How to help transgender and nonbinary teens bloom during puberty

Simple medical care helps these youth develop an adult body to match their gender

Hundreds of thousands of U.S. teens are transgender or nonbinary. Puberty for them may look different than for their cisgender peers. With support and treatment, they can develop an adult body to match their gender and thrive.

Halfpoint Images/Moment/Getty Royalty Free

When Mary started puberty, she went to the doctor. She was 12, and it was the first visit for this transgender girl to an endocrinologist. These doctors specialize in the function of hormones and the glands that secrete them. They discussed treatments that would help her body and gender match after puberty.

Mary is not her real name, but one selected to protect her privacy.

Puberty is when a child’s body begins changing into an adult. Their bodies make more of the hormones that will allow a girl to morph into a woman and a boy into a man. And that’s fine for most cisgender kids, whose gender matches the sex they were assigned at birth. For these individuals, usually no medical care is needed.

But around 1.4 percent of U.S. teens are transgender. Their gender differs from the sex they had been assigned at birth. Another 2.5 percent are nonbinary, meaning their gender is not exclusively male or female. (It could be both, in between male and female or neither. Some but not all nonbinary people identify as transgender.)

Having a body that doesn’t match one’s gender can cause extreme distress and mental-health problems. As a result, many of these individuals may need medical treatment to help their bodies begin to match their gender.

Such treatment typically starts at the onset of puberty. This tends to be around age 9 to 12, when armpit or pubic hair starts to grow. Treatments to guide puberty have existed for decades and are also used in cisgender kids who need them. These include medicine to pause puberty and hormones to restart it. For some, treatment also can include surgery, usually after age 18, to shape someone’s adult body.

