Holey basketballs! 3-D printing could be a game-changer

An ‘airless’ design makes Wilson’s new basketball quieter and puncture-proof

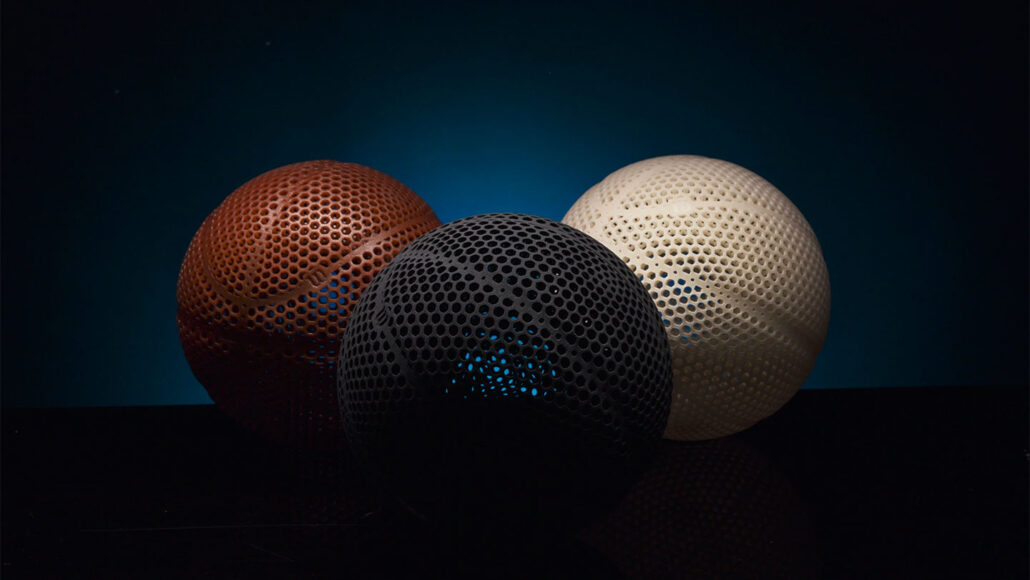

Not your parents’ basketball, this limited-edition 3-D printed model, released earlier this year by Wilson, comes in three colors. It’s billed as nearly silent and deflation-free. It should play like a normal ball. But it would take big bucks to try it out.

Wilson Sporting Goods

By Sarah Wells

Thump, thump, thump — swoosh! Basketballs have been dribbled across courts and shot through the air for nearly 150 years. In all that time, the look and feel of those balls has remained almost the same. But that could soon change.

Throughout history, these balls have been made of eight or 10 panels of either leather or a rubber composite. Pressurized air inside gives the ball its bounce. But Wilson Sporting Goods — the company that makes the National Basketball Association’s official game balls — has created a new type of ball. It uses no pressurized air. In fact, this ball is designed for air to flow through it. That means that it won’t puncture and deflate like an ordinary basketball.

Kind of like a honeycomb, its surface is a lattice of small, hexagonal holes. This complex shape is created through 3-D printing. It’s made from an elastic polymer. The end product is a ball with roughly the same weight as a standard basketball.

This Airless Gen 1 is the brainchild of Nadine Lippa. She’s Wilson’s manager of basketball R&D, based in Schiller Park, Ill. (R&D stands for research and development.) The new ball is “designed to be used without an air pump or needle,” she says. “Players can just pick it up and play with no preparation.” Lippa holds a PhD in sports and high-performance materials.

With all those holes, the ball looks totally different than a typical basketball. It feels different, too, Lippa adds, “because it’s made from a unique, highly elastic material.”

Though it’s still being tested, Lippa expects this ball will likely prove to be more sustainable — “greener” — than traditional basketballs, too. “We can print [these balls] on demand, which means we shouldn’t have excess product in certain colors or designs,” she notes. “[And] this ball has essentially one component with one supply chain [that] can be made locally.” That should reduce the carbon footprint of making and shipping them.

But the most dramatic feature of this limited-edition ball is its cost. At $2,500, it’s more than 100 times more expensive than Wilson’s cheapest ball. That leaves players to decide: Is it worth it?

The science of bounce

A traditional basketball loses its bounce over time. Dribble a new or newly inflated basketball and it immediately springs back from the ground. The bounce of an old or somewhat deflated ball, however, may not return high enough to reach your hand.

The bounce comes from the air pressure inside these balls. As some air starts to seep out — and over time, some will — that pressure will fall. Now, no matter how much force you apply, the ball cannot bounce as high.

The new basketball’s 3-D printed polymer lattice helps solve that problem, says Monique McClain. She’s a mechanical engineer at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind., who works on 3-D printed materials. The bounce in Airless Gen 1, she says, comes in part from the ball’s structure.

“The advantage of a lattice is that it can deform,” she says. “When you’re deforming the lattice, there’s [a] storage of energy — kind of like springs.” Later, the release of that energy allows the ball to bounce back up.

Based on how the lattice is designed, this bounce could be very large or very small.

Another benefit to the new ball’s design is that its bounce is much quieter than that of a traditional basketball. Online reviews describe a soft “whoosh” as air flows through the ball. This feature could be beneficial for players who don’t want to disturb the neighbors as they dribble in their driveway at night. Reviews also note that the ball feels very different to the hand, even while bouncing identically to a pressurized basketball.

The material used to build its lattice also plays a big role in the new ball’s bounce and durability. Wilson has not revealed exactly what this ball is made from, but McClain says it would need to be a mixture of something “squishy and bouncy.” Nike may be using a similar product in the high-performance, 3-D printed soles on some of its sneakers, McClain says.

Slam dunk or air(less) ball

Even though the Airless Gen 1 is innovative, it may not outperform a traditional ball.

“Players … [have] built a certain connection with exactly how much force to put through the ball to be able to make a shot,” says Patrick Cavanaugh. He’s a research engineer at Purdue University’s Ray Ewry Sports Engineering Center. All those holes may change the new ball’s wind resistance, he says. With different aerodynamics, “shooting that ball is going to result in a different flight path.” And that, he says, “is going to require [someone] to relearn how to make that shot.”

Players might also feel a difference in how they grip the ball, says McClain.

Even qualities that don’t impact the ball’s performance, like a quiet bounce, could be an issue. Materials engineer Jan-Anders Mansson directs Purdue’s Ewry Center. Imagine hitting a tennis ball without the thwack of a racket, he says, or a home run with no crack of the bat. It would be a big adjustment for players to dribble a virtually silent basketball down the court.

“Human perception is enormously sensitive,” Mansson says. “And sound is extremely important in sports.”

This could also impact fans’ experience, Cavanaugh adds. The sound of squeaking shoes and the thud of the bouncing ball help signal an exciting game.

The future of basketball

Even though this design has some kinks to work out, Mansson says he “totally loves the concept” of an airless ball. “It’s innovative and it’s opened up a whole new area of possibilities.” For example, imagine embedding smart sensors in this ball. One day, they might monitor stats, like acceleration, he says.

As for Lippa, she’s excited for what this ball can teach young players about the world of sports technology.

“Many people don’t realize how much engineering goes into sports products,” Lippa says. “Revealing the exciting technical aspects of sports engineering can be a great inspiration to go into STEAM fields.” (STEAM refers to science, technology, engineering, arts and math.) In fact, she says, “We are excited to see how the next generation will use this budding technology to solve problems and have fun.”

Most people don’t have thousands of dollars for a designer ball. Makers have already begun 3-D printing their own attempts. But so far, none perform like the real thing — which took five years to develop. It also went through rigorous testing at Wilson’s NBA test facility in Ada, Ohio.