With measles outbreaks in 49 countries, should you worry?

Not if you’re vaccinated, experts say. Childhood shots offer lifelong protection

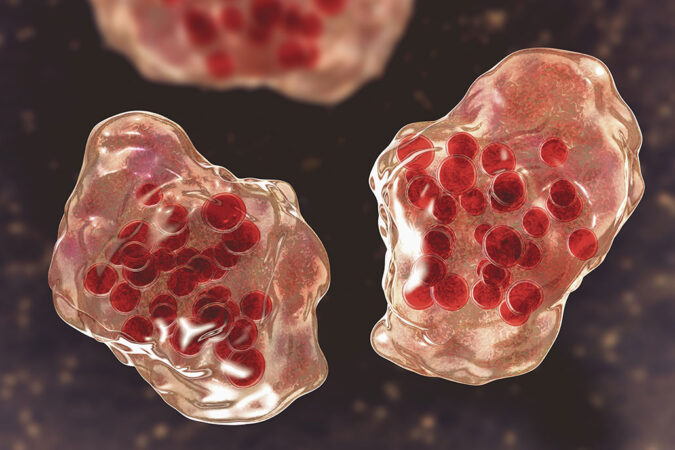

Along with experiencing flu-like symptoms, people with measles develop a distinctive rash that covers the body.

Povorozniuk Liudmyla/iStock/Getty Images

Measles outbreaks have been ringing alarm bells in the United States and elsewhere. What is this disease and how concerned do you need to be? Science News Explores talked with experts to find out.

“Measles is one of the most contagious diseases around,” says Jasmine Reed. She’s a spokeswoman for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). That’s in Atlanta, Ga. Much like the flu, measles is caused by a virus that infects the nose and throat.

Almost 130 cases of measles emerged in the first three and a half months of 2024 across 20 U.S. states, CDC reports. That may not sound like much, but it’s more than double the number of U.S. cases in all of 2023.

A potentially lethal disease, measles was eliminated from the United States 24 years ago. “Eliminated” means it no longer exists here on its own. Cases are almost always due to travelers bringing the virus in from outside the country.

Between September 2023 and February 2024, 10 other nations reported huge measles outbreaks. An outbreak involves three or more related cases. In each of these nations, mostly in the developing world, those outbreaks totaled at least 4,300 cases. (In Kazakhstan, for instance, there were 27,280.) But those countries are far from the only places affected. By late March, CDC reported large measles outbreaks in 49 countries.

Make no mistake, measles is a serious disease. Worldwide, it kills more than 100,000 people a year.

The measles virus can live for up to two hours in the air, Reed says. And being super contagious, she notes, “if one person has [measles], up to 90 percent of the people close to that person … will also become infected.” That’s true unless they had already been infected or gotten a shot to guard against it.

Someone may have a headache, fever or congestion and think they have the flu. But that’s how measles starts, too, notes Carla Garcia Carreno. She’s a pediatrician at Children’s Health in Plano, Texas. Her specialty is treating infectious diseases.

Three to five days after someone is infected, a tell-tale rash will usually emerge. It typically starts on the face and spreads down to the body, arms and legs. This tends to be when people know they have measles. But “even before people develop this characteristic rash, they are still contagious,” Garcia Carreno notes.

Measles leaves people feeling pretty sick for a couple of weeks. But for some, the disease can be much more serious. Very young children and those with a weak immune system can develop bad complications. For instance, measles can cause pneumonia, Garcia Carreno says. It “can also cause some brain inflammation,” she adds.

Why are we seeing cases now?

Measles is much more common outside of industrialized countries. People who are not vaccinated, notes Megan Jehn, “can become infected with measles while they are traveling” and bring it home. Jehn works at Arizona State University in Tempe. As an epidemiologist, she studies how diseases spread.

Infected travelers can pass the virus to people who are vulnerable. That includes those who have not been vaccinated or who have immune systems that don’t work well.

More people are vulnerable to measles than before the COVID-19 pandemic. Why? Worried about catching COVID, many parents skipped doctor’s appointments for their kids, Jehn says. Many children then fell behind in getting important vaccines. Kids typically get these shots by age five.

It’s like a forest fire, Jehn explains. Think of unvaccinated people as the fuel for a fire. “The initial spark is typically a traveler bringing measles [home]. If there is a lot of fuel for the fire, it will continue to burn. If there is no fuel for the fire, it will quickly become extinguished.” After all, germs can only take hold in vulnerable people.

All three experts emphasized the importance of getting vaccinated.

The U.S. measles vaccination program started in 1963. Before that, an estimated 3 million to 4 million people got measles each year, says Reed. In all of 2023, there were just 58 reported cases.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

Measles vaccines are safe, says Garcia Carreno. Those early childhood shots protect most people from measles for the rest of their lives.

And here’s good news for those who haven’t gotten the shot but become exposed to someone with measles: The vaccine can stop an infection even if someone gets it after they’ve inhaled the virus. “That’s how powerful the vaccine is,” Garcia Carreno says. The key is to get the vaccine within three days of being exposed to the measles germ.

“We are hearing a lot about measles in the news right now,” Jehn says. More kids need to get vaccinated, she says. If not, “we will be seeing more and more of these localized outbreaks pop up.”