A pause button for puberty

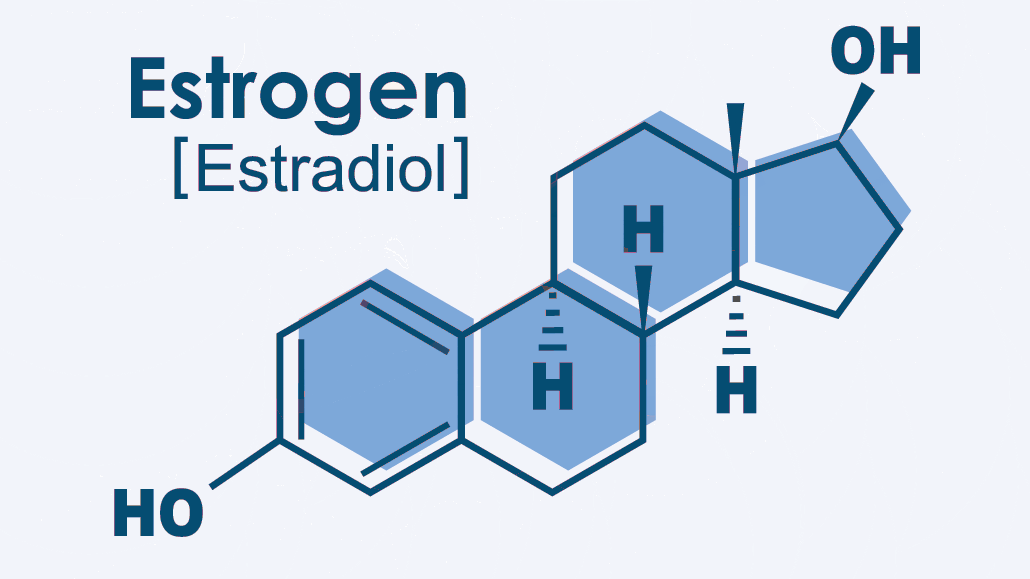

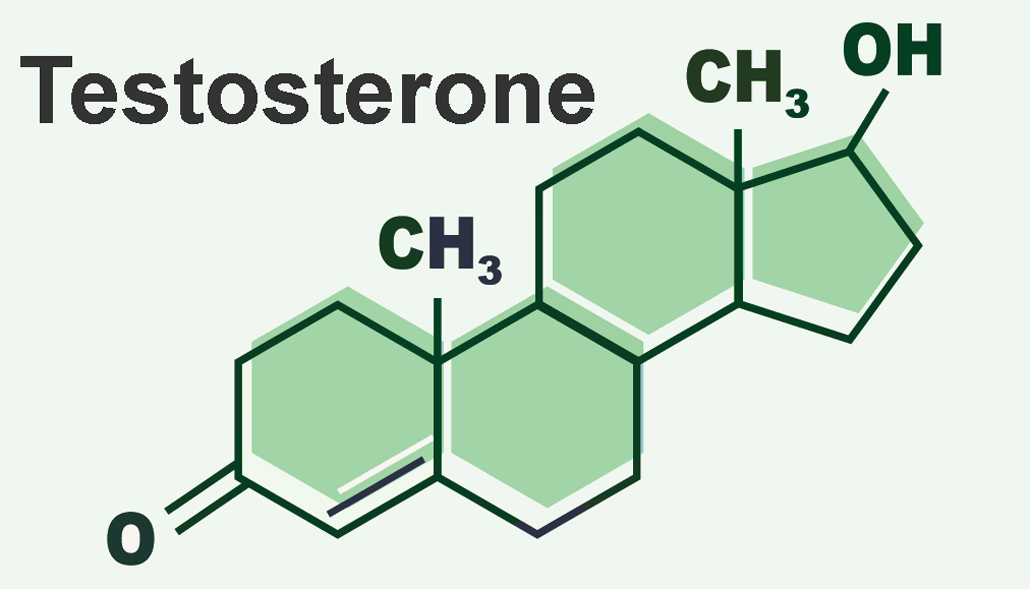

The main hormones that guide puberty are estrogen and testosterone. Both have many jobs and act as chemical messengers to carry out those tasks. Estrogen plays a role in keeping the bones, brain, heart and liver healthy. Testosterone also helps keep bones and muscles healthy. It also affects mood and energy levels.

During puberty, these hormones take on additional roles. They tell the body to start producing what are called secondary sex characteristics. Those include a beard or breasts.

People designated female at birth typically produce more estrogen; those designated male at birth usually make more testosterone. But anyone with testes or ovaries makes both hormones, notes Douglas Austin. How much of each they make will vary over their lifetimes.

Austin is an endocrinologist at the Fertility Center in Eugene, Ore. One aspect of his work is to manage those hormones that determine how our bodies develop. He works with transgender kids and their families. He helps adjust hormone levels in these kids during puberty to guide their bodies’ development.

For many of these young people, puberty blockers are the first step, says Austin. If given soon after puberty starts, these blockers act like a pause button. (This medication also may be given to cisgender kids who begin puberty too early, he says.)

When puberty starts, a part of the brain called the hypothalamus sends a message to its neighbor, the pituitary gland. It instructs the bean-sized gland to message the body’s testes or ovaries. Spit out more hormones — testosterone or estrogen — it says. Blockers get in the way of this, says Austin. They stop puberty’s call to produce more such hormones. That also stops the development of body changes such as breasts or facial hair.

Mary knew she was transgender from a young age, about 3 or 4 years old. But some transgender people don’t realize it until later, often around puberty. That’s one reason blockers can be so helpful. They give teens more time to explore their identity before their bodies undergo permanent changes. Mary’s doctor prescribed a blocker called Lupron. This stopped her body from making extra testosterone.

‘Bio-identical’ hormone therapy

Most youth on blockers go on to take hormones that will restart their puberty. Depending on the person, this may be after a few months or even a few years. Mary’s hormone therapy started with estrogen patches twice a week for two years. She likened it to “putting a sticker on my hips.” Now, she takes pills. As her estrogen levels increased, her body began looking more like a typical woman’s body.

After taking estrogen, Mary says she feels better about her body and herself.

This is called “bio-identical” hormone therapy, explains Austin. The molecules in the patches and pills are identical to the hormones our bodies make. Transgender boys take testosterone. Transgender girls take estradiol — the strongest of four estrogens produced in the body.

Nonbinary kids may want their adult body to look between what’s considered male or female. Achieving this is very much trial and error, says Austin. He uses hormones to sculpt their bodies to be “less male or less female.” The end goal is an adult body that feels right for the individual.

Gender-affirming surgery

Some transgender and nonbinary teens may choose to have gender-affirming surgery. Trans males who developed breasts may choose to remove this tissue and sculpt their chests to look more typically male. This is referred to as top surgery. Other surgeries can reconstruct genitals. These are more complicated, says Austin, and the healing process is harder, too. That’s one reason people have to wait until they are at least 18 years old for this type of surgery.

