Did James Webb telescope images ‘break’ the universe?

Astronomers are still figuring out how to interpret what this space telescope is telling them

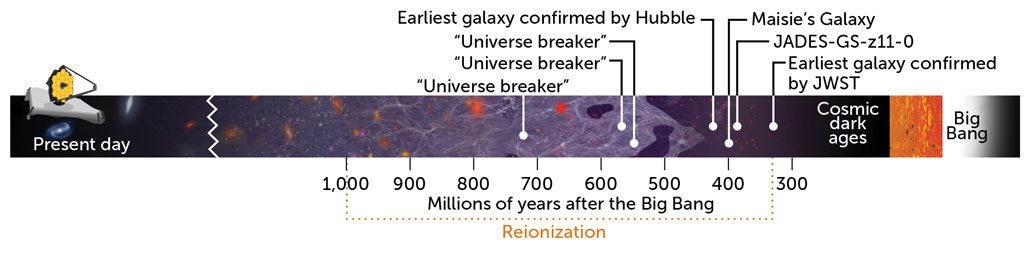

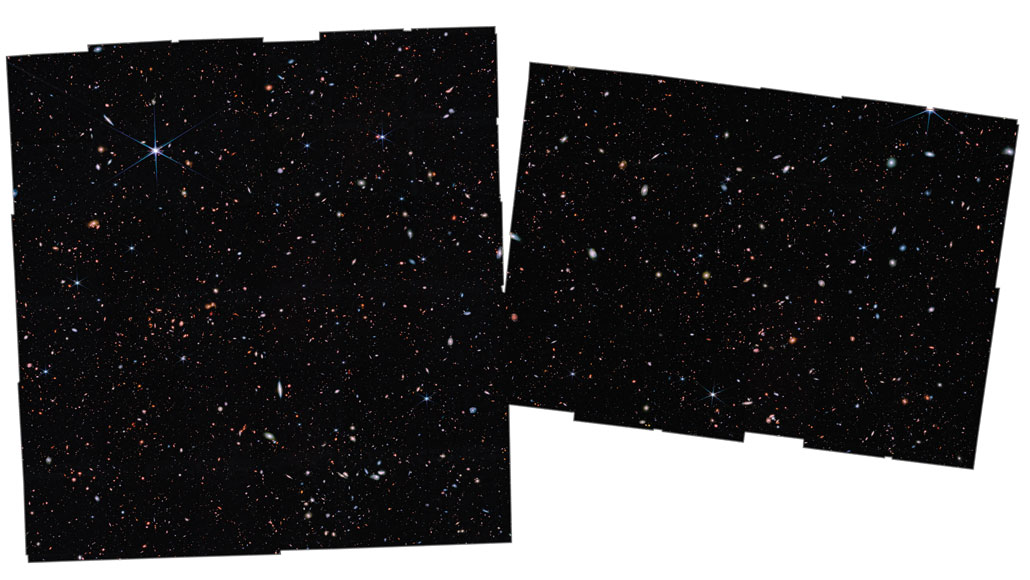

One of JWST’s first images of the universe (pictured) swarms with galaxies. These included several objects that at first appeared to be too big and bright to be explained with current physics.

NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope is raising big questions about the early universe.

In its first images, JWST captured what appeared to be huge galaxies in the ancient universe. In fact, those galaxies looked much too big to fit scientists’ current theory of how the universe grew up. This has raised some concerns that the history of the early universe needs to be rewritten.

But a new look at old data from the Hubble Space Telescope tells another story. Perhaps JWST hasn’t upended cosmology as much as some scientists feared. Instead, the huge-looking galaxies JWST saw may have simpler explanations.

Researchers shared these findings in the February 9 Physical Review Letters.

JWST is giving us a new language to understand the early universe, says Julian Muñoz. He’s a cosmologist at the University of Texas at Austin. “Before we say, ‘Hey, we need to throw away everything we knew in cosmology,’ we should understand this language.”

‘Universe breakers’

The trouble began almost as soon as JWST first peered into the distant universe.

When this telescope looks at distant objects, it sees those objects as they appeared far back in time. Why? Because the light from such far-off objects has taken so long to travel to Earth. So when JWST peers at the most distant cosmos, it sees things as they were shortly after the Big Bang.

JWST’s first views of such distant, ancient regions of space were confusing in two ways.

First, some of its images contained huge numbers of galaxies. Far more, in fact, than astronomers thought possible so far back in time.

