer plastic bits than bottled water.

“The fact that we’re exposed to so many plastic particles from different sources is the reality we have right now,” notes Qian. But we can limit this pollution by reducing, reusing and recycling plastics. We can also look for using alternatives to plastics.