Puberty-related surgeries are not only for trans and nonbinary people. Around 4 percent of cisgender boys aged 10 to 19 may grow breast tissue during puberty. Some later have surgery to remove the unwanted tissue.

Austin starts working with new patients years before any surgery may occur. Still, he talks about it on day one. This may feel scary for the parents, he says. But it’s important for kids to know their options and to think broadly about their future. Another consideration: Will they want to save sperm or eggs to have biological children later on? After surgery, they learn, this may not be possible.

Not all trans and nonbinary people want surgery, adds Tess Kilwein. She’s a psychologist in Nashville, Tenn. She works with trans and nonbinary young people across the country through her online practice. Some are satisfied with a social transition, which often includes changing their clothes, hair and pronouns. Others may choose only hormone therapy.

Now 15 years old, Mary does plan to have surgery. She’s excited, but also nervous. She looks forward to the day she can feel comfortable with her shape and wearing any type of clothes.

Life-saving hormones

Gender-affirming care saves lives, says Kilwein. Trans and nonbinary youth face a far higher risk of depression, eating disorders and suicidal thoughts than cisgender kids, she notes. But research overwhelmingly shows that gender-affirming care improves people’s mental health, quality of life and body image.

In 2023, researchers reviewed nearly 50 studies on hormone therapy and mental health in transgender people. In all, their data came from more than 40,000 participants. Those receiving hormone therapy reported less depression and fewer symptoms of anxiety. Overall, these people also felt more positive about their lives. Blockers, too, showed mental-health benefits in trans youth.

Some people may be concerned about possible physical impacts of blockers and hormone treatments. Puberty blockers are widely used and considered safe, says Austin. Most of their effects are reversible.

But two effects can last into adulthood.

One is height. Puberty kicks off a growth spurt that ends at someone’s adult height. If puberty is delayed, a person will keep growing, they just won’t get the rapid growth spurt. If used too long, someone may grow extra tall. This can be an issue for trans females who don’t want to be taller than most women, Austin says. “We have to time the transition properly to manage height expectations.”

Bone density is the other consideration. Hormones released during puberty strengthen bones. Blockers pause this important development.

When someone stops blockers or starts taking hormones, their bone density will again increase normally. There is a chance someone could end up with weaker bones, Austin says. But this should only happen if they took blockers and had their gonads (testes or ovaries) removed without receiving other hormones. That’s not likely to be recommended.

Hormone therapies have been studied for effects on heart and bone health. For example, some types of estrogen may increase the risk of stroke or blood clots. And in some studies, trans women had higher risk of heart attack than cisgender women. But their risks were the same as for cisgender men. In one review of 53 different studies of transgender people, hormone therapy didn’t consistently raise the risk of heart or bone problems.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

Threats to health care for trans and nonbinary kids

Mary lives in Oregon. There, her healthcare rights are protected. But that’s not true everywhere. As of 2024, almost half of U.S. states have laws restricting or prohibiting this care. Denying kids the option to grow into an adult body that matches their gender can harm their health.

Many lack access to the care they want. In one 2022 survey of more than 11,000 trans and nonbinary youth, half said they would like to use gender-affirming hormone therapy but were not. More than one in three were not interested in it. Just 14 percent were receiving such care.

“I wish people knew how much of a mental toll it takes [to be transgender], and how harmful it can be if you don’t get treatment,” says Mary. But treatment won’t solve everything, she adds.

Gender-affirming care isn’t a rigid type of medicine, says Austin. For youth, it’s a discussion on how to get from the early stages of puberty into the right adult body for them, then finding the treatment to make that happen.

And this process calls into question people’s prejudices around gender. For many parents, it’s the first time they’ve had to think about what gender means, he says.

Mary’s mother, too, found the process hard at first. She didn’t know how to talk about her daughter’s gender and felt the situation was a failure of her parenting. Now, she sees Mary’s gender as a gift. It’s helped their family become more flexible and accepting. Not just for transgender people, she says, but in all parts of their lives.

Suicide was the third leading cause of death among U.S. teens ages 15-19 in 2021. If you or someone you know is suffering from suicidal thoughts, please seek help. In the United States, you can reach the Suicide Crisis Lifeline 24/7 by calling or texting 988. Please do not suffer in silence.