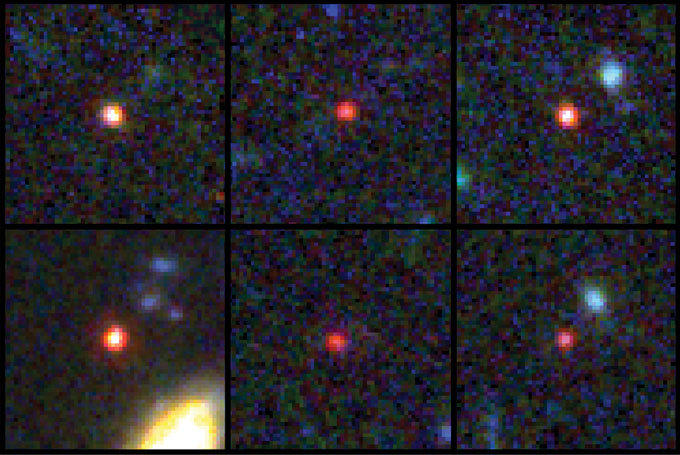

Second, a handful of those galaxies appeared to be monstrously massive. These all dated back to the first 700 million years of the universe. And they were up to 100 times as heavy as scientists thought possible back then. For that reason, these galaxies were dubbed “universe breakers.”

Our current understanding of how the universe grew up goes like this. First, dark matter collapsed into giant clumps known as halos. This happened within the first few hundred million years after the Big Bang. The halos’ gravity then pulled in normal matter. This eventually formed stars and galaxies.

This would have taken time. Matter would have clumped together slowly, eventually building up larger and larger galaxies. If true, the jumbo galaxies that JWST spied so soon after the Big Bang shouldn’t be possible.

What’s more, the current story of the universe doesn’t predict nearly enough dark matter halos in the early universe as would be needed to build the many big galaxies that JWST saw.

In that light, things look pretty dire for scientists’ current theory of how the universe evolved.

But Muñoz and his colleagues think it’s too soon to tear up our current picture of how our universe evolved. Perhaps, they say, scientists simply need to be more careful as they interpret data from JWST.

Hubble weighs in

Muñoz’s group decided to check JWST’s results using data from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope. Hubble is older. And its “eyesight” isn’t as good. So it can’t see quite as far back in time as JWST can. But both instruments can capture light from galaxies in one era. That era spans roughly 450 million to 750 million years after the Big Bang. JWST views those galaxies in infrared light. Hubble sees their ultraviolet light.

If there really were 10 times more dark matter structures in the early universe than we thought, “there would be 10 times more galaxies in James Webb” images, Muñoz says. And, he adds, “there would also be 10 times more galaxies in Hubble [data].”

But that’s not what the Hubble data show.

The team tallied how many galaxies Hubble saw across a wide brightness range. Then, they tried adding more dark matter halos to their model of the early universe. If they added enough halos to match the JWST data, their model could not match the Hubble data.

So … which telescope should we trust?

JWST is the more powerful of the two. It can simply see more galaxies than Hubble can at a given distance. But Hubble has been staring at the universe for much longer, Muñoz notes. JWST started collecting data only in 2022. Hubble has been looking out at the cosmos since 1990. This means that right now, Hubble’s data more reliably reflect what’s out there, Muñoz argues.

For that reason, the researchers suggest looking at other explanations for JWST’s odd galaxies — ones that don’t involve rewriting the history of the universe with new physics.

What’s going on?

Scientists thought the galaxies in JWST’s images were super massive. They just looked so super bright. But perhaps there’s some other reason for their brightness.

Conditions in the early universe might have been different than later on. This may have allowed gas and dust to turn into stars much more efficiently than had been thought. Maybe such speedy star formation created the weirdly bright objects JWST sees.

Star formation also might have been more episodic. That is, there may have been quiet periods with little star formation, followed by periods full of fast star formation. The stars from each burst of star formation would all be close to the same age. So they’d all die as explosive supernovas around the same time, one after another. In that case, JWST might simply be capturing some galaxies at these moments of intense brightness.

It’s also possible that some of the light that JWST sees in these early galaxies comes from their centers. There, supermassive black holes could be gorging on the matter around them. That frenzied feast would throw off a lot of light. And that, overall, could make a galaxy look super bright.

Other researchers are impressed by what Muñoz’s team found. “It’s very clever to look at the overlap region [between Hubble and JWST],” says Priyamvada Natarajan. She’s a theoretical astrophysicist at Yale University.

But Erica Nelson points out that the cosmos isn’t entirely safe yet. Nelson is an astrophysicist at the University of Colorado Boulder. She was part of the team that first identified the “universe breakers.” If any of these objects really is as massive as it looks, she says, “it is a problem.”

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores